The dawn of WKCR’s Jazz Age, described by the mavericks who made it happen.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

The dawn of WKCR’s Jazz Age, described by the mavericks who made it happen.

In the decades since, WKCR’s reputation has grown with fans and musicians alike; the latter especially appreciate the education it offers. “What made KCR different was the substance of its programming,” says renowned trumpeter and jazz educator Wynton Marsalis, adding that the musicians tuned in to learn. “You could always hear the music,” Marsalis says.

Phil Schaap ’73 in the WKCR studio in 1991.

JOHN ABBOTT

Sharif Abdus-Salaam ’74 hosting his show in 1972.

COURTESY SHARIF ABDUS-SALAAM ’74

Indeed, the famously encyclopedic Schaap, along with the ebullient Sharif Abdus-Salaam ’74 (né Ed Michael), have volunteered at the station near continuously to this day. They and other contributors from that seminal early ’70s period recently recalled what it was like working at the station during that ambitious, transformational time. This is their story, in their own words.

TOM NESI ’70, PROGRAM DIRECTOR, HOST “JAZZ ECHOES”: I didn’t realize before I came to Columbia that there was a professional FM radio station that I could simply join. It was just three blocks from my dorm. I started off as the correspondent for the U.N.

JAMIE KATZ ’72, BUS’80, JAZZ DIRECTOR, HOST “JAZZ ’TIL MIDNIGHT”: Even before I applied, I’d listen to WKCR. There was a wonderful Sunday night jazz show hosted by George Klabin ’68, “Jazz ’Til Midnight.” I would call in from time to time, ’cause he’d have a contest or something; so I knew him a little by phone. When I got accepted, I called him and he said, “Well, stop by the station and find me.” No sooner have I arrived practically, but he says, “I have to go to Brazil” — he was from there — “why don’t you take over my show?” It’s like, October of my freshman year. Back then there was a bit of an apprenticeship; they put you on the AM station and you worked your way up the minor leagues. But I didn’t have to do any of that. I just had this show all of a sudden.

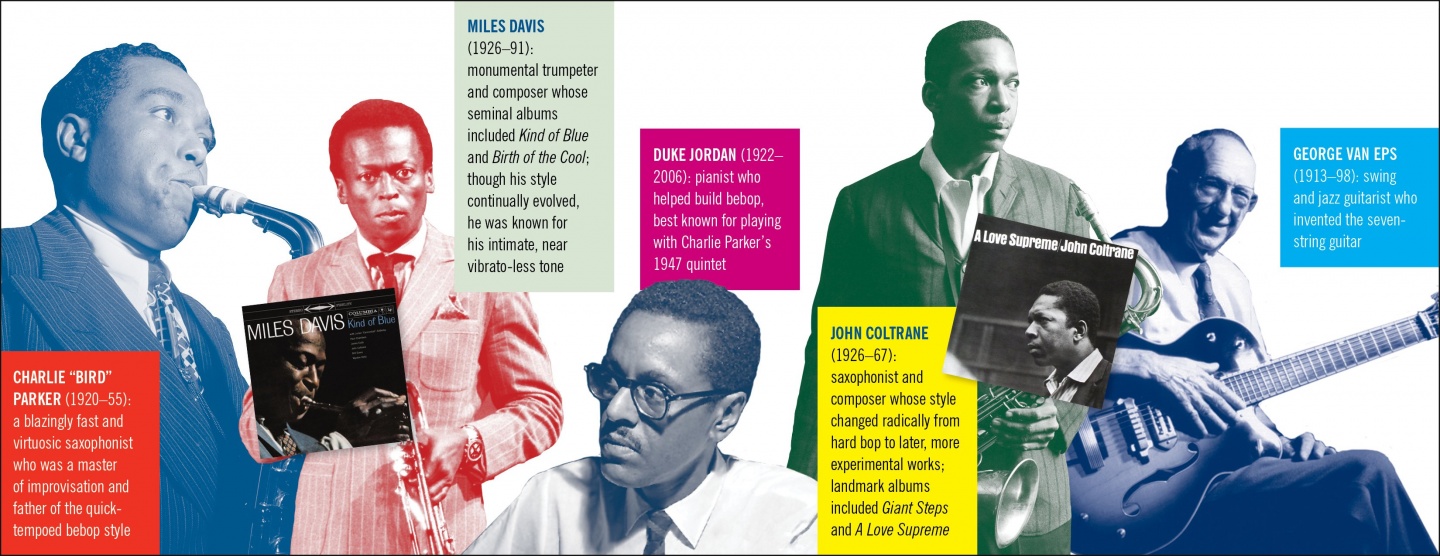

NESI: I played jazz saxophone and clarinet for years, and I was brought up in a family of jazz lovers. My uncle George — George Van Eps, not a blood uncle, but that’s what we called him — invented the seven-string guitar. He was a famous jazz guitarist in the 1930s, ’40s and ’50s. He used to come to our house at Thanksgiving and sit around and play for the family.

KATZ: My father, Dick Katz, was a jazz pianist, composer and sometimes producer. He was my greatest teacher of jazz knowledge. It was important to him that I understand the music — the challenge of it and the difficulty and the craft — all that it takes to be a creative musician and a working professional. So I grew up in that world; there were always musicians around and I went to hear a lot of things and was exposed to a lot of jazz. It seemed as natural as the air we breathe.

NESI: Jamie and I talked often about expanding the programming. We said we should be thinking of jazz — which, after all, is an American art form. We should give it the same credibility and exposure as we give to the Europeans.

KATZ: I thought it was important that Columbia have more of a bond with the community it was adjacent to in Harlem, and the city in general. I felt and continue to feel that jazz is a very important American achievement and a living piece of culture that should not be ignored. I had a bit of an evangelistic bent.

NESI: Of all the jobs I’ve ever held in my life, being program director was certainly the most fun. I didn’t have a boss. I designed the entire radio programming. Though, once somebody got their own show, I didn’t do much except give a helpful nod here and there.

KATZ: When I became jazz director [in fall 1969], I took it very seriously. I thought, the only way we’re going to get more jazz on the air is if I recruit a bunch of really good people and we sort of flood the station. Tom created all these slots across the week. And that’s exactly what we did.

CARROLL, PROGRAM DIRECTOR, HOST “JAZZ PROJECTIONS”: Growing up in northwest Pennsylvania, jazz on the radio was pretty much nonexistent. My introduction came mostly by way of references made by musicians I liked — I’d say,“Who’s this guy Coltrane?” I’d buy a record, check it out, one thing led to another. When I got to New York, I went crazy going to the used record shops and loading up on vinyl.

Most people’s point of entry to WKCR was as an engineer. You’d run the soundboard and do a station break every half-hour. I would do that sometimes for Jamie, then he introduced me to David Reitman ’69, who had a show on Wednesdays. It was quite eclectic; he would play avant-garde jazz, as well as blues, and somewhat obscure R&B. There were a group of us who had these diverse interests and were curious about how they crossed over each other. We began to grow this little group of potential insurgents.

SCHAAP, HOST “JAZZ ALTERNATIVES”: I had been raised by the jazz community; the pioneers of jazz were still alive then, and I had known them from literally infancy. My father was a translator for the French jazz scholars; my mother was a bohemian and a classically trained pianist. Then we moved to Hollis, Queens — that was the bedroom community of jazz. As a young child I knew Lester Young; he died when I was 8, but many others lived well into my adult life and indeed, I brought them all to KCR and did these interviews.

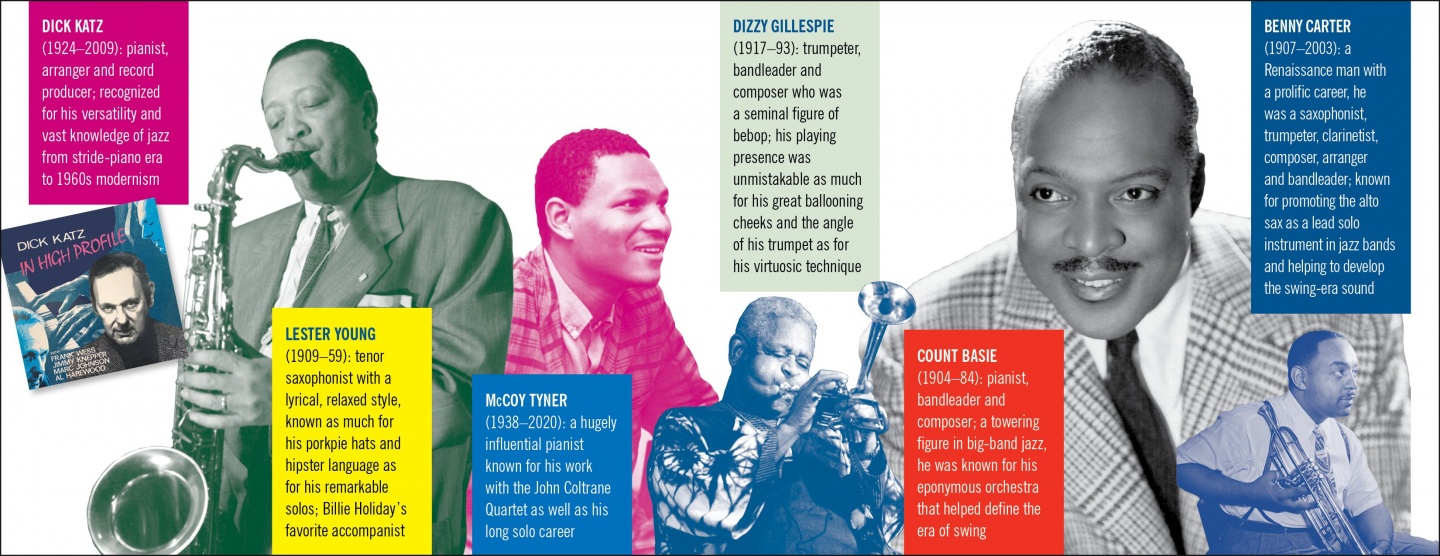

KATZ: I’m in my dorm room on the seventh floor of Furnald. I hear a knock at the door and there’s this tall, friendly guy. He said, “I’m Phil Schaap, I live upstairs and I understand you’re the guy to talk to about jazz at KCR.” We get to talking and he’s very personable and seems to have a great enthusiasm for jazz. I decide to give him a blindfold test; that’s where a musician sits down and I.D.s a record cold. I put on McCoy Tyner at Newport, playing a tune by Dizzy Gillespie called “Woody’n You.”And he immediately got the record.

SCHAAP: He put me through my paces. Then he thought he tricked me by playing Count Basie’s first record, before he developed his leaner style — but I aced that.

KATZ: And another one and another one. Finally, I put on one that I thought might stump him. By a jazz guy named Benny Carter. He gives me the date of the recording; the name of the tune; the entire personnel — including, “and on piano is Richard Aaron Katz.” Nobody knew my father’s full name, not even in the family; nobody called him Richard, it was just on his birth certificate. Phil even said, “Born in Baltimore on March 13, 1924, and in this solo he shows the definite influence of Basie and Ellington and Teddy Wilson,” and I’m of course floored. I said, “I think you’re qualified.”

ABDUS-SALAAM, DIRECTOR OF THE JAZZ DEPARTMENT, HOST “JAZZ ’TIL MIDNIGHT”: When I got to Columbia, I wasn’t thinking about radio. I played football. But after the fall semester, I wanted to find something else to do. Something inside said, “Why don’t you go by the radio station?” So I started coming in, and Jamie said, “Hey man, you ever thought about doing a jazz show?” I said, “No.” He said, “Well, think about it, because I’m going abroad in May.” I took over “Jazz ’Til Midnight” on Sunday nights.

SEIBERT, ENGINEER, HOST “JAZZ ALTERNATIVES”: I told the guy who answered the door at KCR, “I’ll do anything.” He said, “OK, I have a broom, you can sweep the floor.” That was fine with me. Once I decide I want to do something, I’ll do whatever it takes.

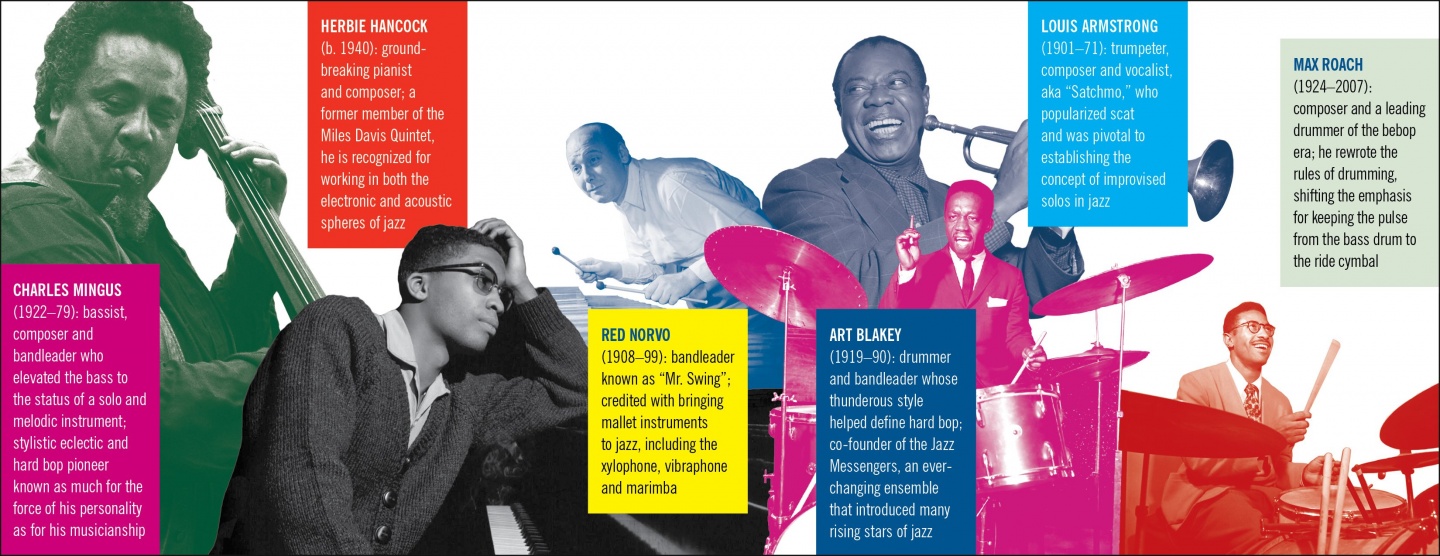

The first engineering role I had was a two-hour shift on Sundays. The first hour was with Jim Carroll, who had an avant-garde jazz show, and my second hour was a calypso show with a guy called Ethan 4. They couldn’t have been more different. Jim’s show was screeching saxophones and noise, as far as I was concerned. Every time I put on a record, I’d turn it down to almost zero so I didn’t have to listen. Ethan’s show was playing all the hits from the islands, Jamaica, St. Maarten or wherever. I’d been doing that for several months, and then one day I went to see a band of former jazz musicians playing what became known as fusion. I walked away transformed. The next day, I went to engineer Jim’s show, and the music made sense to me. Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman, John Coltrane, Cecil Taylor — all of a sudden I could hear the music for the first time.

KATZ: By 1970, we had a lot of people working on a lot of shows. Once Phil and the next group took over, they never let go.

SCHAAP: In the week preceding classes in September 1970, there was a meeting of the people of KCR. It became clear that we could create something, on our own initiative, that would be broadcast to New York City and the metropolitan region. To use a modern term that people didn’t really use in those days — this was an “opportunity.”

ABDUS-SALAAM: A spot on the FM dial in New York was important.

SEIBERT: I think there were 78 radio stations in the city at the time.

SCHAAP: We decided to pursue alternative programming — we were going to present culture, primarily music, that had no commercial following; music that we thought needed to be heard.

CARROLL: We had the opportunity to fill in some big holes.

ABDUS-SALAAM: We wanted to be the most non-college, college radio station that existed. We had an AM and an FM station; the AM station was just for the dorms. So students who just wanted to play around, to play rock and stuff, could do it and have fun.

CARROLL: This was an opportunity to get some music out there that was emanating from communities that were not well served by New York broadcasting, the Black community in particular.

SCHAAP: There was an understanding of jazz’s importance, its connection to the African-American experience. Commercial radio had abandoned jazz. Somebody said, “Jimi Hendrix doesn’t need us. Duke Ellington and Ornette Coleman do.”

SEIBERT: We needed to take a strong stance that jazz was the preeminent musical expression of its time, and that we needed to be the standard bearer for it. We had the loudest mouths in the place. I think that’s what it came down to. We sort of took over.

SCHAAP: We did our first marathon festival that fall, for Albert Ayler. One show for a couple of hours is easy to miss; but this would be distinct, it was more time for people to find out about us. Who else could have done 24 hours on Albert Ayler? There was no NPR; PBS was in its infancy. He’s not even going to get a mention — “Albert Ayler died today” — on 1010 WINS. The marathon programming seemed a way of making a bigger splash. It also seemed more dignified and reverent. [At that time] there wasn’t a lot of reverence for this remarkable addition to the American experience, and this African-American contribution to the American experience.

CARROLL: In 1971, I was fortunate in being chosen program director. We went to a schedule with about 40 percent each of jazz and classical. The rest was a combination of folk, blues and country, and the international music shows.

ABDUS-SALAAM: As the jazz department grew, musicians began to realize this would be a venue for people to hear their music. The first phone call I received was from a bassist, Reggie Workman. At the time he had just come off from playing with Coltrane for a number of years. He called me because he was working with some other musicians, I think based in Brooklyn, and he heard our jazz on the radio. He introduced himself and what he was all about, and said, “Man, I’m so glad to hear you’re on the air.”

SEIBERT: The only other station in the marketplace that was playing jazz with any regularity was WRVR, up at Riverside Church, and they only paid attention to the most mainstream musicians.

ABDUS-SALAAM: Because we were non-commercial, we didn’t have to worry about what sponsors might say — “We don’t like that music, or that’s too far out.” They basically left us alone.

CARROLL: We had a significant renovation of Studio A, which became the primary studio for recordings and live music broadcasts. With the improvement of the acoustics and a new mixing board, it became a very viable facility.

SEIBERT: One night, David Reitman invited an actual group of jazz performers to play live on his show, and nobody wanted to engineer it. I was like, “Oh, I’m in, I’ll do that.” The booth couldn’t have been more than 12 ft. by 12 ft. And we threw in a drummer, a vibraphonist, a trumpeter, a bassist and an alto saxophone. I was in heaven. David at this point was a professional working for music magazines, and he started inviting musicians regularly to perform. That encouraged other people to invite musicians to their shows. And, very quickly, jazz musicians were floating in and out of the place.

ABDUS-SALAAM: Schaap was my go-to sound guy. I said, “Phil, I have all these musicians coming up and we want to do a live broadcast.” The band was Moudon Peace Excursion.

SCHAAP: I get there and they had 26 musicians! It was insane, there wasn’t a room that could have held them at the station, even without their instruments. I had to go into Furnald and start knocking on doors, asking if people had transistor radios with batteries, and could I borrow them? In the end I broke them into three separate rooms and wired them all to go live on the air. I’m still proud of it.

SEIBERT: We were bringing all of these what I’ll loosely call either up-and-comers, or ignored musicians because they were avant-garde musicians, more free jazz stylists than the mainstream. Those are the people who were eager for attention.

CARROLL: They had found a lot of doors closed in their faces. Publicity at that point [was a challenge]. If you couldn’t get on the radio, the options were live performance and getting your recordings into record stores. In New York you had little specialty shops down in the Village, but if you walked into Sears, you weren’t going to find a lot of cutting-edge jazz recordings. The word got out that WKCR was a place your music could be heard, and where you would be treated respectfully by people who were really interested in what you were doing.

SEIBERT: Then the musicians themselves started telling each other. So when you called a musician and asked them to perform, they were like “OK, that’s home for me. That’s a place where I can belong and they will take care of me on some level. Village Vanguard won’t give me a venue, Birdland won’t give me a venue, but these people will.”

ABDUS-SALAAM: We did a lot of live broadcasts in the studio, and I learned a lot from conversations with musicians. That’s one of the reasons we did interviews, so people could get first-hand information. That’s how we tried to grow the knowledge of this music.

SCHAAP: Sharif and Vernon Gibbs ’74 interviewed Charles Mingus in 1972, that was a very momentous thing.

GIBBS, HOST “BLACK MUSIC HAPPENINGS”: In high school I’d started writing about music for Rock magazine and other underground publications, going down to the Village and being part of that scene. On my show I would play the complete spectrum of Black music. I liked pretty straight-ahead jazz — I was more of a Herbie Hancock fan, more of a Miles Davis fan. But I was aware of Mingus’s importance. And he was married to the publisher of one of the rock publications that I wrote for, so I was able to get him to agree to an interview.

ABDUS-SALAAM: Mingus had a reputation for being somewhat gruff. He wouldn’t take no mess. So here we are, these two young kids, 18 or 19. He was a little late getting to the station and when we sat him down, he didn’t want to be there. You could absolutely tell he didn’t want to be bothered. We started asking questions and he gave one-word answers. After a while we put some music on and he said, “Wait a minute, is that me playing with Red Norvo?” I said, “Yes, it is.” And he said, “Take that shit off, because he never paid me!”

Once again, I’m thinking about Mingus’s reputation — what am I supposed to do? I took the needle off the record. Then he looked at us and said, “Hey, you kids are alright.” And we did a two- or three-hour interview. We had a ball, he started telling stories. We had a wonderful session.

GIBBS: I don’t remember him being contentious or a problem. He was polite, he answered questions directly. I remember him being a very well thought-out interview.

ABDUS-SALAAM: Art Blakey, Max Roach, Ornette Coleman — the list [of people we interviewed] goes on and on. Monster musicians. Miles Davis never made it to the station, but basically everyone else who was on the scene then came through.

CARROLL: There was a great deal of collaboration, that was one of the wonderful things. We’d throw ideas around; occasionally you’d get into a somewhat heated argument over something. It was very educational, as well as damn interesting.

SEIBERT: I never went to class. To this day I have not graduated — I majored in WKCR.

ABDUS-SALAAM: Everyone was focused toward putting out some great music on the airwaves; nobody was there for an ego trip, nobody was trying to become a radio personality. It was the right people in the right place at the right time, having the opportunity to do what we were able to do.

GIBBS: We were happy to be in our situation, happy to help the musicians. And we were happy to be part of the story of keeping jazz as, and recognizing it as, a form of classical music. That was our angle, and KCR helped us — everyone who played the music and loved the music that they played — to tell that story.

SCHAAP: On July 4, 1971, one of the listeners to the Louis Armstrong birthday broadcast was Louis Armstrong. His neighbor Selma Heraldo told me. He was bringing his stereo on a dolly out to the garden of his house in Queens. And she said, “You don’t have to do all that, just put a radio up on the garden wall. They’re playing your music around the clock.” He turned us on and there we were.

Interviews have been condensed and edited for clarity. Ben Ratliff ’90 and Jim Gardner ’70 (né James Goldman) also contributed to this story.

Their Favorite Things

WKCR music men share the jazz tunes they love: college.columbia.edu/cct/ latest/feature-extra/WKCR

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu