Columbia College is a different and more fully realized institution today than it was before the arrival of that first class of women. And I think that much the same can be said for the university at large.

— Lee C. Bollinger, President of Columbia University

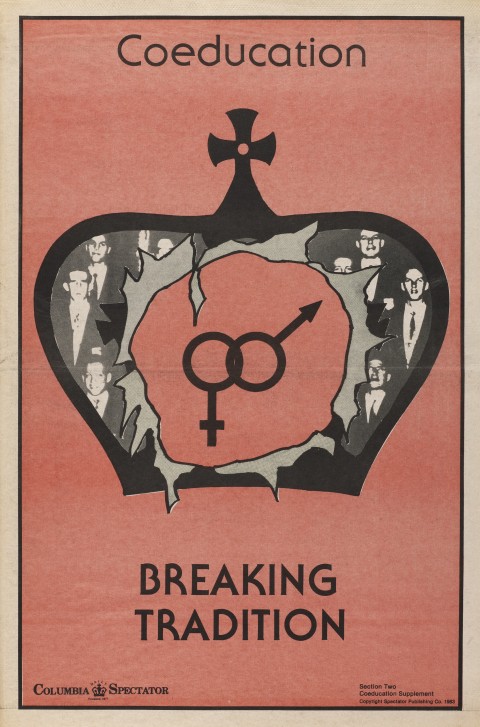

Though hard to imagine today, coeducation at top U.S. colleges and universities was not widespread until the late 1960s and the 1970s. Prior to this time, many institutions allowed for the education of women yet treated them as separate cohorts with unique “feminine curriculums” that focused on preparing them for domestic duties. Universities regularly expressed concerns that their schools might be viewed as “over-feminized” if too many women attended or performed too well academically.

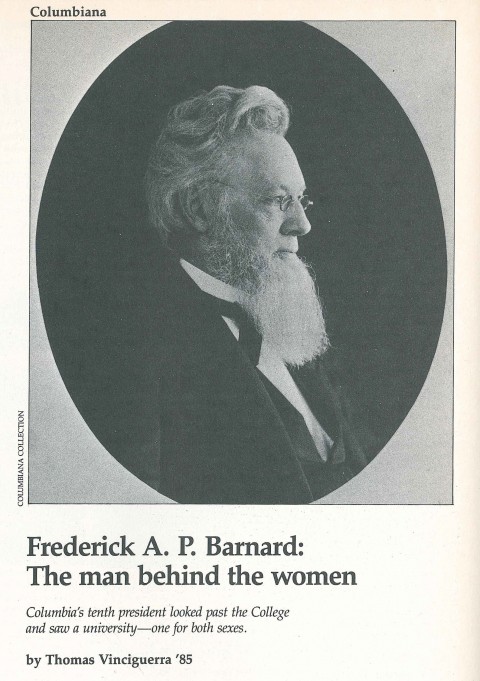

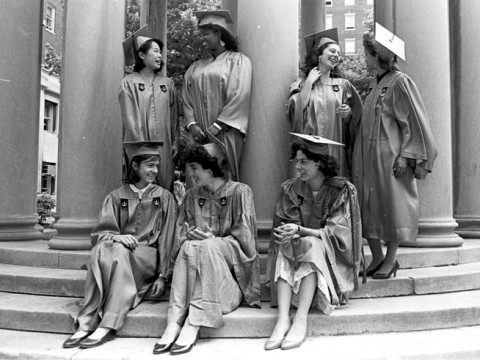

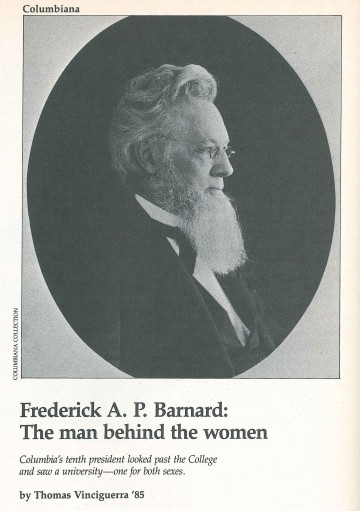

Columbiana Collection // Columbia College Today

On Columbia’s campus, as early as 1879, then-President F.A.P. Barnard first proposed the idea of College becoming coeducational in his annual report to his trustees. While the trustees decided against it, they agreed to the creation of a “Collegiate Course for Women” in 1883, permitting women to take exams but not take classes with men. One woman who was initially enrolled in the Collegiate Course for Women, Annie Nathan Meyer, rallied support for a women's college at Columbia and became instrumental in working with University trustees to establish Barnard College, which opened in 1889.

The social and political atmosphere of the next century, however, shifted the country’s social mindset significantly. Women were able to vote by 1920 and began joining the workforce throughout WWII. By the 1960s and 70s, women became more active in protest during the Civil Rights and Antiwar Movements, working alongside men to direct change and challenge the old order nationwide. This helped open the door for a frank discussion about issues such as equality for women, equal pay, women’s access to credit and other gender discrimination in society and the workplace.

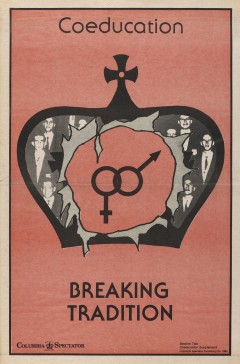

Based on this newly shaped ideology, not only did women take greater interest in pursuing education that allowed them equal opportunities outside of the home, but also male students expressed awareness that women in the classroom would lend greater diversity to academic discussions and would greatly enhance their social experience. A student poll in 1976 reported that 70 percent of Columbia College students were in favor of coeducation. By 1980, that percentage grew to 90 percent.

Life is coed, school should be also.

Columbia Magazine

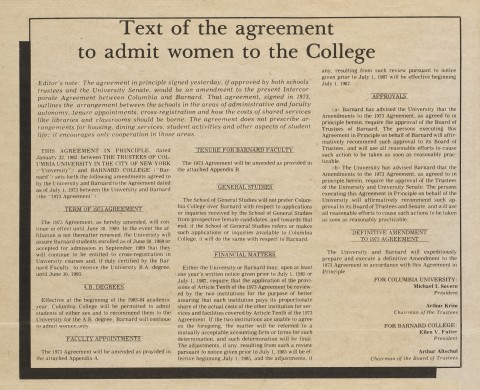

At Columbia, the long-asked question about coeducation at the College was inextricably tied to the existence and well being of Barnard College, which did not want to merge with Columbia College. The concern about Barnard’s future should women be admitted to the College was one of the reasons that coeducation was introduced later than at all other Ivy League institutions. In an effort “to increase integration without assimilation,” the Columbia-Barnard agreement of 1973 allowed for most classes to be open across the two schools. However, the College’s Board of Visitors insisted that then-Dean Arnold Collery find other ways to expand coeducation in the college. (Timeline via Columbia Daily Spectactor)

In the end, what many of us failed to understand is that Barnard wanted to be what it was, a women’s college, and Columbia didn’t want to be what it was, a men’s college.

—Roger Lehecka CC’67, GSAS’74, dean of students 1979–98

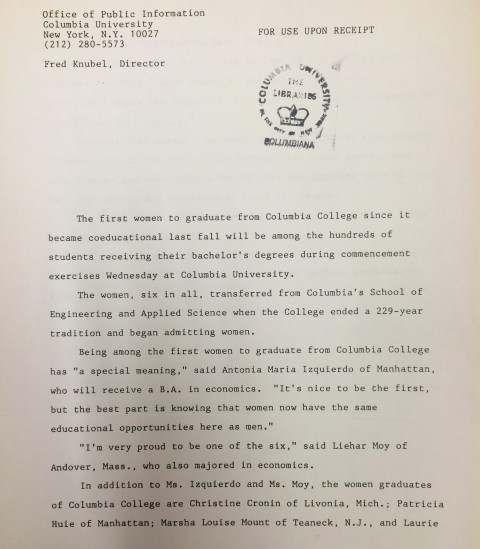

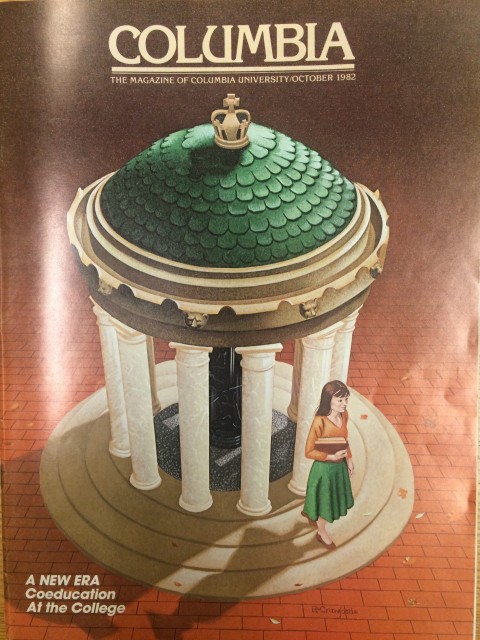

In 1980, a near-unanimous vote among Columbia College faculty prompted Collery to appoint a committee, headed by University Professor Ronald Breslow, to examine the effects of an all-male college going coeducational in close proximity to a women’s college. The Breslow Report demonstrated that in all cases, notably Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s, coeducation did not negatively affect the women’s college. Fears about Barnard’s future were allayed in winter 1982 when University Trustees signed the agreement to admit female students. (Read the 1982 The New York Times News Analysis)

The consensus was that the absence of women had diminished the quality of life at Columbia, and was hurting the school competitively. I remember as a student hating the absence of women.

—President Emeritus Michael Sovern CC’53, LAW’55

The College got better, more diverse and rejuvenated in the teaching as well.

—Robert Pollack CC’61, professor of biological sciences and dean of the College from 1982–89

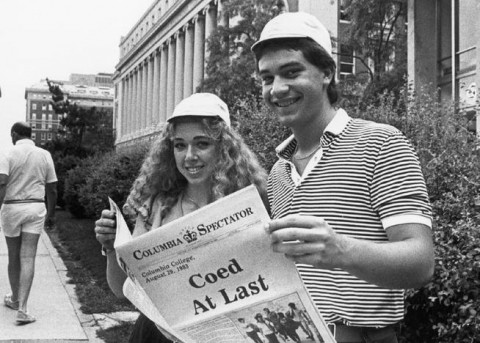

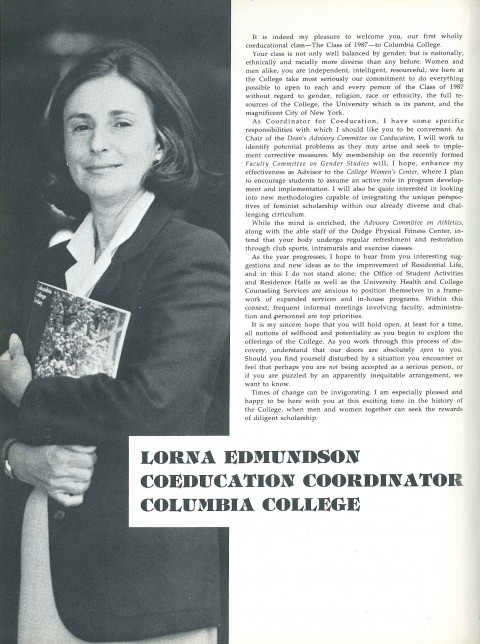

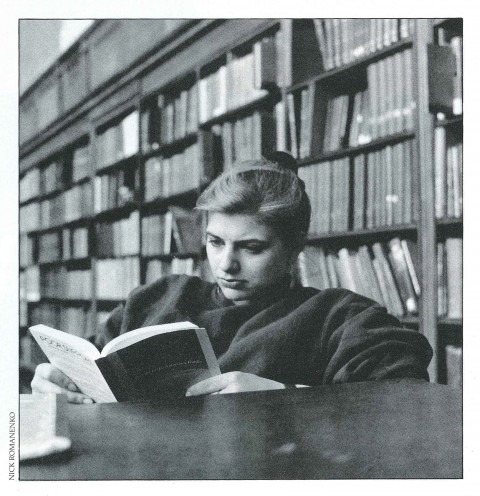

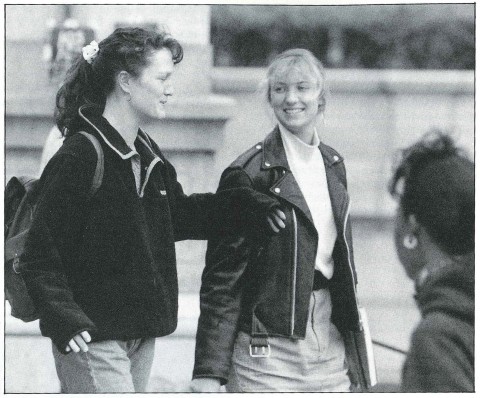

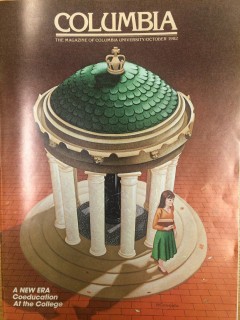

Changes were immediate when the incoming class arrived on campus in 1983. Not only had the academic curriculum been reexamined but the whole culture shifted. “The women that were here took leadership positions from Day One,” says University Trustee Lisa Carnoy CC’89. (Watch video)

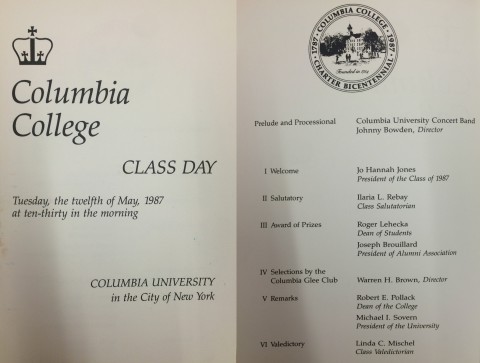

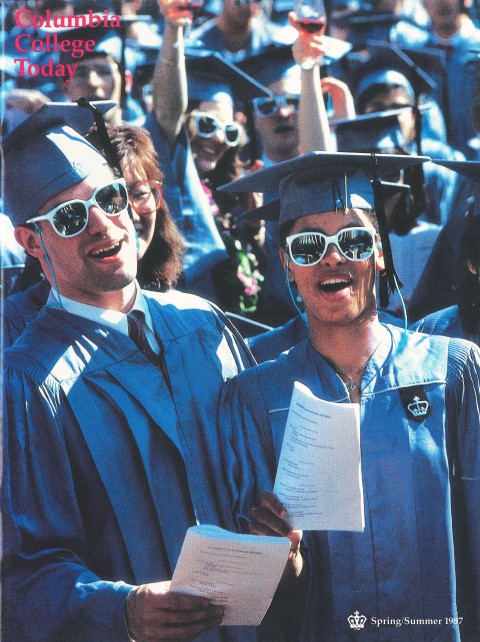

The College ended a more than 200-year-old tradition when the first fully coeducational class graduated on Class Day on May 12, 1987. Most awards that day went to women — including a female valedictorian, salutatorian and class president — making a powerful statement on leadership and success for women at the College.

We broke through that glass ceiling at Columbia, and women continue to break through glass ceilings in many areas, nationwide.

To this day, Columbia College alumnae and students continue to shape the future of Columbia College and the University at large.

See also:

- “Coeducation at Columbia” by Julie Golia GSAS’10 for Columbia University Archives

- “Class of 1987 Heralds New Era at Columbia” By Shira Boss CC’93, JRN’97, SIPA’98 Columbia College Today, Spring 2012

- “25 Years of Coeducation” By Shira Boss CC’93, JRN’97J, SIPA’98 for Columbia College Today, July/August 2009

Sources: Columbia College Today, Columbia Daily Spectator, Columbia magazine, “Keep the Damned Women Out”: The Struggle for Coeducation by Nancy Weiss Malkiel