Editor Robert Gottlieb ’52 recounts his collaboration with Joseph Heller GSAS’50 on the satirical novel Catch-22. (Spoiler alert: It was originally titled Catch-18!)

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Editor Robert Gottlieb ’52 recounts his collaboration with Joseph Heller GSAS’50 on the satirical novel Catch-22. (Spoiler alert: It was originally titled Catch-18!)

“For a long time when people asked me whether I was ever going to write a memoir or autobiography, I answered that all editors’ memoirs basically come down to the same thing: ‘So I said to him, “Leo! Don’t just do war! Do peace too!”’”

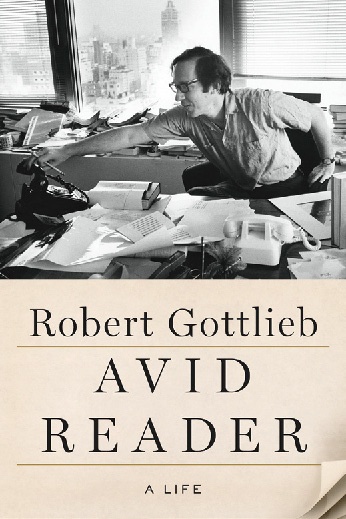

This astute, down-to-earth remark, which opens Robert Gottlieb ’52’s memoir, Avid Reader: A Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $28), helps a literary outsider understand why so many of the 20th century’s prominent authors chose to work with him. During his storied, decades-long career as a top book editor (from 1955 to the present), Gottlieb collaborated with Toni Morrison, John le Carré and Robert Caro, among many others. He also pulled off the publishing professional’s equivalent of a Triple Crown win, by serving as editor in chief at two top publishing houses — Simon & Schuster and Alfred A. Knopf — and then leaving to helm The New Yorker (from 1987 to 1992).

Avid Reader follows Gottlieb through his early days as a College student (and editor of the influential Columbia Review) to his current role as Knopf editor, book author and contributor to The New York Review of Books and other publications. The resulting narrative is, as Esquire puts it, “a master class in how modern literature gets made.”

Here, Gottlieb describes the making of one contemporary classic, Joseph Heller GSAS’50’s novel CATCH-22.

— Rose Kernochan BC’82

The literary agent Candida Donadio and I were only about a year apart in age, and almost instantly we became close, despite the radical difference in our backgrounds and temperaments. Candida was Sicilian, as she liked to boast — particularly about her taste for Sicilian cold revenge. She was short, plump, matronly, and always swathed in black — a figure from post-war Italian neo-realist film. Her deep voice was often filled with doom and anguish — “The children! The children!” she liked to cry, literally thumping her ample bosom. She herself had no children, but as Michael Korda was to write, “All writers were like children, but her writers were her children. She felt about them as if she were their mother.”

MIKE LOVETT

Our alliance, as it was thought of in our little world, would in the mid-sixties be officially cemented by Esquire, which named the two of us the “red-hot center” of the publishing world — momentarily gratifying but far from the way we saw ourselves. What connected us wasn’t ambition or the hope of public notice but the fact that we were obsessive readers whose tastes were highly similar, and our bedrock belief that writers came first.

Candida lived in a tiny apartment a few blocks from our floor-through in a dilapidated brownstone on Second Avenue in the Fifties — we had a blue-painted floor and there were old-fashioned fire escapes front and back. If she was sick, either my wife, Muriel, or I would carry over homemade chicken soup, while if we had an emergency babysitting crisis, she would pad over in her sneakers and take care of little Roger. We shared our problems, or as my great friend Irene Mayer Selznick liked to say, we “took in each other’s washing.”

On August 29, 1957, Candida sent me a note that read, “Here is the ’script of CATCH 18 by Joseph Heller about which we talked yesterday. I’ve been watching Heller ever since the publication of Chapter 1 in New World Writing about a year ago. He’s published a good bit in The Atlantic Monthly, Esquire, etc. I’ll tell you more about him when I see you at lunch next week. As ever, Candida.”

About seventy-five pages of manuscript came with it, and I was knocked out by the voice, the humor, the anger. We offered Joe five hundred dollars as an option payment, but Joe and Candida decided to wait until there was enough of a manuscript to warrant an actual contract.

When I met Joe for the first time, for lunch at a hearty restaurant near our offices, he came as a big surprise. I expected a funny guy full of spark and ginger, but what I got was more or less a man in a gray flannel suit — he was working as an ad executive at McCall’s, and he looked it. And sounded it. I found him wary (which shouldn’t have been a surprise, given the paranoid slant of much of his book), noncommittal, clearly giving me the once-over. He told me later he found me nervous and ridiculously young. I was only eight years younger than he was, but he was a mature ex-vet, a former college teacher, and a successful business executive. I was twenty-six, still looking much younger than I was, and with no track record as an editor or publisher — this was well before The American Way of Death, The Best of Everything, The Chosen, et al. So it wasn’t love at first sight. But it proved to be something a lot more substantial: a professional and personal relationship that never faltered, despite gaps in our publishing together, and despite (or because of?) the fact that through the more than forty years we worked with each other on and off, we rarely saw each other socially. As with Decca Mitford and Chaim Potok, there was never a disagreeable word between us, and there was always complete trust. I certainly always knew that I could turn to him in need, and I know he felt the same way about me. Indeed, there would be dark moments ahead in our personal lives — usually involving our children — which proved it.

The most significant trust was editorial. Once his book was completed, three or so years after we first met, I tore into it — relaxed about doing so because I had no notion that I was dealing with what would turn out to be sacred text. Or that Joe would turn out to be as talented an editor as he was a writer, and absolutely without writer ego. On Catch, as with all the other books we worked on together, he was sharp, tireless, and ruthless (with himself), whether we were dealing with a word, a sentence, a passage of dialogue, or a scene. We labored like two surgeons poised over a patient under anesthesia.

“This isn’t working here.”

“What if we move it there?”

“No, better to cut.”

“Yes, but then we have to change this.”

“Like this?”

“No, like that.”

“Perfect!”

Either of us could have been either voice in this exchange. I wasn’t experienced enough back then to realize how rare his total lack of defensiveness was, particularly since there was never a doubt in his mind of how extraordinary his book was, and that we were making literary history. Even when at the last minute, shortly before we went to press, I told him I had always disliked an entire phantasmagorical chapter — for me, it was a bravura piece of writing that broke the book’s tone — and wanted to drop it, he agreed without a moment’s hesitation. (Years later, he published it in Esquire.) Where my certainty came from I don’t know, but although I mistrusted myself in many areas of life, I never mistrusted my judgment as a reader.

“I felt then, and still do, that readers shouldn’t be made aware of editorial interventions; they have a right to feel that what they’re reading comes direct from the author to them.”

Joe was so eager to give me credit that I had to call him one morning, after reading an interview with him in the Times, to tell him to cut it out. I felt then, and still do, that readers shouldn’t be made aware of editorial interventions; they have a right to feel that what they’re reading comes direct from the author to them. But enough time has gone by that I don’t think any harm will be done if I indulge myself by repeating what Joe’s daughter, Erica, wrote in her uncompromising memoir, Yossarian Slept Here: “My father and Bob had real camaraderie and shared an almost mystical respect. No ego was involved, regardless of where Bob’s pencil flew or what he suggested deleting, moving, rewriting. To Dad, every word or stroke of this editor’s pencil was sacrosanct.” Even if this is friendly overstatement, and it is, it reflects the reality of our dealings with each other.

Not that there weren’t stumbling blocks along Catch’s path to publication. First of all, when the finished manuscript came in there were colleagues who disliked it intensely — they found it coarse, and they saw the repetitions in the text as carelessness rather than as a central aspect of what Joe was trying to do. Then we had a copy editor who was literal-minded and tone-deaf. Her many serious transgressions included the strong exception she took to Joe’s frequent, and very deliberate, use of a string of three adjectives to qualify a noun. Without asking me, she struck out every third adjective throughout. Yes, everything she did was undone, but those were pre-computer days: It all had to be undone by hand, and it wasted weeks.

But the biggest catch on the way to Catch’s publication was the title. Through the seven or so years that Joe worked on his book, including the four during which he and Candida and I grew more and more attached to it, its name was Catch-18. Then, in the spring 1961 issue of Publishers Weekly that announced each publisher’s fall books, we saw that the new novel by Leon Uris, whose Exodus had recently been a phenomenal success, was titled Mila 18. They had stolen our number! Today, it sounds far from traumatic, but in that moment it was beyond trauma, it was tragedy. Obviously, “18” had to go. But what could replace it?

There was a moment when “11” was seriously considered, but it was turned down because of the current movie Ocean’s 11. Then Joe came up with “14,” but I thought it was flavorless and rejected it. And time was growing short. One night lying in bed, gnawing at the problem, I had a revelation. Early the next morning I called Joe and burst out, “Joe, I’ve got it! Twenty-two! It’s even funnier than eighteen!” Obviously the notion that one number was funnier than another number was a classic example of self-delusion, but we wanted to be deluded.

To talk of a “campaign” for Catch-22 is to put a label on something that didn’t exist. There was no marketing plan, no budget: Nina Bourne — who was the brilliant advertising manager at S & S and my closest collaborator and friend there — and I just did what occurred to us from day to day, spending our energies (and S & S’s money) with happy abandon. We began with little teaser ads in the daily Times featuring the crooked little dangling airman that the most accomplished designer of his time, Paul Bacon, had come up with as the logo for the jacket. We had sent out scores of advance copies of the book, accompanied by what Nina called her “demented governess letters” — as in, “the demented governess who believes the baby is her own.” Almost at once, excited praise started pouring in. Particularly gratifying to Joe was a telegram from Art Buchwald in Paris:

PLEASE CONGRATULATE JOSEPH HELLER ON

MASTERPIECE

CATCH 22 STOP I THINK IT IS ONE OF THE

GREATEST

WAR BOOKS STOP SO DO IRWIN SHAW AND

JAMES JONES.

