An examination of our first alumni President’s time in offce.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

An examination of our first alumni President’s time in offce.

On January 20, 2009, Barack Obama ’83 (his graduation coincided with my first year teaching at Columbia) became the 44th President of the United States and the nation’s first black President. He will leave office in January 2017 having served two full terms. While Obama’s election was an historic event, filled with high hopes, his accomplishments and legacy are controversial and will be debated for years.

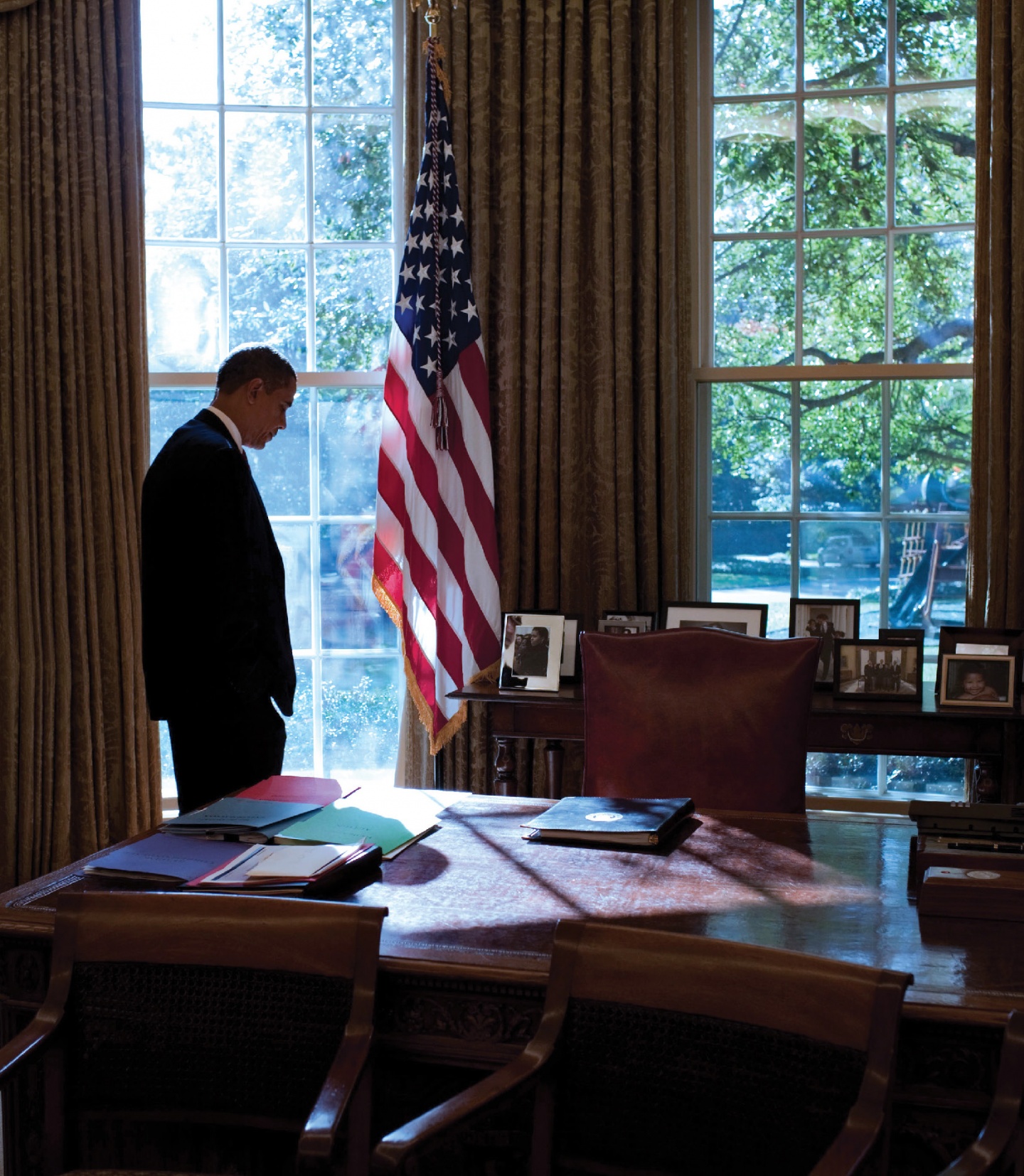

President Barack Obama ’83 walks to his desk in between meetings in the Oval Office, October 20, 2009.

Pete Souza

When Democratic Party candidate Obama defeated Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) in 2008, George W. Bush’s presidency was ending at a low point, directly related to both the military quagmire that occurred after the United States’ invasion of Iraq in 2003 and to the financial crisis at that time. The nation was entering into a Great Recession. Dealing with this posed a great challenge, but expectations were high — indeed too high. Working in Obama’s favor was his strong electoral showing: 53 percent to 46 percent in the popular vote and a 365–173 rout in the Electoral College. The Democrats won a large majority in the House of Representatives and for a brief period in 2009 had a 60–40 libuster-proof Senate majority. Working against Obama was an enormous (and still growing) partisan divide among Democratic Party and Republican Party leaders and voters. Widely written about by political scientists (myself included), this ideologically-driven partisan divide emerged in the 1970s and took off by the 1990s; Bush — who aspired to be a “uniter” not a “divider” — had hoped to end it but failed.

It’s important to consider the history here. The two major parties had been ideologically mixed after being realigned in the 1930s. Southern Democrats who were conservative on racial and labor issues countered the northern liberal wing of the party; moderate Republicans who were liberal on civil rights and other issues countered their party’s economic conservatism. The balance slowly unraveled with the ascendancy of northern Democrats in tandem with the Civil Rights movement, which led the Democrats, spurred by President Lyndon Johnson, to become the more liberal party on racial issues with the passage of landmark civil rights and voting rights legislation in 1964 and 1965. Over time, southern conservative Democrats left the party and the Republicans began to pick them up as part of Republican President Richard Nixon’s “southern strategy” in 1968. As new issues arose, intra-party competition led the parties to divide ideologically, with Democrats as liberals and Republicans as conservatives on economic and regulatory issues as well as on individual rights and liberties, with moderates slowly disappearing from both parties, especially the GOP.

By 2008, virtually every major issue divided the parties. Political emotions were running high, and there was a widening rift in national security and foreign policy as the Democrats and Republicans came to differ on the use of diplomacy versus the unilateral use of military force. Adding to the conflict was the fact that with the 1980 Senate and 1994 House elections, the parties became evenly matched for control of all branches of government. This increased the stakes in national elections, and it explains why Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) said in October 2010, “The single most important thing we want to achieve is for President Obama to be a one-term president.”

McConnell’s statement summarizes the opposition that Obama faced in crafting policies to address the nation’s problems. Furthermore, partisan conflict affected how both political leaders and the public would perceive Obama’s accomplishments. The number and scope of the Obama administration’s actions and the changes that have occurred on Obama’s watch have been enormous by any reasonable metric applied to American Presidents. If these accomplishments were largely viewed as positive, as his Democratic Party supporters saw them, Obama would be considered one of the greatest American Presidents. If mainly negative, as Republicans viewed them, he would be one of the worst. A fair answer, however, is that the jury is still out how his overall actions will play out in the long term. This is disappointing to those who hoped that his presidency would be seen as an unequivocally bright period in American history.

Some of Obama’s least controversial domestic initiatives were punched through soon after he took office: the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, expanding the Children’s Health Insurance Program to cover more children in need; the elimination of restrictions on embryonic stem cell research; and the Hate Crimes Prevention Act, encompassing crimes related to gender, sexual orientation and disability. Obama also later filled two Supreme Court openings with women: Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor, the latter the first Latina Supreme Court justice.

Much more controversial was Obama’s health care reform. The Affordable Care Act was historic — on the order of the establishment of Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. The ACA expanded substantially the number of people insured by requiring everyone to have health insurance and helping to provide it. It imposed regulations to make medical coverage — with no limits due to preexisting conditions — available to all through the expansion of Medicaid (optional for states) and state or federal insurance exchanges, and provided subsidies to help individuals pay for insurance. Democrats hailed it as a landmark breakthrough. Republicans saw it as Big Government intrusion at its worst and as a policy that worsened the health care system. The ACA’s implementation has had problems, including some costs and providing sufficient insurance options to individuals not covered through their employers or Medicaid. The future of the ACA will depend on Obama’s successor, and there is some doubt at this writing that Donald Trump, the newly elected President, and the Republican Congress will immediately pass and sign legislation that will do away with “Obamacare.”

Disagreement has remained over the $787 billion Economic Stimulus Act, created to get the country out of the Great Recession. Unemployment benefits and payroll tax cuts were later extended. The national economy recovered — more jobs and economic growth, with low interest rates and low inflation — especially compared to other countries that adopted more austere measures. Democrats praised these actions but lamented that had added government spending not been thwarted by Republicans, economic growth and wages would have recovered further. Republicans criticized Obama for not cutting taxes and government regulations that could have enabled the market to produce a stronger and lasting recovery to benefit the middle class. The same debate ensued early in Obama’s second term, when the Democrats successfully opposed restoring tax cuts for the very wealthy.

Also highly controversial, and with open questions about the long-term impact, was Wall Street reform legislation (Dodd-Frank and the Consumer Protection Act) to reregulate the financial industry, and the administration’s actions to provide funds to recapitalize banks (which the government later recovered). Partisan critics disagree on whether this regulation or intervention was too little or too much — or even necessary.

And there was more disagreement: Exceeding the initiative taken by George W. Bush, the Obama administration injected more than $60 billion into the auto industry to save it from bankruptcy and succeeded in turning it around. Democrats praised this for sparing jobs and boosting manufacturing, while Republicans were less supportive of the level of government involvement.

Obama, Vice President Joe Biden and senior staff react in the Roosevelt Room of the White House as the House passes the health care reform bill, March 21, 2010.

Pete Souza

Republicans criticized Obama’s increases in government regulation, for example around issues of food quality and especially around actions that expanded wilderness and watershed protections. His administration aimed to double fuel economy standards for cars and trucks by 2025 and created restrictions on toxic pollution that led to the closing of the nation’s oldest and dirtiest coal-fired power plants and increased pressure to close coal mines. Republican leaders especially complained about the use of executive orders to impose new regulations.

The politics of international relations that Obama specialized in while a Columbia political science major changed dramatically after the end of the Cold War. His foreign and national security policies have led to heated debates that perhaps began when he was awarded the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize, not long after he took office, for his ongoing emphasis on diplomacy. He also created controversy by reaching out to the Muslim world, and with his concerns about nuclear proliferation and climate change.

Obama ended U.S. combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, which resulted in debate over the number of U.S. troops that should be left to provide assistance. A high point was when he successfully ordered the Navy Seals mission that found and killed Osama bin Laden in retaliation for the 9-11 terrorist attacks. But warfare in that region continued, and critics claim Obama’s policies created a power void that gave rise to ISIS terrorist groups and prolonged the civil war in Syria that has resulted in millions of refugees fleeing that country. Obama stood fast, emphasizing the need for a political solution in the region based on the American experience in Iraq and Afghanistan. He was severely criticized for not providing sufficient arms to the Syrian rebels whom the U.S. supported and not using U.S. air power to protect civilians in places where the Assad regime and its Russian allies attacked civilian targets and prevented humanitarian aid. The administration succeeded in helping topple — leading to the killing of — Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, but this produced conflict and instability in Libya, where U.S. Ambassador J. Christopher Stevens was later killed and where ISIS made inroads. At this writing, two months before Obama leaves office, his administration has continued assisting in the onslaught on ISIS in Iraq and Syria, providing support for the attacks on ISIS’ major strongholds in Mosul and Raqqa.

Equally — if not more — controversial was the agreement the administration reached on Iran’s nuclear program. There was vehement, and especially partisan, disagreement over the ending of tight and effective sanctions against Iran and the freeing of Iranian funds held by the U.S. The agreement, which was angrily opposed by Israel and other allies threatened by Iran, appears to have stopped Iran’s nuclear program in the short term, but long-term effects are uncertain.

Less controversial was the Obama administration’s effort toward the 2016 Paris Agreement on global climate change, which has been hailed as a breakthrough in international cooperation. The administration had also earlier achieved a new START treaty on nuclear arms with Russia.

Finally, the Obama administration’s diplomatic recognition of Cuba’s government is historic. Obama was criticized in Republican Party circles and by some Democrats for this action, but a majority of the public quickly supported it as did the international community, especially Latin American countries for whom this was long overdue and for whom the United States’ treatment of Cuba had hampered diplomatic relations.

There were other major developments during Obama’s time in office. Most noteworthy were the major advancements in gay rights: first the ending of the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy in the military, then the further legalization of gay marriage in the states, which led quickly to the Supreme Court ruling that legalized it nationally.

U.S. oil and natural gas production took off during the Obama years, making the country increasingly energy self-sufficient. The U.S. became a greater international energy producer, which contributed to the economic recovery and especially benefitted certain states. Consumers also benefitted greatly from a sharp drop in the price of gasoline. On the other hand, this development on the energy front led to further partisan debates about environmental protection regulation — including conflict over the use of hydraulic fracking, which had greatly expanded production.

Memorably, and painfully, ironic is that the expected progress during an Obama presidency toward a “post-racial” America did not occur. Rather, there was a return of racial conflict reminiscent of the 1960s, including violent protests after a number of shootings of blacks by police officers and subsequent killings of police. This amplified debates over racial profiling and “stop and frisk” policies. There were also new racial and ethnic-related tensions over immigration, the threat of radical Islamic terrorism and the U.S. taking in refugees from the Mideast. Racial resentment that had earlier divided the two parties resurfaced. Obama was criticized on both sides, by his opponents for the disruptions and for not adequately backing law enforcement, and by his supporters for not defending racial justice more directly and loudly. This partisan conflict may have had racial underpinnings as well, as suggested by continued Republican accusations that he was not born in the U.S. or that he was a Muslim, and in a stunning instance of political incivility early on when he was heckled (“You lie!”) by a Republican congressman during a major, nationally televised speech to a joint session of Congress.

Where does this leave us? What can we definitively say about Obama’s eight years in office? As to his place in history, it is too early to tell; for example, how health care reform and international agreements and conflicts play out remains to be seen. Where does he stand compared with other Presidents as they left office? We have some initial evidence from the President’s popularity ratings provided by Gallup and other opinion polls. By these measures Obama fares very well, an average of more than 50 percent approving his performance as President in the month before the 2016 election. This puts him at the same level as Ronald Reagan during the same month, and higher than all Presidents since Harry Truman except for Dwight Eisenhower and Bill Clinton, whose approval was five points or more greater than Obama’s.

Given the controversy over his accomplishments, we can understand why Obama’s approval rating is not higher — and why it might have been much lower. He has expressed regret that he did not do more to lessen the partisan conflict and that his administration had not thought through the consequences of U.S. action in Libya. But why is his rating as high as it is? Is it that the economy has clearly improved since he took office? That certainly has not held him down, but there are several other relevant factors. One is that due to the partisan divide, he gets very high ratings from fellow Democrats. More important, U.S. casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan were greatly reduced, to near zero, whereas ongoing casualties in these conflicts had adversely affected evaluations of George W. Bush as he neared the end of his presidency (his rating was 20 points lower than Obama’s).

The legacy of Columbia College’s first alumnus/a to become President of the United States will largely depend on forces beyond his control.

Another reason Obama rates highly is that his administration has been strikingly free of scandals. His inspirational personal qualities still bolster his support, especially when compared with the 2016 major party presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Trump, who had record-high unfavorable ratings for candidates in what was the most conflict-ridden and personal presidential campaign of modern times. These qualities are further bolstered by First Lady Michelle Obama and their daughters. The Obamas have strengthened their connection to the American people through their concern for veterans and military families, and Michelle Obama’s initiatives on education and childhood obesity. In addition to the Obama administration’s double-digit increase in the Department of Veterans’ Affairs budget, new GI Bill provisions for substantial tuition assistance across the next decade and multiple tax credits encouraging businesses to hire veterans, Michelle Obama and Vice President Joe Biden’s wife, Jill Biden Ph.D., launched the national Joint Forces “initiative to mobilize all sectors of society to give our service members and families the opportunities and support they have earned.”

There is a strong Columbia connection here. The atmosphere and dialogue for this began (as I was reminded by civil-military expert Army Lt. Col. Jason Dempsey GSAS’08 (Ret.), a former White House Fellow who worked with Michelle Obama on military family issues) when Obama and McCain participated in an armed services forum at Columbia during the 2008 election campaign. Columbia itself, only fittingly, has since become a national leader in its outreach and programs for veterans.

In the end, the legacy of Columbia College’s first alumnus/a to become President of the United States will largely depend on forces beyond his control: his being followed by someone with radically different ideas, as certainly appears to be the case with Trump, and the Republican Party’s control of both the Senate and House of Representatives. Trump and the Republicans are expected to seek to void much of what Obama has attempted to achieve. Time is likely to tell us soon about what can be undone easily by executive orders and by legislation that is at the ready, particularly in the case of the ACA. The consequences of Obama’s other major accomplishments that Trump has threatened, notably the landmark global climate and Iran nuclear agreements, will be known later.

Robert Y. Shapiro is the Wallace S. Sayre Professor of Government in the Department of Political Science and specializes in American politics. He received a Columbia Distinguished Faculty Award in 2012.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu