Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Bridging Differences Through the Bard

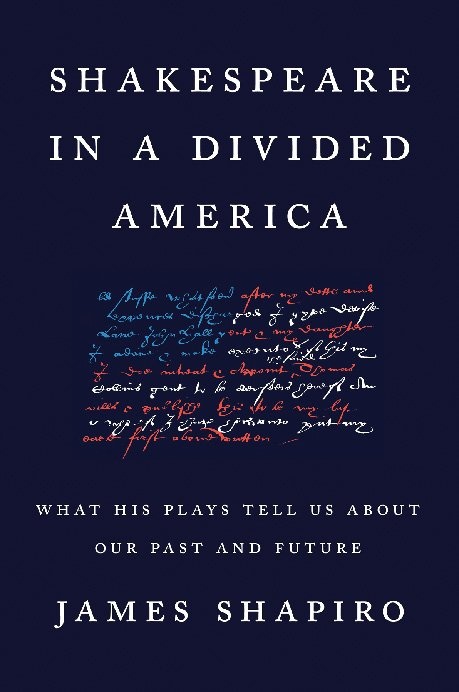

In Shakespeare in a Divided America: What His Plays Tell Us About Our Past and Future (Penguin Press, $27), Shapiro, the Larry Miller Professor of English and Comparative Literature at the College and a renowned Shakespeare scholar, looks at the ways in which people reveal themselves through interactions with Shakespeare’s work. Shapiro writes, “his plays are rare common ground.”

We all study Shakespeare at some point; the majority of American junior high and high schools expose students to Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth and Hamlet. Shapiro believes that Shakespeare’s work can help make sense of controversial issues in our nation’s history. “It’s frightening how much darkness, how much prejudice, how much resentment has inadvertently been revealed through America’s engagement with Shakespeare,” he says.

The book draws cultural through lines to landmark Shakespeare productions, films and musicals that have featured hot-button topics such as immigration (The Tempest), interracial marriage (Othello), class warfare (Macbeth), domestic violence (The Taming of the Shrew), same-sex marriage (As You Like It), adultery (Hamlet), gender identity (Twelfth Night) and, in numerous instances, the Other.

“One of the things I’ve explored in Shakespeare’s comedies is how many of them end with exclusion,” he says. “Shylock is left out at the end of The Merchant of Venice, Malvolio is left out at the end of Twelfth Night. Characters create community by whom they leave out, ostracize, stigmatize. The comedies become a historical road map of whom we are now leaving out and stigmatizing. They become a way of revealing things that are not so great about this great country.”

Mary Cregan GSAS '95

The Brooklyn native attended grad school at the University of Chicago, then joined the Columbia faculty in 1985. “I learn a lot from teaching,” Shapiro says. “It’s important to hear what young people have to say because there’s a break between one generation and the next that’s quite sharp right now. The classroom is one of the few places where you can bridge that divide, or at least try to hear and see a little bit more clearly how generational interests diverge.

“I need to mix it up with students, I need to push and be pushed back,” he continues. “It’s a very New York style.”

In the late aughts, Shapiro realized that after decades of Shakespeare scholarship he knew very little about American history. In an effort to connect the dots, he started teaching undergraduate and graduate seminars on the American response to Shakespeare, and wrote a 2012 anthology for the Library of America.

Shakespeare in a Divided America’s narrative culminated for Shapiro after the 2016 election and a controversial theater production the following summer. The Public Theater staged Julius Caesar at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park and director Oskar Eustis chose to portray Caesar as a modern-day Trump lookalike. Shapiro, the Shakespeare scholar-in-residence at The Public, was at nearly every performance and witnessed protesters attempting to attack the actors and disrupt the show. His book opens and closes with discussions of what the production meant for free speech and artistic freedom. “Everything that I’ve been trained to do and have lived through has led to this,” he says.

“The danger of being a professor is getting stuck in time; you always have to be open to what’s happening at a particular moment,” he says. “[Writing this book] forced me to confront things that are harder to define, like racism and discrimination — who admits to being racist, or to being against someone with a different sexual orientation or gender? This book allowed me to get behind that wall. You’d be amazed what people will admit to through Shakespeare that they will not admit otherwise.”

Becoming a professor was an easy career choice for Shapiro. Both his parents were public school teachers, brother Michael teaches in the Journalism School, sister Jill BC’80, GSAS’95 is a senior lecturer in ecology, evolution and environmental biology at the College and wife Mary Cregan GSAS’95 teaches in the English department at Barnard. Son Luke was awarded a 2019 Euretta J. Kellett Fellowship and is studying at Oxford; Shapiro hopes he will follow in the family’s faculty footsteps.

Shapiro says that for him, a nice thing about Shakespeare is that it straddles work and play. In addition to teaching, he’s currently contributing to several theatrical productions and will soon embark on a book tour. “It’s all-consuming,” he says. “There are really not enough hours in the Shakespeare day!”

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu