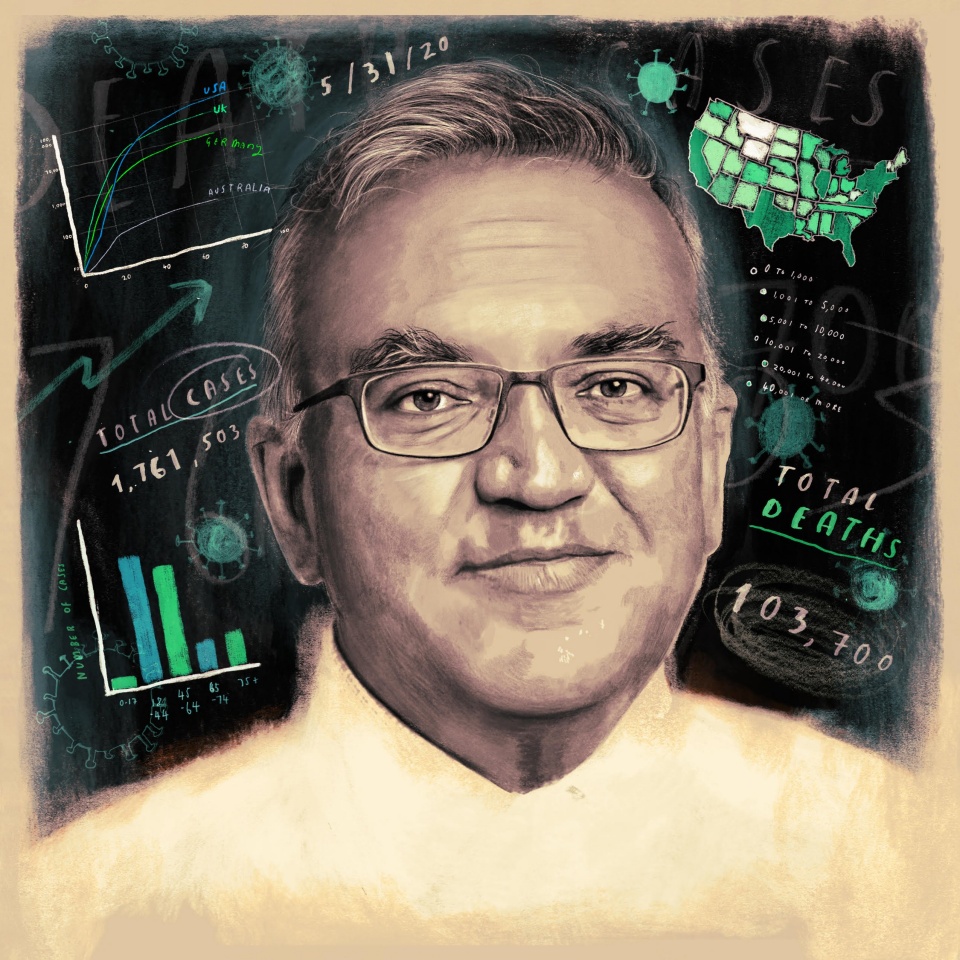

A leading authority on public health policy and programs delivers some straight talk about the virus that has killed more than 110,000 Americans and has the world reeling.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

A leading authority on public health policy and programs delivers some straight talk about the virus that has killed more than 110,000 Americans and has the world reeling.

A

ILLUSTRATION BY PETER STRAIN

Originally from the state of Bihar in northeast India, Jha’s family emigrated to Canada in 1979 and settled four years later in Morris County, N.J. As a pre-med student at the College — an experience he calls “transformational” — he concentrated in economics, played on the Ultimate Frisbee team, led the campus chapter of Amnesty International and was president of Earl Hall’s Student Governing Board. He earned an M.D. from Harvard Medical School and an M.P.H. from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, where he is the K.T. Li Professor of Global Health. An authority on healthcare systems, he has published hundreds of academic papers, advised government policymakers and elected officials, and taken on leading roles in the response to the Ebola epidemic and COVID-19. In September, Jha will assume the deanship of Brown University’s School of Public Health. He lives in Newton, Mass., with his wife, Debra Stump, an environmental lawyer, and their three children.

CCT spoke to Jha by telephone in late May to shed further light on the crisis. Following are edited excerpts of the conversation:

Columbia College Today: It has been more than a century since the last devastating global pandemic. What is different about this coronavirus that makes it so lethal?

Dr. Ashish K. Jha ’92: One reason is that there is no natural immunity to this virus in the human species. This is not like influenza, where the strain of the virus is a little different every year, but we have vaccines that are at least somewhat effective — plus all of us have a certain amount of natural immunity because we’ve all encountered influenza. This is a novel virus, for which there’s no immunity in the entire population.

A second part of it is, it’s very contagious. As opposed to “SARS classic,” as we say — the first coronavirus of 2003, which caused the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong, China and Canada — this one spreads much more easily. It’s not quite as lethal as the SARS virus, but it is much more infectious. Even more so than its cousin, the MERS coronavirus, which caused Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. MERS is very deadly, but very hard to spread.

So this virus has hit that unfortunate sweet spot: It’s probably about 10 times more deadly than a typical influenza virus — close to as deadly as the influenza virus of 1918 — and it spreads very quickly across the population.

CCT: Are we going to get through this? What are the most likely scenarios?

Jha: We will get through it. What I’ve been saying is that we’re in the third inning of a nine-inning baseball game. It largely comes to an end when we have a vaccine that’s safe, effective and widely available, and a vast majority of the population has been immunized. I expect and hope that this can happen for a large part of the United States sometime around June or July of 2021. Globally it may take longer. Until that time, this is going to be very hard — I’m deeply worried about what will happen in the fall and winter. Just as we saw with the Spanish Flu of 1918, I expect that there will be a large second wave that will coincide with influenza season, usually somewhere between November and February.

Most public health experts are more pessimistic. They would say that summer is going to be hard, with 1,000, 1,200, 1,500 people dying every day, and then we get crushed in the fall with large outbreaks into October, November, December. In this scenario, our economy largely shuts down for three months, schools and universities are closed, and the vaccine is nowhere close. A lot of experts think that we may not even have a vaccine in 2021, or that it’s not until 2022 that we really start putting this behind us. I say this with some trepidation, but I think they’re being too pessimistic. Let me give you two takes on why I think my optimism is warranted.

First, there are 100 vaccine efforts that I am aware of, eight that are already in clinical trial [as of late May]. It’s entirely possible we’ll have six vaccines that work by the end of the year, or just one or two. As long as there’s one that is effective and safe, that’s good enough. So we’re taking a lot of shots on goal, as it were. The chances that one of them will go in are extremely high.

Second, with so much political and economic focus on this, the moment that it appears one vaccine is likely to work, we’re going to start producing tons of doses. By the end of summer, I think we should probably start making hundreds of millions of doses of five vaccines. It may turn out that four of them don’t work, but even if we waste billions of dollars, it would be money well spent, given the cost of delay in terms of economic shutdown. The chance that none of these vaccines will work is exceedingly low.

Jha at Brigham and Women's Hospital

Courtesy Harvard Global Health Institute

Obviously there’s a lot we don’t know. But the basics of public health 101, of testing, of tracing, of isolation, of social distancing — this is literally how humanity has gotten through pandemics for centuries. Well, the testing stuff is a bit more recent. What has been amazing to me is that we have failed on those basics. So we’re hoping for a vaccine to bail us out. And it will on some level, but not without enormous cost. I think much of that cost could have been avoided.

CCT: What most urgently needs to be done by the U.S. government in response to the pandemic?

Jha: There is no federal response. The kinds of things we’ve been doing are all happening at the state level, with very little guidance — and often very contradictory guidance — coming from the federal level. What you ideally want is a kind of national blueprint, and then individual states being able to tailor that national doctrine or national guidelines with the help of local CDC officials. The approach to opening up restaurants in Montana probably ought to look different than it does in Manhattan.

I’ve always believed that public health in America was a state/federal partnership. The deal that we had forever was that the states would lead on public health, but that the federal government would provide technical guidance, intellectual resources, financial resources and coordination across states, especially when you got into national disease outbreaks. And mostly, the federal government is not living up to its end of that bargain.

CCT: Why hasn’t that happened, do you think?

Jha: The short answer is that I don’t know. Part of the White House strategy is, “Well, let’s blame the states, let’s say that the reason the U.S. response is so bad is because we have 50 failing governors, none of whom could figure out what to do.” Of course, that’s absurd. Most of the governors have actually been terrific. The federal government just doesn’t seem interested or willing to do the hard work.

CCT: You’ve been outspoken in expressing your dismay at the performance of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

Jha: Until this pandemic, the CDC was the most influential, effective, important public health agency in the world. What it did was what the rest of the world’s public health agencies followed and emulated. The CDC had, and still has, some of the best public health scientists in the world.

What has become very clear is that the CDC was told it can’t release any messaging or information to the public without running it by the White House. That has substantially hampered it. Clearly, all of its scientific guidance is seen through a political lens. That has meant that detailed information going to governors, mayors, private businesses and school leaders about how to open up our country — all of that stuff has gotten blocked. Eventually it made its way out because of leaks. But that’s not how we’re supposed to be doing these things.

There had also been some missteps, like botching the initial test [for coronavirus]. But the CDC really has been hampered in its ability to fix any of those things. It’s a really unfortunate situation when the world’s leading public health agency has been sidelined.

“I think the scientific enterprise is going to bail us out of all of this.”

CCT: I’m sure you and others are considering what we need to do to be ready for a future pandemic, in terms of research, industrial capability, stockpiling, disease surveillance, information technology and international cooperation. What else needs to be considered?

Jha: I think we also need to have a conversation about global governance and the role of the World Health Organization. Member states have put very specific restrictions on WHO over the years and have limited its ability to do certain things, and then WHO gets beaten up for having failed to do them. So we need to consider, what is the role of WHO? Do we want a much more independent WHO? How would it function? Because otherwise we’re left to the whims of individual member countries, all acting in an uncoordinated way, which has been a hallmark of this pandemic’s response.

CCT: The pandemic has also performed a kind of X-ray or stress test on society, highlighting our shortcomings and inequalities in terms of race, income, healthcare systems, living conditions, food security and more. But a crisis can also create opportunities for positive change. In the field of public health, what changes would you most like to see come out of this?

Jha: One thing that I hope and believe will happen is the American public will understand much more clearly the value of investing in a strong public health infrastructure. We have an $800 billion military that can’t do much to protect hundreds of thousands of Americans from getting sick or dying. I think we should have a strong military, but that’s not enough, because weaknesses in our public health infrastructure can sideline us every bit as much, if not more, than a hostile nation state or a terrorist organization. So that means substantial investments in public health across the country, from surveillance to platforms for drugs and vaccines.

I also think this experience will push medical education to incorporate public health principles much more. When we fail in public health, it’s physicians and nurses who have to essentially deal with the brunt of it. I mean, obviously it’s the American people who have to deal with the brunt of it, but the failure of political leadership has meant that we have hundreds of thousands of physicians and nurses on the front lines risking their lives to try to make up for those failures.

CCT: Would you say we need to acknowledge our reliance on the workers who perform critical and dangerous work on the front lines, including EMTs, and give them higher pay, loan forgiveness, perhaps other benefits?

Jha: Absolutely. Because in this pandemic, they have been the saviors. Even in the middle of the biggest outbreaks, you knew if you called 911, somebody would show up to your door and take care of you. And those people got sick and died at alarming rates. We need to reevaluate how we demonstrate that we value what they do for society, beyond just clapping for them. Our policymakers basically said, “We’re not going to give you the protective equipment you need, but please, take care of all these sick patients.” We should be asking not just what are our ethical duties to take care of the sick, but also what is society’s duty to make sure nurses, physicians and other workers are protected.

CCT: How has the pandemic touched you personally?

Jha: In many ways. I have close family friends who have gotten sick and died. The most tragic for me is a very close cousin, somebody I grew up with in India — he died two days ago. He was having chest pain and could not get anybody to see him, because all the doctors’ offices were closed. He didn’t die from COVID, but he died as a result of the way that COVID has made our healthcare systems so deeply dysfunctional.

CCT: Did your experience at the College leave an imprint that influences your work and outlook today?

Jha: Those four years were certainly the most important years of my life intellectually and personally. Part of it was having incredible mentors, the most important of whom was [former University Chaplain] Rabbi Michael Paley. I went to a high school that, to be perfectly frank, was racist, and I was one of the very few non-white people in that school. I came out very confused because I felt like I should be ashamed of being an Indian yet it was such an important part of who I was. Among the many great things I learned at Columbia was that I could be Indian and I could be American. There was no contradiction. Rabbi Paley described his own experience growing up as a Jewish kid in Brooklyn and having identity issues, and realizing that one of the things that America afforded you was the ability to hold what some people see as a contradiction — the idea that I could be culturally Indian, feel authentically Indian, and yet be also very American at the same time. One of the most important books I read at Rabbi Paley’s suggestion was The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

I also remember taking Literature Humanities with Wallace Gray, and recognizing that I was not the first person in human experience to discover these issues of self-identity and culture. We were reading about people in Greek and Roman literature who had struggled with the same things in slightly different ways and with slightly different manifestations. The really powerful part of the Core Curriculum was the universality of the underlying principles. That has certainly shaped how I’ve thought about almost everything in the work that I’ve done over the years. I don’t know if I’ve ever gone back and connected it in quite that way until right now.

I walked out of the College much more confident in my personal identity. That has allowed me to take many more risks, try new things, question what borders I have to live within. There have been moments in my career when it’s been, “Are you a doctor or are you a policy person?” And I’m like, “How about both?” That sort of ability to take risks and think intellectually outside of silos, I feel like I really learned that at Columbia. It was transformational. It changed everything that I did afterward, and therefore, obviously, I have very fond feelings toward the institution. I’m confident that it has done that for thousands of people over the years.

Former CCT editor Jamie Katz ’72, BUS’80 has held senior editorial positions at People, Vibe and Latina magazines and contributes to Smithsonian Magazine and other publications. His latest piece for CCT, “The Denial of Science: We’re in Hot Water,” appeared online in January.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu