M

arking the end of the four-year transition from the all-male school it had been since 1754, Columbia College graduated its first fully coeducational class 25 years ago this spring. Nearly half the students who donned sunglasses and mortarboards on that bright May afternoon were women, and while the fanfare that had accompanied their freshman year focused largely on their presence, the celebration by the end of senior year had shifted to their accomplishments: Most of the Class Day awards went to women, and the valedictorian, salutatorian and class president were all women. Collectively, their leadership and academic success made a powerful statement about how women had enhanced the life of the College.

And their impact was only just beginning.

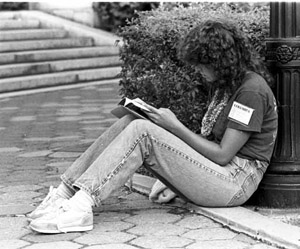

On break during orientation, August 1983. PHOTO: JOE PINEIRO, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

“We broke through that glass ceiling at Columbia, and women continue to break through glass ceilings in many areas, nationwide,” says Julie Menin ’89, chairperson of NYC’s Community Board 1 and a candidate for Manhattan Borough President. “I remember all those times sitting in Lit Hum and other Core classes, and especially my political science classes. Those courses and my experience at Columbia were vital in laying the foundation of what I’m doing today, and my interest in politics and government. It’s why I became a regulatory attorney and why I’m running for office.”

On break during orientation, August 1983. PHOTO: JOE PINEIRO, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

“We broke through that glass ceiling at Columbia, and women continue to break through glass ceilings in many areas, nationwide,” says Julie Menin ’89, chairperson of NYC’s Community Board 1 and a candidate for Manhattan Borough President. “I remember all those times sitting in Lit Hum and other Core classes, and especially my political science classes. Those courses and my experience at Columbia were vital in laying the foundation of what I’m doing today, and my interest in politics and government. It’s why I became a regulatory attorney and why I’m running for office.”

The first coed class, 1987, made a grand entrance, starting with admissions and following through to graduation. “The women who arrived were extremely motivated to be intellectually, athletically and affectively engaged in the life of the college,” says Hannah Jones ’87, president of the senior class and now a seventh-grade humanities teacher in Cambridge, Mass. “We had the backing of administrators and peers. What a crop of progressive, and basically nice, men with whom we went to college. We also had our path-breaking sisters at Barnard, who were already taking Columbia College classes and living in Columbia College dorms.”

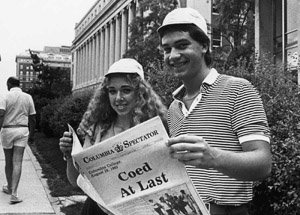

Donning their beanies, two first-years mark the start of a new era on August 29, 1983. PHOTO: JOE PINEIRO, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Donning their beanies, two first-years mark the start of a new era on August 29, 1983. PHOTO: JOE PINEIRO, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Columbia received 55 percent more applications for the Class of 1987 than for the all-male Class of 1986, and selectivity improved from 40 percent accepted the previous year to 31 percent accepted. (The trend has continued, with 6 percent of applicants accepted to the Class of 2015.) In 1983, the final tally for the incoming class included 357 women, 45 percent of the total of 800. The students also were more geographically and ethnically diverse than in previous years and collectively had a much-improved student profile in terms of test scores and high school class rankings. “The College got better, more diverse and rejuvenated in the teaching as well,” Robert Pollack ’61, professor of biological sciences and dean of the College from 1982–89, told CCT in 2009. “It became a safer, happier, more interesting place.”

“Many of the women Columbia attracted in its first coed class were truly intrepid,” says Linda Mischel Eisner ’87, the class valedictorian. “The neighborhood around Columbia today bears only a hint of resemblance to the neighborhood in 1983. New York City’s then-gritty Upper West Side near Morningside Heights was its own frontier as much as coeducation was.”

The first women who attended Columbia were independent and assertive. They immediately stepped into leadership roles on campus, holding about 75 percent of those positions at the end of their four years. “There was a ‘beat the boys’ mentality among the women, that perhaps our male counterparts were unaware of — perhaps we had set up a competition that they did not perceive or felt was irrelevant,” Jones says. “I felt proud for what women in our class had achieved by graduation in all realms of Columbia College.” Among the prominent organizations with women at the helm were the Columbia Volunteer Service Center (president, Vania Leveille ’87) and the United Minorities Board (chair, Annie Fils-Aime ’87), precursors to Community Impact and the Intercultural Resource Center, respectively.

Former University President Michael Sovern ’53, ’55L has joked that on Class Day 1987, “The only men on the program were from the administration!” In addition to the achievements of the valedictorian and salutatorian, women won a great number of the awards. “That added to the excitement and to the feeling that women in the class had excelled in uncommon ways,” says Mischel Eisner.

Women have shone both on campus and as alumnae ever since. Mischel Eisner, for example, a computer science major, worked after graduation as a quantitative analyst developing financial software, then earned a J.D. from Yale, was a tax attorney and now is in the public sector as a federal judicial law clerk. “With my Columbia College education to ground me, I am always ready to take on the next challenge,” she says.

“Is there any aspect of my life that would be the same if I’d gone to another school? No,” says Kendra Crook ’95, an M.B.A. prep coach for the nonprofit Management Leadership for Tomorrow. “My intense love for New York City, how I approach things, why I’m good at my job, my appreciation for diversity ... How did I go from being a white girl in Maine, with not a single black face in my high school, to working now to help minorities get into business school? My first-year roommate was black, my suitemate was Asian, a lot of my basketball teammates and classmates were African-American and Hispanic. When you live like that on campus, you start to think, ‘This is the way life should be.’”

Y

ears ago, before coeducation at Columbia, that sentiment was reversed: It was the College campus that needed to reflect the reality of the outside world. As a College student in 1980 noted in a campus survey: “Life is coed, school should be also.” By the early ’80s, secular, all-male colleges were nearly extinct; the other Ivies and even the five U.S. military academies were enrolling women. How could Columbia, as part of a large university in the middle of a cosmopolitan city, make the transition so late?

In a word, Barnard. The undergraduate school for women had been established in 1889, in part through the rallying efforts of Annie Nathan Meyer, a student in Columbia’s Collegiate Course for Women. (CCW allowed women to enroll in a home-study program and sit for exams alongside male students for the same credit, but Meyer and others wanted a more substantive education for their female peers.)

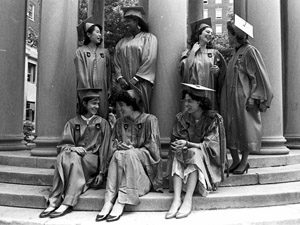

Members of the Class of 1987 gathered at the Van Amringe Memorial: (standing, left to right) Kokoro Kawashima, Vania Leveille, Marya Pollack and Shelley Coleman; (seated, left to right) Ilaria Rebay, the salutatorian, Linda Mischel, the valedictorian, and Hannah Jones, class president. PHOTO: JOE PINEIRO, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Members of the Class of 1987 gathered at the Van Amringe Memorial: (standing, left to right) Kokoro Kawashima, Vania Leveille, Marya Pollack and Shelley Coleman; (seated, left to right) Ilaria Rebay, the salutatorian, Linda Mischel, the valedictorian, and Hannah Jones, class president. PHOTO: JOE PINEIRO, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Starting in 1973, the College and Barnard allowed cross-registration of most courses, the Core excepted, and by the mid-’70s a portion of undergraduate housing had become coed through a Barnard exchange program. But the coed experience remained quite limited for College first-years, who took Core classes not open to women and most of whom lived in all-male Carman Hall. A faculty resolution in 1975 and student surveys in the early ’80s offered some of the first concrete proof that the status quo had become unacceptable to most faculty and unappealing to most students. As Roger Lehecka ’67, ’74 GSAS, dean of students from 1979–98, previously told CCT: “A vanishingly small number of students came to Columbia College because it was an all-male college, and many came because they had been led to believe that Columbia and Barnard students’ lives were more together than they actually were.”

Carl Hovde ’50, dean of the College from 1968–72, and Peter Pouncey ’69 GSAS, dean from 1972–76, promoted the idea of coeducation, perhaps by merging or partnering with Barnard. But Barnard was uninterested in such a path, as it had a firmly established identity and functioning structure as a women’s college and already offered its students the benefits of being part of Columbia University. “In the end, what many of us failed to understand is that Barnard wanted to be what it was, a women’s college, and Columbia didn’t want to be what it was, a men’s college,” Lehecka said.

The turning point came in 1980, when Dean Arnold Collery, a strong supporter of coeducation, appointed a committee of faculty and active alumni to examine the coed question. Ronald Breslow, professor of chemistry and University Professor, chaired the committee. “Everyone had a feeling the only choice was to fuse with Barnard, and Barnard would be swallowed. It was sort of a stalemate,” Breslow told CCT in 2009. “From Barnard’s point of view, there was no advantage to going coed, but we [the College] couldn’t afford not to, from a competitive standpoint. Collery deserves a lot of credit for deciding something had to be done.”

Breslow and his committee replaced assumptions with research. They looked at about a dozen other places where a formerly all-male college in proximity to a women’s college had gone coed. In each case, the women’s college survived. A prime example was Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s, located as Columbia and Barnard are, across the street from each other.

The committee also analyzed where College applicants would come from, and reported that Columbia College would not compete with applicants to Barnard as much as with applicants to schools such as Penn and Princeton. The Breslow committee concluded that a coed Columbia and a healthy Barnard could coexist. The report was presented to Collery, who “was wildly enthusiastic about it,” Breslow said, and subsequently to Sovern. Sovern took the findings to the University Trustees, who in December 1981 approved making the College coeducational.

The arrival of the first female students in fall 1983 brought much excitement to campus andcoverage in the media, and in the following years, many women from the Class of ’87 and otherearly coed classes felt proud to be trailblazers. “It was a spectacular place, and I couldn’t havefelt more welcome,” says Lisa Carnoy ’89, co-head global capital markets, Bank of America Merrill Lynch,and a University trustee. “Every opportunity was available to me: every course, activity andleadership role. And the Dean of Students Office, under Roger Lehecka, made a huge difference.”

Others were less attuned to their pioneering status. Dr. Laura Brumberg ’87, who always had wanted to go to Columbia, recalls her high school guidance counselor telling her, “You’re in luck, they’re accepting women this year.” Brumberg hadn’t known the College had been all-male.

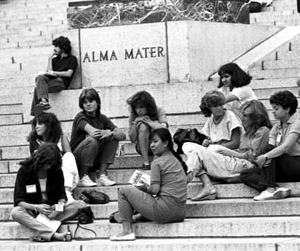

Women accounted for about 45 percent of the incoming freshmen in 1983. PHOTO: JOE PINEIRO, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Women accounted for about 45 percent of the incoming freshmen in 1983. PHOTO: JOE PINEIRO, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

In many ways, the first-years in 1983 arrived to an already changed campus. Carman Hall, where most of the incoming female students would be housed, had undergone a nearly $1 million rehabilitation during the summer: new paint, furniture and carpeting; repairs to radiators, bathroom appliances and locks; and a redesigned main entrance and lounge. (Pollack, then in his new position as dean, saw coeducation as an opportunity to improve life for all students, and he pushed for renovations to residence halls along with guaranteed housing for students for all four years.) A new Women’s Health Center was set to open in John Jay. The College’s Counseling Service was expanded, and educational programs addressing issues such as sexual harassment and staying safe were instituted.

On the athletics front, women began competing on varsity teams as part of the newly established Columbia-Barnard Athletic Consortium. Its creation was negotiated by Pollack as a novel solution to Title IX, the federal law that requires equal educational programs and activities at all schools that receive federal funding. The consortium included women from the College, Engineering and Barnard, and moved existing Barnard teams from Division III Seven Sisters to Division 1 Ivy League competition. There were women’s teams in fencing, tennis, basketball, track and field, cross country, swimming and diving, volleyball and archery.

Women’s presence in the classroom also focused attention on imbalances in the curriculum and the overwhelmingly male faculty. Both needed updating to reflect the reality, not only in the College but also in society, that women were taking their places as equals. Pollack and Michael Rosenthal, associate dean of the College from 1972–89 and the Roberta and William Campbell Professor in the Teaching of Literature Humanities, met with humanities and social sciences departments to discuss the implications of coeducation, sensitivity in the classroom, the need for eventual course changes and the hiring and tenure process. Though change in these areas was slower to take hold, a major was added in women’s and gender studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender was established in 1987 and Core content was tweaked: Jane Austen was added to the Literature Humanities syllabus in 1985, Sappho in 1986 (and removed in 1992) and Virginia Woolf in 1990.

The transition to coeducation went smoothly in part because the College is, by population, a small part of the larger university. Women undergraduates had been attending Barnard, Engineering and GS, and student activities and most courses had been mixed-gender for years. “When we were at the College, we weren’t thinking about how recently the college went coed, except for the number of women’s bathrooms in Hamilton, which everyone made a joke about,” says Claire Shanley ’92. “Our experience was blended; we had friends at Barnard and Engineering and Columbia College. It wasn’t always palpable that this had so recently been an all-male institution.”

Stand, Columbia women! The first fully coeducational class graduated on May 13, 1987. PHOTO: JOE PINEIRO, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Stand, Columbia women! The first fully coeducational class graduated on May 13, 1987. PHOTO: JOE PINEIRO, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

The College’s single-sex history became quite evident, however, after graduation, when the relatively few women entered a nearly all-male alumni pool. “I reached out to men, who gave me advice,” Carnoy says. “Jerry Sherwin [’55] was my first mock interviewer.”

As Jill Niemczyk Murphy ’87 found, some alumni didn’t even realize women were being admitted. After graduating she called a senior partner at a law firm to try to network. “He said, ‘Well, you couldn’t have gone to the College,’” Niemczyk Murphy recalls. “In the early years, you’d tell people you went to Columbia and they’d say you must have gone to Barnard. It took a while for people to internalize that.”

“The energy of the coed classes is very different,” says Kyra Tirana Barry ’87, president of the Columbia College Alumni Association (CCAA) and the first alumna to hold that position. “Since we graduated, there have been women who’ve been engaged and members of the Alumni Association Board of Directors and the Board of Visitors but it takes time and it takes numbers to change the culture and see a shift in the cultural tradition. As we hit this mark of being 25 years since graduation, the time is right and the energy is right for women to have a larger role.”

Recognizing that alumnae are a distinct group with different perspectives and preferences than their male counterparts, the Alumni Office in 1989 helped form Columbia College Women. CCW has grown from a handful of women who met in one another’s apartments to a more visible group that has an executive board, runs a sizeable mentoring program for students and funds a current-use scholarship each year.

“I didn’t make a lot of friends on campus. Once I left Columbia, I felt I should start meeting people, and wanted to build an alumni network,” says Siheun Song ’07, whose gateway to building that network was attending a CCW event at Dylan’s Candy Bar in Manhattan. She became involved with the group and now chairs the CCW executive board. “I’m very comfortable in a group of women, and having a group to address women’s issues is really important.”

Active participation in CCW, however, still is small compared to the number of alumnae. “Barnard has such great programs. I’d love to sit with them and learn from them,” Song says. “Barnard is more established, has a greater number of alumnae and is more experienced at communicating.” Aside from several joint reunion events, alumnae activities of the two schools remain largely separated.

In April 2010, another women’s group was formed, the Dean’s Alumnae Leadership Task Force, with a mission to engage more women in the life of the College. The 23 members have participated in outreach and fact-finding efforts including an alumni survey of members of the Classes of 1987–2010. “I think we’d all felt neglected in a way. There weren’t any women who’d been looking out for us,” says Sherri Pancer Wolf ’90, a member of the task force’s regional outreach subcommittee. Wolf hosted a luncheon for Boston-area alumnae, which was attended by the dean. “It was refreshing to find out there were so many successful, interesting women and that they wanted to be involved and engaged,” Wolf says.

Barry, a member of the task force in addition to being CCAA president, says, “We want alumnae to be connected because we want them to have a voice at the table and a leadership role in terms of determining how the College moves forward. Women in leadership positions in their careers and in the alumni network is aspirational for the women coming behind us.”

Wolf sent her daughters to all-girls high schools. “I’d only want to see them go to a coed college if it has a network in place to support them and guide their success,” she says. “I think Columbia has finally reached that point and it will only get better from here.”