The range of early admirers was astonishingly broad, from Nelson Algren (“The best American novel that has come out of anywhere in years”) to Harper Lee (“Catch-22 is the only war novel I’ve ever read that makes any sense”) to Norman Podhoretz [’50](!). There were at least a score of letters from notable writers, but, perversely, the one we most enjoyed was from Evelyn Waugh:

Dear Miss Bourne:

Thank you for sending me Catch-22. I am sorry that the book fascinates you so much. It has many passages quite unsuitable to a lady’s reading. It suffers not only from indelicacy but from prolixity. It should be cut by about a half. In particular the activities of ‘Milo’ should be eliminated or greatly reduced.

You are mistaken in calling it a novel. It is a collection of sketches — often repetitive — totally without structure.

Much of the dialogue is funny.

You may quote me as saying: “This exposure of the corruption, cowardice and incivility of American officers will outrage all friends of your country (such as myself) and greatly comfort your enemies.”

Yours truly,

Evelyn Waugh

We didn’t take him up on his offer, though we probably should have.

Reviews were mixed, veering from ecstatic to vicious, but the success of the book built and built. It was slow, though — never strong enough at any one moment to place it on the bestseller list, yet sending us back to press again and again for modest printings. Meanwhile, Nina and I unleashed a series of ads that just occurred to us as things happened, all of them rehearsing the ever-swelling praise from critics, booksellers, academics, and just plain book-buyers: We had enclosed postage-paid cards in thousands of copies and got hundreds of responses, positive (“Hilarious”; “Zany”) and negative (“A complete waste of time”; “If everyone in Air Force was crazy — How did we win war?”). Many of those who loved it were demented governesses in the Nina mold, like the college instructor who wrote,

“At first I wouldn’t go into the next room without it. Then I wouldn’t go outside without it. I read it everywhere — on the buses, subways, grocery lines. If I did leave it out of my sight for a moment, I panicked . . . until last night I finally finished it and burst out crying. I don’t think I’ll ever recover . . . But before I die of Catch-22, I will do everything to keep it alive. I will change ads on subways to “Promise her anything but give her Catch-22.” I’ll write Catch-22 on every surface I can find. I’ll pirate and organize a Catch-22 Freedom Bus . . . I’m a happier person today for Catch-22. Happier, sadder, crazier, saner, better, wiser, braver. Just for knowing it exists. Thank you.”

Comparable if less rhapsodic communications poured in from a put-and-call broker, a New Jersey die-casting manufacturer, a New York grandmother, a fifteen-year-old boy from Eugene, Oregon, a housewife (“I am now getting phone calls in the middle of the night from people I’ve given the book to who want to read him aloud to me!”) It was this kind of unbridled enthusiasm that sealed Joe’s success — the impulse of his readers to keep the ball rolling. (A well-known example was the concocting of thousands of “Yossarian Lives” stickers by the NBC anchorman John Chancellor, which blossomed on campuses and public buildings everywhere. Another fan came up with, and widely distributed, “Better Yossarian than Rotarian” stickers.) Catch, indeed, swept college students up with its challenges to authority and the establishment; again and again commentators compared its influence on young people to that of The Catcher in the Rye and Lord of the Flies.

Robert Gottlieb ’52

RICHARD OVERSTREET

Because Catch became such a phenomenon, because the work Nina and I did to sell it was so highly visible and remarked upon in the publishing world, and because Joe never stopped talking about what he saw as my crucial role in editing it, I became highly visible myself — it’s still the book I’m most closely associated with among the kind of people who think about such things. But in the years that followed its publication, I more or less put it out of my mind. I certainly never reread it — I was afraid I wouldn’t love it as much as I once had. Even so, when in 2011 its fiftieth anniversary was being widely celebrated, I agreed to take part in the celebrations.

But there was a catch: Catch-22.

There was no way I could talk about it without reading it again. It was a big relief to find that I still did love it, that Nina and Candida and I — and Joe — and the world — hadn’t been misguided in our passion for it. I was bowled over once again by the brilliance of the construction, the exhilaration of the writing, the humor (of course), but also by the bleakness of Joe’s vision of life. To me, Catch-22 was always more tragic than comic — a judgment confirmed by his magnificent second novel, Something Happened, which came along eight years later. There was certainly nothing funny about it!

Excerpted from AVID READER: A LIFE, by Robert Gottlieb, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Robert Gottlieb. All rights reserved.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu