Publisher Louis Rossetto ’71 kicks off a new book venture — with an old-fashioned twist.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Publisher Louis Rossetto ’71 kicks off a new book venture — with an old-fashioned twist.

NORMAN POSSELT (2)

You don’t need a business degree to know that printing a novel on an antique press and selling it on Kickstarter is not a sure path to riches. But Louis Rossetto ’71, BUS’73 has never been led astray by his irrepressible optimism. In 1993 he launched Wired, the world’s first consumer tech magazine, with $900,000 and no conventional backers. He sold its properties five years later for $390 million. Now he’s decided to publish his second novel, Change Is Good, in much the same spirit: as a wild grassroots experiment.

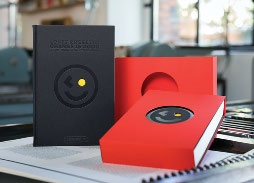

This time, Rossetto enlisted his friend Erik Spiekermann, a German design guru turned inventor, to create more of a proof of concept than a conventional book, a product that melds digital tools with centuries-old technology (call it Letterpress 2.0). Rossetto took their idea straight to the people and, again, found his optimism vindicated — 18 times over. In just one month, the Change Is Good project barreled past a $10,000 Kickstarter goal to raise more than $180,000, enough for a healthy print run of 2,500 copies.

Rossetto founded Wired in 1993; its ink-saturated design was an inspiration for Change Is Good.

On a crisp day in October, after visiting his daughter, Zoe Rossetto Metcalfe ’21, Rossetto sat on the Low Steps to recount his latest career twist. In 1974, the newly minted M.B.A. published Take-Over, a thriller about a fictional Nixon-era government coup, before moving to Amsterdam and working on trade magazines. A quarter of a century later, the sale of Wired made Rossetto an unemployed millionaire. After a few years raising Zoe and his son, Orson, with his life partner (and Wired co-founder), Jane Metcalfe, Rossetto started to think of telling a story closer to home: the San Francisco tech scene in 1998, gripped by the IPO fever that turned would-be revolutionaries into wannabe billionaires.

Change Is Good was born a dozen years ago as a detailed movie treatment, complete with illustrations and casting ideas. Rossetto bought two digital cameras and started planning the movie himself. “But then I ended up being the CEO of a chocolate company,” he says, “and there went seven years.” [Editor’s note: See “Louis Rossetto ’71 Goes from Wired to Chocolate,” Summer 2013.] An early investment in the luxury chocolatier TCHO had quickly turned into a full-time startup job. By the time he handed over the reins, Rossetto felt less keen on producing a movie. “Serial television had become the center of creativity,” he says, “but I can’t do television because I’m a nobody in that sector. How do I get past the gatekeepers?”

NORMAN POSSELT

Since Wired had rapidly expanded from print to the web and even TV, why not launch Change Is Good the same way — text first, other media later? During the couple of years it took to turn his movie treatment into a proper novel, Rossetto queried one literary agent, who gave him valuable advice. But then he started talking with his old friend Spiekermann, who was in the middle of his own late career twist. Spiekermann had founded Meta Design, Germany’s largest international branding firm, with a specialty in typeface design. But in his youth, he’d been obsessed with a much older form of printing. In 2014, after retiring from marketing, Spiekermann went back to his first love, founding the Berlin letterpress workshop p98a.

Anyone who’s been invited to a wedding in the past decade will recognize the vogue for letterpress printing. Not unlike artisanal chocolate, the process caters to consumers nostalgic for old-fashioned, small-batch, high-quality products. Typically, letterpress uses a 1950s-era machine — imagine a giant steampunk office printer that’s just eaten an old typewriter — to physically impress letters and shapes into paper, creating borders that seem to pop out of the surface (but actually pop in). These antique presses are too cumbersome to produce much more than cards and posters and the occasional pricey art book. But Spiekermann had spent the last few years incorporating new technology with the aim of making beautiful and readable books cheaply enough to build a viable publishing business. His plates are made of lightweight polymer instead of metal, carved by lasers that translate digital fonts into physical type.

Spiekermann was still perfecting his Letterpress 2.0 process in January 2017 when Rossetto approached him about Change Is Good. Together they hatched a plan to use the novel as a test case, and to use Kickstarter to drum up both funds and publicity. “My intention was never really to make this a publishing hit,” says Rossetto, “and even if I did, the best way to do it is to go direct.”

Rossetto partnered with German designer Erik Spiekermann to create an artisanal look for his new book.

NORMAN POSSELT

Spiekermann estimates that every copy of Change Is Good costs just over $40 to produce — half of that spent on its die-cut, foil-stamped cover and slipcase. The books sold on Kickstarter for up to $98 apiece. It’s easy to see where the money goes: Though the text between Change’s fancy covers isn’t illustrated or formatted much differently from your average book, it looks and feels sharper, more permanent. The gap in quality between conventional offset printing and letterpress is “the difference between water and oil, Wonder Bread and whole grain,” says Spiekermann. “Our ink is really thick and black. The register is incredible.”

Six-hundred-year-old technology might seem like an odd vehicle for a history of the digital revolution. But Rossetto has always been obsessed with physical objects, or “going from bits to atoms,” as he puts it. The influential look of the old Wired — ink-saturated and almost phosphorescent — was crafted on a rare six-color press. “We got more ink on the paper and subconsciously that comes across,” he says. Today, “there are things that still deserve to be on paper — but if you go to paper, you should try to do the best you can.”

Change Is Good’s story kicks off at a massive and decadent San Francisco tech party in 1998, on the eve of the IPO of a hot search engine called Gnuhere. (Google was incorporated the same year.) Following six characters — including Gnuhere’s hacktivist founder, his artist girlfriend, a banker about to take them public and the party’s DJ-slash-Ecstasy dealer — the novel chronicles a generation on the verge of selling out. “The tech industry itself plateaued a long time ago,” Rossetto says, but its idealism is still alive — at least in him. The novel’s tone is more nostalgic than ironic and, ultimately, as stubbornly sunny as its author. “I’m trying to reconnect people to the sense of wonder and optimism that was abroad at the time,” he says. “These were pioneers, the young people who went out into the unknown and came back with all the things that shaped the present.”

Rossetto agrees we’ve come a long way from the days when it looked like technology would make the world kinder and more democratic, “but I don’t think you can be an entrepreneur and not be an optimist,” he adds. His hopes for the novel itself are a little more down to earth. “I’m just happy to break even,” he says. “And if there’s money left over, we’ll have a party.”

Boris Kachka ’97, JRN’98 is a contributing editor to New York magazine. He has also written for The New York Times, GQ, Condé Nast Traveler, Elle and other publications, and is the author of Hothouse: The Art of Survival and the Survival of Art at America’s Most Celebrated Publishing House. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu