Raymond M. Brown ’69 grew up in a segregated housing project in Jersey City, N.J., where his father, Raymond A. Brown, was a well-known civil rights leader and defense attorney. “My father was very militant, what we used to call in the old days a ‘race man,’” Brown says. He remembers his dad saying, amidst the war in Vietnam and campus movements of the late 1960s, “I oppose this war, but you will rue the day you ran Lyndon Johnson out of office.” Brown adds, “He proved to be prophetic about that.”

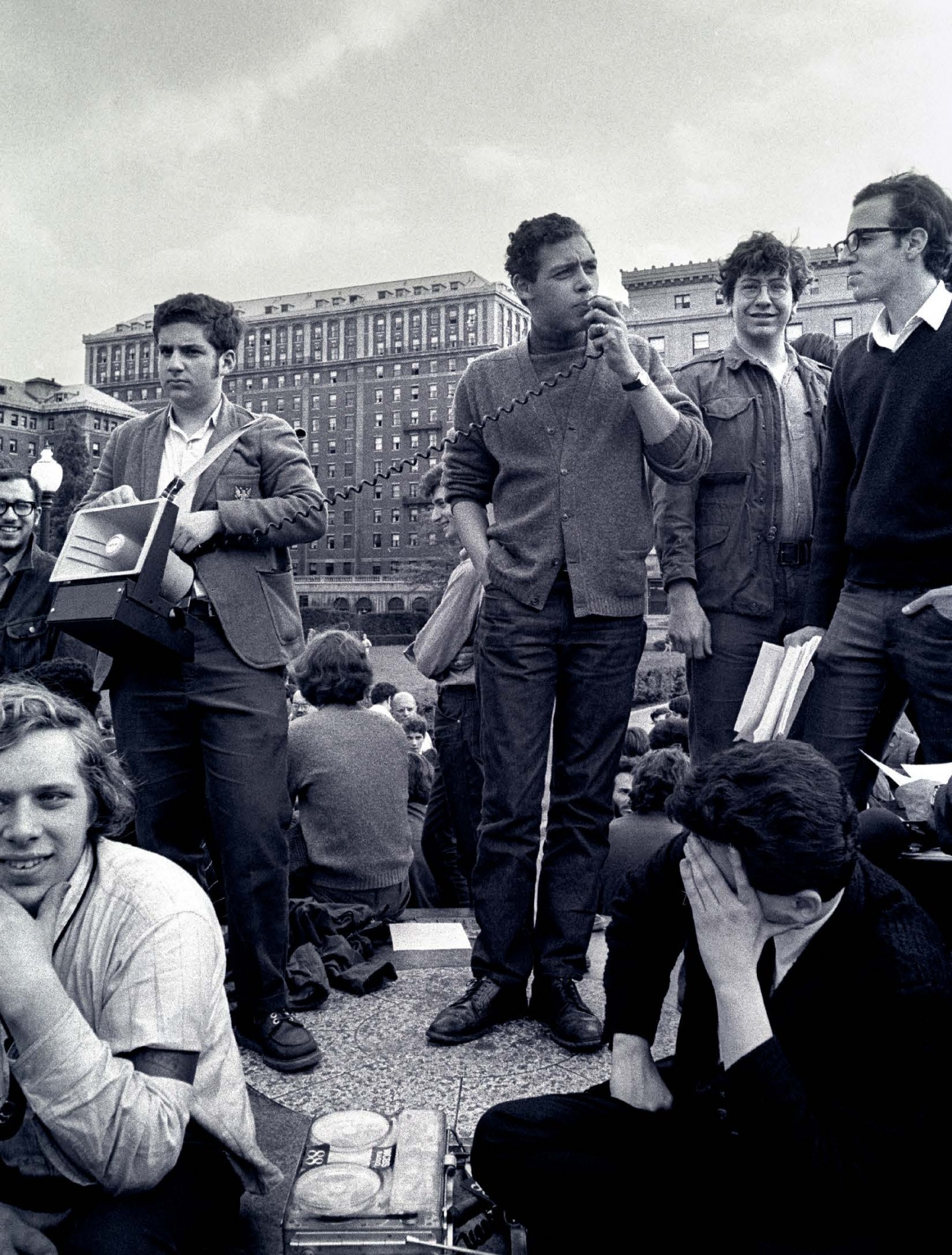

Brown was a leader in the Students’ Afro-American Society (SAS), a key activist group — along with Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) — in the April 1968 student uprising at Columbia. He was arrested when police cleared the campus after the weeklong protests, and was arrested again and beaten on May 22 during a second clash with police on campus. Those experiences piqued his interest in a legal career; eventually Brown followed in his father’s footsteps as a criminal defense attorney.

Most accounts of the ’68 revolt stress the role of Columbia’s SDS chapter and its leader, Mark Rudd ’69. This emphasis has long bothered Brown, not because he seeks the limelight, but because he believes it fails to acknowledge the black students’ occupation of Hamilton Hall as the pivotal event of the protest, not an “ancillary coda to a New Left uprising,” he says.

Brown says people often ask him, “Do you know Mark Rudd?” “For years I found this inquiry irksome, until the past decade, when I bantered with Rudd about it,” Brown writes in A Time to Stir: Columbia ’68, a new anthology of essays edited by Paul Cronin JRN’14. “He has had the grace and insight to supply a proposed answer: ‘Ask Mark Rudd if he knew about the Black Students of Hamilton Hall.’”

There’s much to be said for Brown’s contention. Yes, opposition to the Vietnam War was formidable at Columbia and nationwide by 1968, gaining momentum after the Tet Offensive earlier that year and the entry of antiwar senators Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy into the presidential race. The role of SDS in pushing for more confrontational tactics is undeniable. But the blowup at Columbia was different: It took place on the edge of an angry Harlem community less than three weeks after the shocking murder of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The