Monks are supposed to live in isolation and silence. Not so Thomas Merton ’38, GSAS’39. When he died 50 years ago in December, he was so well known that the news made the front page of The New York Times.

Monks are supposed to live in isolation and silence. Not so Thomas Merton ’38, GSAS’39. When he died 50 years ago in December, he was so well known that the news made the front page of The New York Times.

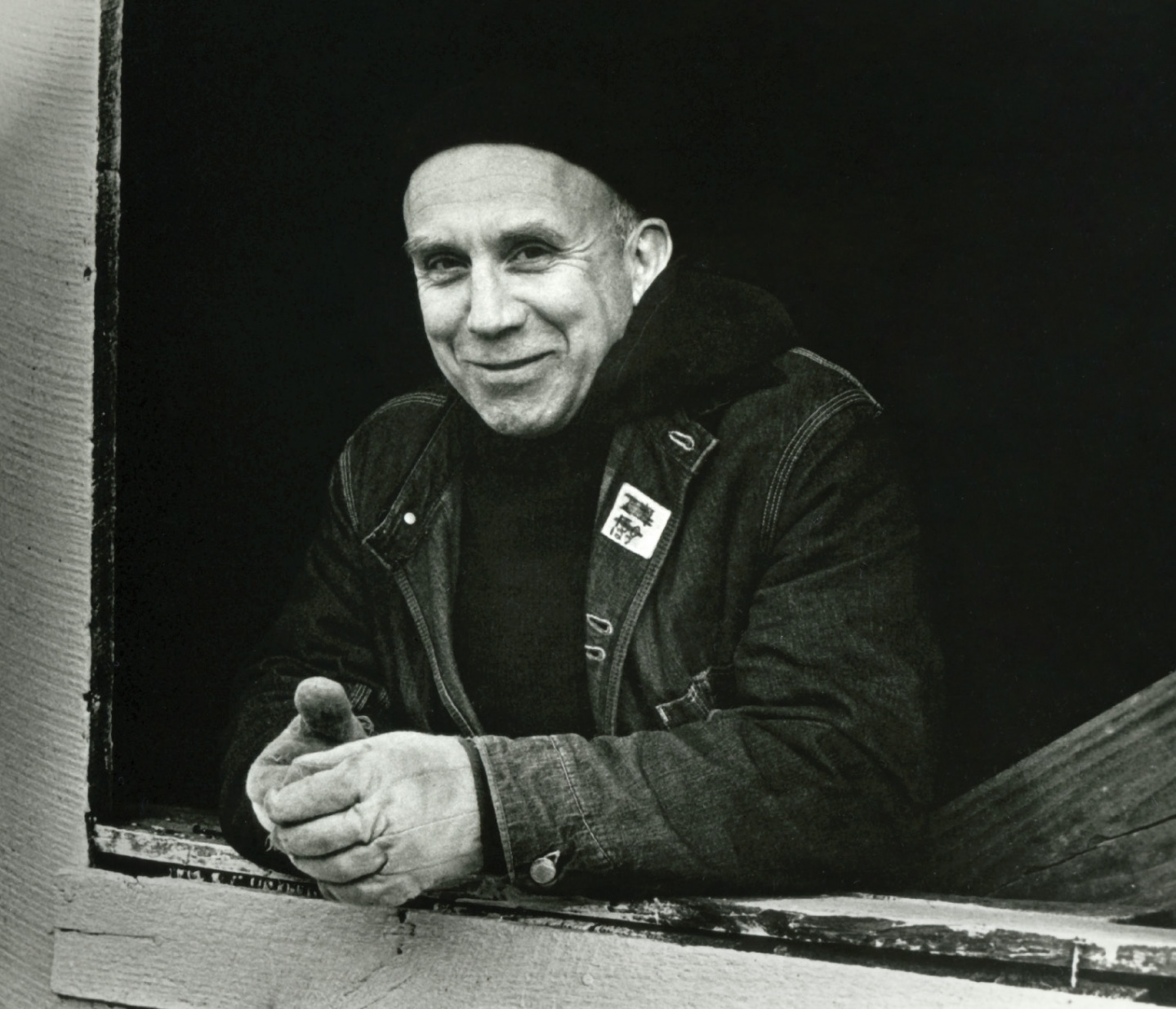

Edward Rice ’40

Monks are supposed to live in isolation and silence. Not so Thomas Merton ’38, GSAS’39. When he died 50 years ago in December, he was so well known that the news made the front page of The New York Times.

Today, Merton remains the world’s worldliest hermit. From within his rural Kentucky monastery, he issued dozens of volumes of letters, journals, essays, translations, reflections and verse. These books, many published posthumously, have canonized him as both a leading Christian thinker and a bridge builder across faiths. Their very titles (Dancing in the Water of Life, Emblems of a Season of Fury, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander) evoke a restless conscience. For those who have ever wondered how to serve both God and Caesar, or struggled to reconcile religions, Merton remains a guide.

Merton (his priestly name was Father Louis) was a unique penitent. As both adolescent and grown-up, he had one foot in the godly realm and another in secular — even sinning — society. On campus, he drew cartoons for Jester, wrote for the Columbia Review, joined Philolexian and crashed on the couch at Alpha Delta Phi. Off campus, he frequented jazz clubs and flirted with communism.

But all the while, Merton was aspiring to grace. He was 18 when, he recalled, “I first saw Him.” And as civilization hurtled toward total war, he increasingly embraced Him. In November 1938 he had himself baptized at Corpus Christi Church on West 121st Street, just behind Teachers College. A week after Pearl Harbor, he entered the Abbey of Our Lady of Gethsemani, 50 miles southeast of Louisville, to join the Trappists. “I don’t think we’ll ever hear from Tom again,” his mentor, Mark Van Doren GSAS 1921, said ruefully.

Far from it. In 1948, after an attempt at censorship by one of his monastic superiors, Merton published a memoir, The Seven Storey Mountain. He told of a child born in France during WWI — one who was raised there, in England and in New York. He told of a fragmented family. And he told of an awakening that culminated in a permanent home in “the four walls of my new freedom.”

The Seven Storey Mountain was a surprise bestseller and inspired many who were looking for heavenly guidance during the early Cold War. It spurred a bevy of readers to check out the monastic life, and it helped demystify Catholicism for a pre-Vatican II America that still regarded the Church of Rome with suspicion. Merton’s friend and editor at Harcourt Brace, Robert Giroux ’36, noted that another sign of the book’s impact was the resentment it provoked among those who thought it inappropriate for any monk to write. Of the negative mail that poured into his office, Giroux recalled in 1998, “I had a short answer for the hatemongers: ‘Writing is a form of contemplation.’”

From then on, Merton neither would nor could be immured. His increasing renown posed an existential dilemma. Merton had sought attention, yet he could not wholly abandon his ascetic discipline. In that double-edged regard, said the writer Edward Rice ’40, Merton’s friend, and sponsor and godfather at his baptism, “His entire life was a search, one that led him further and further into the inner — and outer — reaches of the human mind and soul.”

That search expanded as issues of race, peace and especially holiness of all kinds preoccupied him in the 1950s and ’60s. “I am trying to figure out some way I can get nationalized as a Negro,” Merton told another College friend, the minimalist poet Robert Lax ’38, “as I am tired of belonging to the humiliating white race.” To the Pakistani Sufi master Abdul Aziz he wrote, “I would like to join spiritually with the Moslem world in this act of love, faith and obedience toward Him Whose greatness and mercy surround us at all times.” As war in Southeast Asia began making headlines, and monks on the other side of the globe began setting themselves on fire, he intensely explored Zen Buddhism in relation to the West.

When Pope Francis addressed a joint session of Congress in 2015, he cited four Americans who, he said, had succeeded in “seeing and interpreting reality” — Dorothy Day, Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr. ... and Merton.

Ultimately, Gethsemani proved too small for Merton. He acquired his own hermitage on the grounds; there he received visitors ranging from old Columbia cronies to the folk singer Joan Baez. Correspondence arrived from Evelyn Waugh, the cranky author of Brideshead Revisited, and the future Nobel Prize winner in literature Czeslaw Milosz. He traveled within the United States and even abroad, meeting three times with the Dalai Lama.

Merton’s death on December 10, 1968, was mysterious, even bizarre. Following a session at a religious conference in Bangkok (“I will disappear from view and we can all have a Coke or something,” he said by way of adjourning), he apparently took a shower, slipped on the floor, grabbed an upright fan for balance and electrocuted himself. He was 53.

Ten years later, Columbia Catholic Ministry inaugurated its annual Thomas Merton Lecture, funded by the Hugh J. [’26] and Catherine R. Kelly Endowment. This past spring, a $100,000 gift in memory of Edmund J. Kelly LAW’62 was made toward the lectures.

Merton’s journals from 1964 and 1965 were published as A Vow of Conversation. It is a vow he has kept.

— Thomas Vinciguerra CC’85, JRN’86, GSAS’90

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu