By Jill C. Shomer

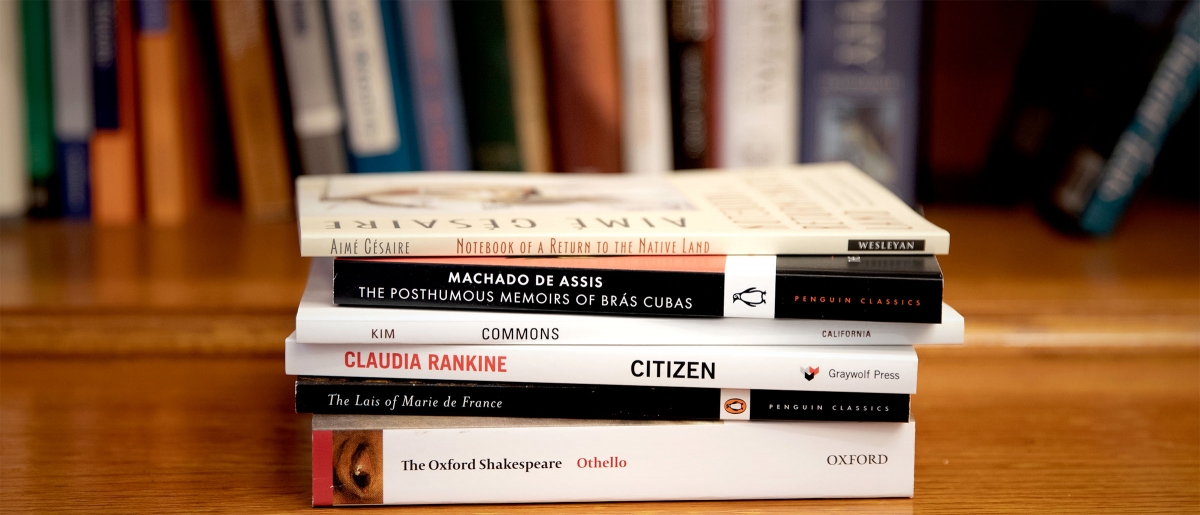

Enheduanna. Apuleius. Aimé Césaire. Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis.

These are just a few of the authors being read this year in Lit Hum. You might not recognize the names — but that’s actually a main point of the most recent syllabus reform.

“Today’s Lit Hum students are eager to trouble assumptions about what makes up literary canon,” says Joseph Howley, associate professor of classics and the future chair of Lit Hum. “They understand that canon formation is historically linked with power, and that canons can be used to exclude people. This means they are curious about what gets left out.”

By offering stories from people and parts of the world previously unheard from, the 10 new works (and two that were successfully incorporated during the last two years) enrich the diversity and cultural representation of the Lit Hum syllabus. Collectively, they expand students’ understanding of “Western literature,” and inspire new discourse alongside texts that have been on the syllabus for years.

Texts added to the Fall term included The Exultation of Inana, by the Sumerian poet and high priestess Enheduanna; the Babylonian creation myth Enuma Elish; Life of Aesop; and the earliest surviving novel in Latin, The Golden Ass by Apuleius. The Spring term includes, for the first time, novels from South America (The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubás by Joaquim Maria Machado de Assis) and the Caribbean (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land by Aimé Césaire), as well as two works of contemporary 21st-century poetry, Myung Mi Kim’s 2002 Commons and Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric from 2014.

Parallels and New Perspectives

Suggestions and guidance for the syllabus reform came from both undergraduates and instructors. To discuss how these new texts enrich the student experience of the course, we spoke with Howley; Joanna Stalnaker, professor of French, and former Lit Hum chair; Nicholas Dames, the Theodore Kahan Professor of the Humanities; and T. Austin Graham, associate professor of English and comparative literature.

The professors were unilaterally enthusiastic about introducing the new texts, and are excited about the parallels found alongside Greek and Roman texts and the Bible. Speaking about his experience teaching the new Sumerian and Babylonian readings, Graham says: “Several of the Lit Hum texts take up similar issues even when they’re historically or geographically distant from one another. Both Enuma Elish and ‘Genesis’ are creation stories, and invite us to ponder fundamental questions: What existed before the world did? Were humans created with a purpose in mind? I also enjoyed thinking about The Exaltation of Inanna and the Book of Job alongside one another: They’re both stories about individuals who suffer, and who cry out to the divine, and who feel that their particular experiences of pain have cosmic implications. I love the opportunities for dialogue and comparative reading that these new texts give us — they invite us to think about their continuities with and departures from the other books.”

Importantly, the enhanced syllabus also speaks to one of the Core Curriculum’s original missions: to prepare undergraduates to address “the insistent problems of the present.” Students have asked for acknowledgement of the social realities and politics found in Lit Hum texts; for example, finding ways to discuss the presence of sexual or gendered violence, or of slavery. “Slavery is a defining aspect of life in the Greek and Roman world; it’s alluded to regularly, but none of the texts are about it, or equip students to talk about it directly,” Howley says.

“The choice in 2019 to add Father Comes Home from the Wars — a set of interlinked stories [by playwright Suzan-Lori Parks] about the experience of enslaved people in the time of the American Civil War, that echoes and works with Homer’s Odyssey and also Orestia — started helping us build that bridge. And I think we had an opportunity to expand it further.”

The newly added Life of Aesop is one of the few texts from the ancient Greek and Roman world about the experience of an enslaved person and the experience of enslavement. “It really complicates and enriches the students’ view of the ancient world, and it speaks to glimpses we get of enslavement in other texts,” Howley says. “This really helps us be able to say that when the students are encountering the ancient Greeks and Romans in Lit Hum, they’re really encountering all of them, or at least more of them.”

Similarly, Dames offers the reason he championed the addition of Césaire’s Notebook of a Return to a Native Land for the Spring term: “There was nothing on the Spring syllabus that directly confronted colonialism, and it felt like a lacuna that needed to be filled,” Dames says. “Césaire fits that way, but I was also intent on not adding another American work or another work in English — this was the first work on the syllabus from the Caribbean, written in French by a Martinican poet. It introduces a perspective on colonialism and the African diaspora from a part of the world students may be less familiar with. But it’s also literarily interesting and very complex; a hybrid between poetry and prose that students won’t have a handle on yet.”

Dames also observed how Machado’s novel The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubás, which is now read between Austen and Dosteyevsky, offers thematic parallels about narration. “With Austen we see for the first time in the course: ‘Here’s a story; I’m going to narrate it to you,’ which raises the question of ‘Whose story is this?’ And in both Machado and then Dostoyevsky, that relationship is even stranger, in that the narrator doesn’t live in the world that they narrate. “Another way to think about it is, these are written by novelists who lack socioeconomic privilege. Jane Austen is writing as a woman in 1813, and Machado is a grandson of freed slaves. They exist in this interesting inside/outside position culturally, and I think that’s a provocative way of thinking of those two novels together.”

The Lit Hum syllabus receives a triannual review, which Howley believes is a good thing. “[Syllabi] should be living documents,” he says. “The other thing to remember is the canon has never been constant. This stuff is always in flux, and we have to find a balance between the names that people know and the names that people don’t. We can’t just keep saying ‘We’re going to teach this because we’ve always taught it.’ We’ve got to do better, and the students expect us to.”