authorities knew they had to tread carefully. “There was a deep concern that if there were a violent exchange between police and black students at Columbia, there would be a riot in Harlem, and that the city would explode,” says Robert Siegel ’68, the recently retired senior host of NPR’s All Things Considered, who anchored WKCR’s award-winning coverage of the campus uprising. “The white students had no such leverage.”

Finally, the chief impetus for the black students’ involvement was not the war — though SAS joined SDS in opposing Columbia’s ties to war research through the Pentagon-affiliated Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA) — but rather the proposed University gym in Morningside Park, that sliver of contested turf one block east of the campus.

Viewed from the low-lying streets of West Harlem, the cliffs of Morningside Park loom like the walls of a fortress. The rocky bluff actually did play that role once: During the War of 1812, College students and alumni trekked uptown to construct defensive blockhouses along the ridge in case British redcoats invaded the area again, as they had during the Battle of Harlem Heights in 1776. A few generations later, landscape architects Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux transformed this terrain into a picturesque city park that opened in 1895, just a year before Columbia crowned the Heights with its new uptown campus. By the 1960s, however, the park had become a crime-ridden, garbage-strewn buffer zone between a proud but struggling black community and the more privileged precincts above. Freshmen entering the all-male, nearly all-white College in those days were cautioned to switch to the uptown local train at Broadway and 96th Street, lest they wind up at the “wrong” 116th Street station east of the park.

The West Harlem community had a different perspective on Morningside Park’s ballfields, playgrounds and walkways, especially after Columbia conceived a plan to replace its aging, dysfunctional gymnasium with a much larger structure nestled in the park, reserving a small portion for the public. The project drew little attention in the early ’60s, while plans were still on the drawing board, but by 1966–67, opposition was taking hold, and NYC Parks Commissioner Thomas Hoving sharply criticized the surrender of city parkland and the paltry provision for community residents.

Whatever its merits, the gym project presented a perfect emblem — or caricature — of The Man: a powerful white institution imposing its will on the black community while offering limited access to a separate-but-unequal facility. Worst of all, in symbolic terms, the building’s main entrance would command the top of the building, with the community entrance 11 stories below on the Harlem end. A back door, basically. As in, Service Entrance. On one level, this was merely an accident of the park’s topography. On another, it was an intolerable insult.

At the same time, the University was under fire for buying up local real estate and evicting poor tenants to make way for its own expansion. Community relations were at a nadir. “Columbia was not beloved as a landlord and it wasn’t beloved as a neighbor,” Brown says.

The gym project presented a perfect emblem — or caricature — of “The Man”: a powerful white institution imposing its will on the black community while offering limited access to a separate-but-unequal facility.

He and many other black students felt an imperative to align with local activists on these issues, and they formed strong bonds. There were problems on campus, too. Black students were routinely challenged to produce ID at the main gates. When the May 1967 issue of Jester lampooned black frat brothers at Omega Phi Psi as “tar babies” and “a bunch of big ants in purple beanies,” the brothers were not amused. A group marched over to the humor magazine’s office to confiscate several boxes of the offending issue and torched a small stack in front of Ferris Booth Hall. That summer urban riots rocked America; to quell the most violent rebellion, in Detroit, President Johnson dispatched the Army’s 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, which had spearheaded the D-Day invasion 23 years earlier. America was again at war — in Southeast Asia, and increasingly, in its own cities.

In the months leading up to the Spring ’68 crisis, State Senator Basil A. Paterson, Assemblyman Charles Rangel and other local leaders warned Columbia to halt the gym plans. Others took a less civil tone. “If they build the first story, blow it up,” black power advocate H. Rap Brown exhorted community members at a December 1967 meeting of the West Harlem Morningside Park Committee. “If they sneak back at night and build three stories, burn it down. And if they get nine stories built, it’s yours. Take it over, and maybe we’ll let them in on the weekends.”

After King’s assassination on April 4, 1968, mayhem broke out in well over 100 cities. Some 20,000 people were arrested. Fires raged just two blocks from the White House. From Morningside Drive, Columbia could hear the not-too-distant wail of fire engines and police sirens in Harlem.

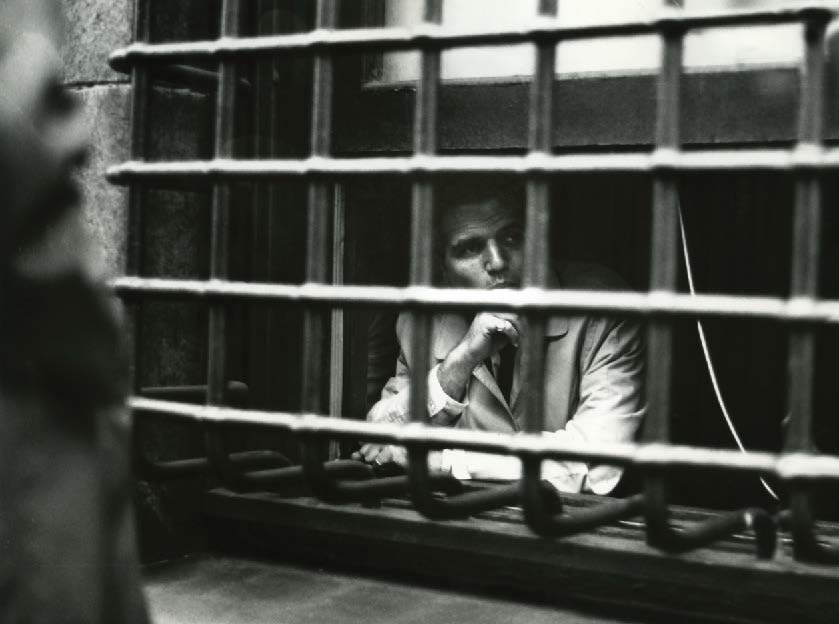

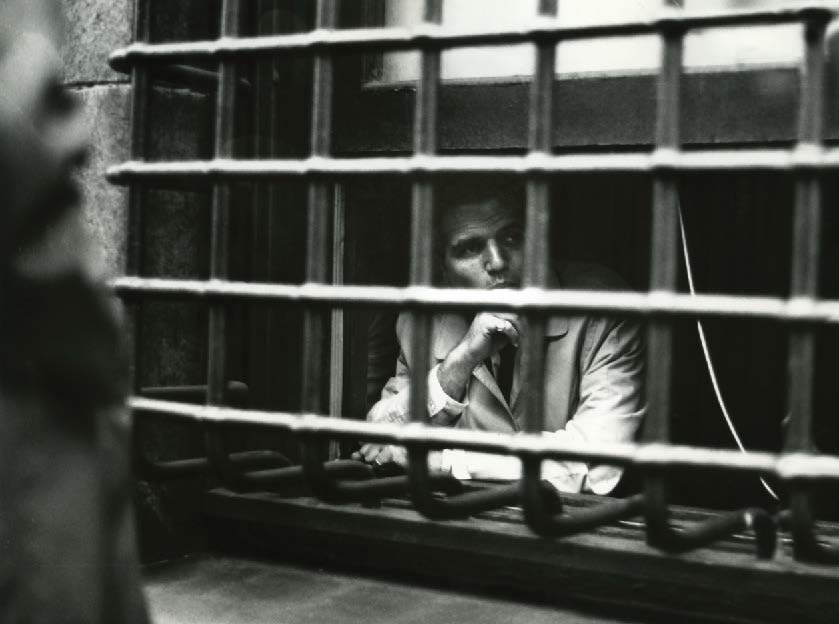

Henry S. “Harry” Coleman ’46, acting dean of the College, peers from his window in Hamilton. “Most of the students had a great affection for him,” Raymond M. Brown ’69 says. “So we would make sure he had food and everything he needed.”

The basic narrative of the campus blow-up has been well-chronicled: An April 23 Sundial rally morphed into a march on the gym site and an eventual sit-in at Hamilton Hall; acting College Dean Henry S. “Harry” Coleman ’46 was barricaded in his office there for 26 hours, receiving food and encouragement through his barred window on College Walk. Students refused to leave unless their demands were met; the principal ones called for the University to sever ties with IDA, abandon the Morningside gym project and grant amnesty for the occupiers. Officials were prepared to meet with protesters, but not to yield under such coercion.

On that first night, the black students in Hamilton asked the SDS group to take over another building; SDS reluctantly complied and at sunrise forced their way into Low Library. The stage was set for a much broader confrontation. And by concentrating in one building, the black students had multiplied their influence. Rumors that they were armed added to the authorities’ concerns.

During the next three days, while the administration hesitated and the faculty mediated, protesters occupied Fayerweather, Avery and Mathematics. It was a startling wave of defiance — “mysteriously dynamic,” Paul Berman ’71 writes in the foreword to the Cronin anthology. “The professors who watched in astonishment failed to see it sometimes, and so, too, did the journalists. But we students saw it. We felt it in the flesh. We trembled.”

Many students adamantly opposed the takeovers and threatened to take matters into their own hands. Coleman helped cool tempers at key moments, as did basketball coach Jack Rohan ’53, fresh off his team’s thrilling Ivy championship. Many more — whether sympathetic to the protesters’ aims but not their means, or merely curious or confused, or just wishing to continue their academic work — remained on the sidelines.

Beyond the gym and Vietnam protests in a year of worldwide upheaval, there were more parochial reasons why Columbia students rebelled that spring. Crisis at Columbia, the report of a fact-finding commission chaired by future Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox, cited problems of university governance, poor faculty morale, “appallingly restricted” student residential facilities and a general lack of community on campus: “The hurricane of social unrest,” they wrote, “struck Columbia at a time when the University was deficient in the cement that binds an institution into a coherent unit.” To that point, Robert Siegel ’68 counters: “Before blaming too much on the pathology of the Columbia experience, I would say that Columbia students were in fact acting on, and reacting to, the world around them — not being insulated from it by the comfort of their undergraduate experience. They were saying things are wrong in this university because it’s part of this country and this society.”

“We women do continue to march,” says Josie Duke Brown BC’69 (far left), leading a community action on Amsterdam Avenue.

Spirits were certainly high within the “liberated” buildings — one couple was married in Fayerweather by the campus chaplain — despite the gathering presence of hundreds of helmeted police officers beyond the Gates. And there were more subtle tensions, including a degree of gender inequality that would be more forcefully opposed in years to come. “Life inside Columbia’s occupied buildings was intense, intoxicating, and profoundly pre-feminist,” Nancy Biberman BC’69 recalls in A Time to Stir. Adds Carolyn Rusti Eisenberg GSAS’71: “To say that the atmosphere was macho is akin to saying it’s warm on the Equator. A group of 20-year-old white men, many of them close friends, paralyzing an entire university in New York — the media capital of the world — was an electrifying experience.” SDS’ firebrand press secretary, Josie Duke Brown BC’69, does not remember women being relegated to housekeeping chores, as some were, but she does agree that SDS did not look to them for leadership. “I certainly don’t feel that they were trying to cultivate the role of women,” she says.

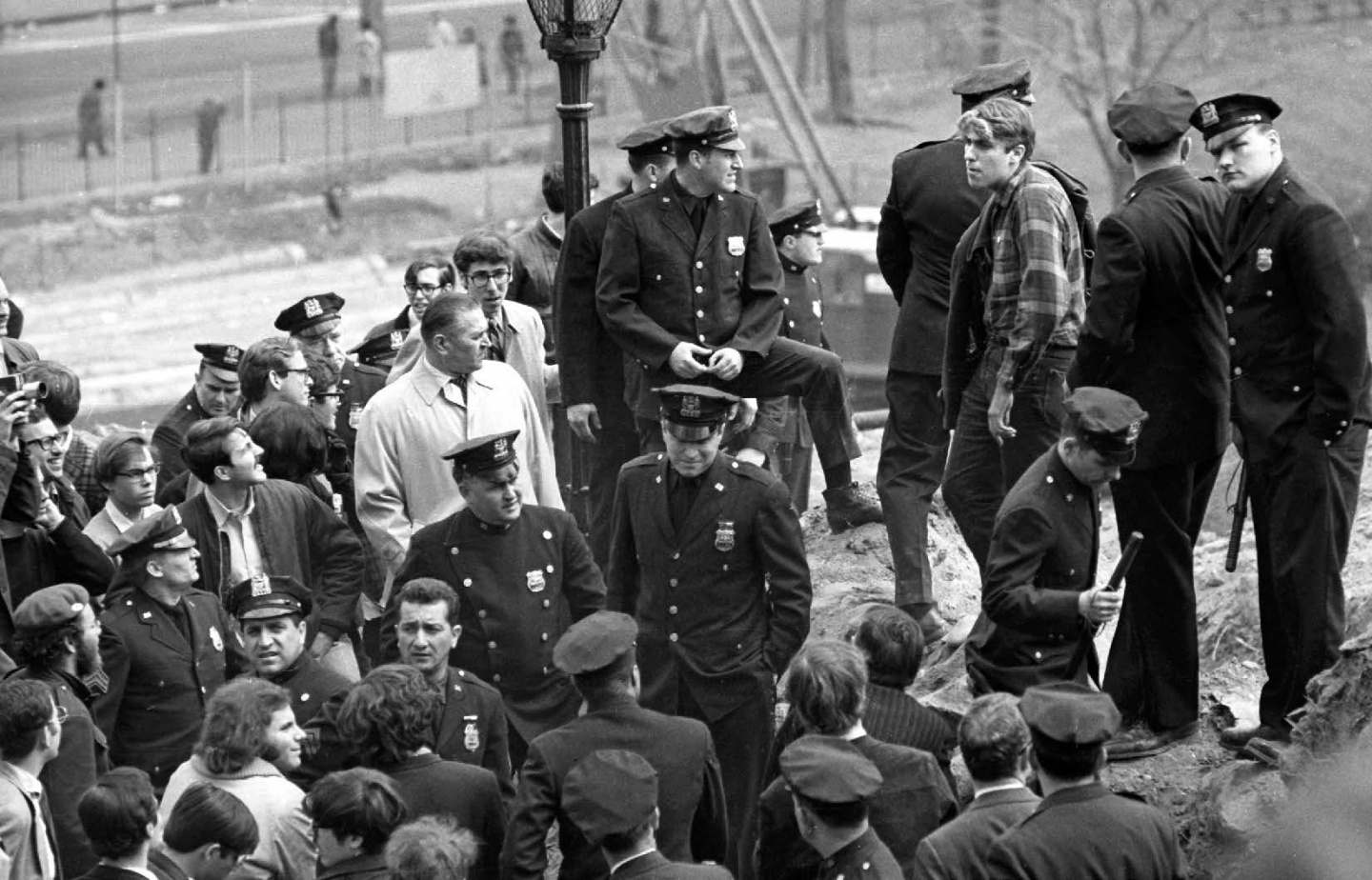

After several tense days of waiting and enduring obscene taunts from students, members of the NYPD’s Tactical Patrol Force had had enough by the time they were summoned to action in the wee hours of April 30. “When the order ‘hats and bats’ (helmets and nightsticks) finally came, there was no doubt in any cop’s mind about what was about to happen,” former officer Mike Reynolds says in A Time to Stir.

What followed has been described as a police riot, with plenty of heads cracked by those “bats”: 712 were arrested — including some 200 women — and there were 148 injuries. For a bastion of high-minded learning and civility, it was calamitous on every level.

In his 2009 memoir,

Underground: My Life with SDS and the Weathermen, Rudd remembers calling home from President Grayson Kirk’s desk in Low Library soon after SDS broke in on April 24. He reached his father in suburban Maplewood, N.J., still drowsy from sleep.

“We took a building,” Rudd told him.

“Well, give it back,” his father said.

While students in Low were helping themselves to Kirk’s sherry and holding endless strategy sessions, the 90 or so black students in Hamilton Hall held regular drills for assembling peacefully, getting arrested, handling tear gas. “We kept the place clean enough so you could eat from the floor,” Raymond Brown says. “That’s part of the ethos with which we were raised both individually and in the context of the movement — we’ve got to be better.”

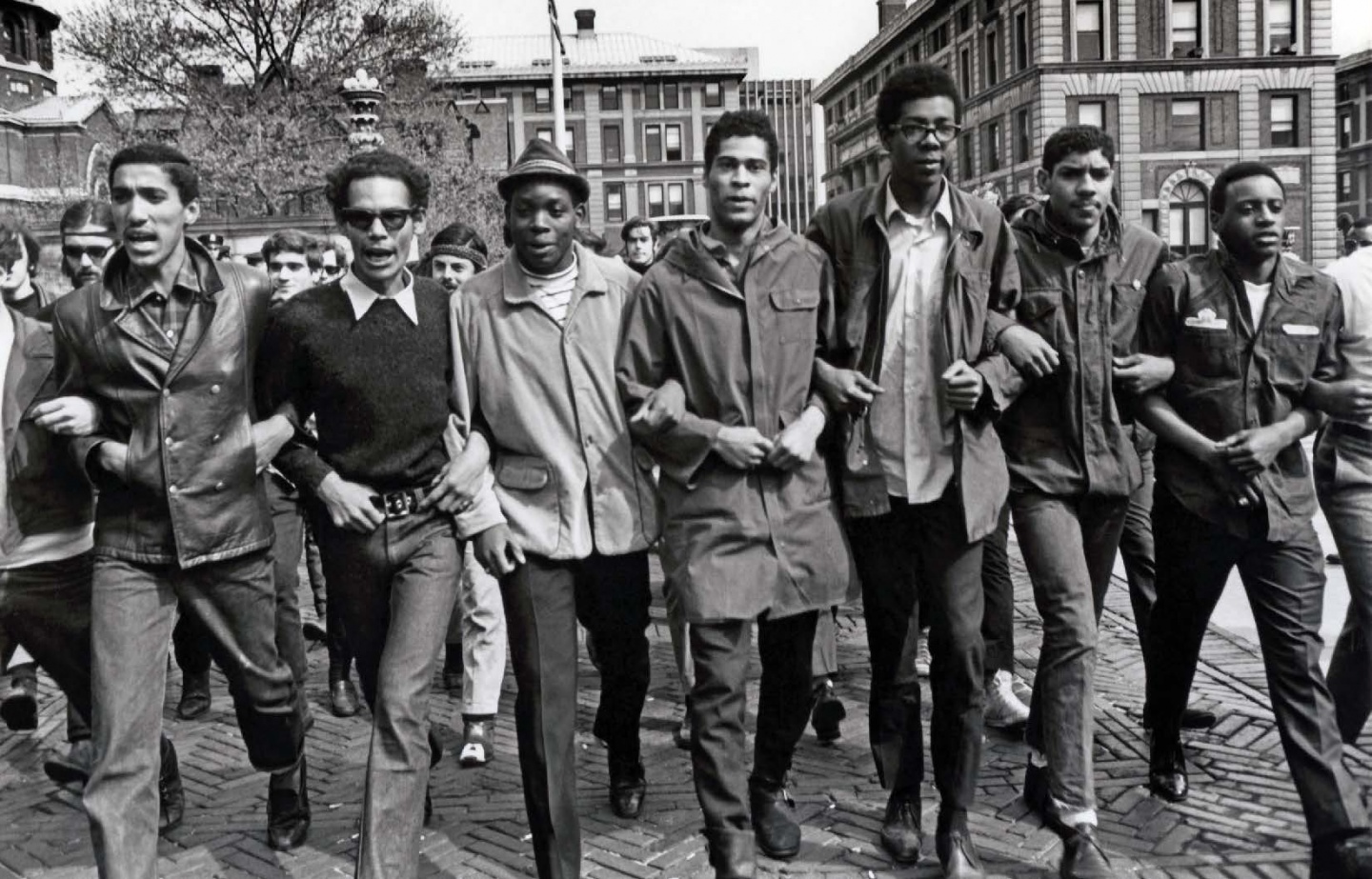

On the night of the bust, NYC Human Rights Commissioner William Booth helped the black students negotiate an orderly exit through an underground tunnel, away from cameras and onlookers, to be arrested by a black-led police team, with lawyers present. “They marched out with dignity as a well-disciplined army would,” historian Walter Metzger GSAS’46 later observed. “They were proving something very important to themselves.”

Important in part, Brown underlines, because the black students felt a dual responsibility: political solidarity, yes, but also an awareness that they represented a vanguard of hope and accomplishment. “The students were under tremendous pressure from parents and others who had sacrificed tremendously to get them there — who weren’t necessarily unsympathetic to the cause, but were not terribly sympathetic to their kids possibly getting expelled from school, either,” Brown says. “Getting your degree was in and of itself a political statement.”

The Bust triggered a massive student strike that effectively ended regular business at the University for the rest of the semester. Professors were given the option of grading all students on a pass-fail basis. Some held classes in their apartments, some on campus lawns or at neighborhood restaurants. The College canceled its traditional Class Day ceremony, and the University moved its June 4 Commencement exercises to the nearby Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine for security reasons. “Here at Columbia,” historian Richard Hofstadter GSAS’42 told graduates that day, “we have suffered a disaster whose precise dimensions are impossible to state, because the story is not yet finished, and the measure of our loss still depends on what we do. For every crisis, for every disaster, there has to be some constructive response.”

That night Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated in Los Angeles after winning the California primary. The year 1968 was far from over.