Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

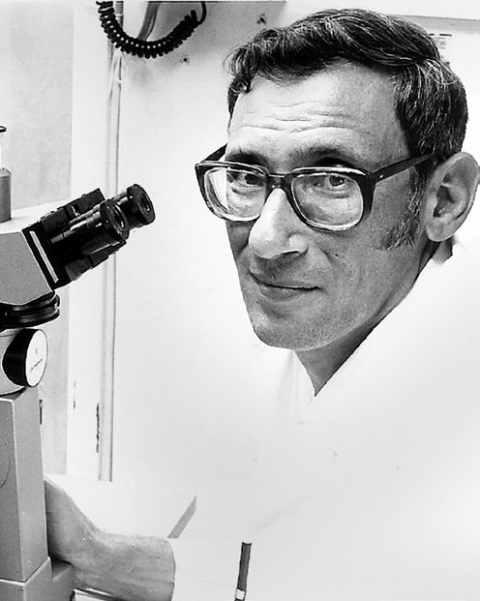

Public Health Pioneer Julius Schachter ’57

Schachter, who closed his laboratory at UC San Francisco last summer, says he came upon the focus of his lifelong work largely by circumstance.

“I hadn’t planned to do research on STDs,” he said in a Class Note sent to CCT last year, “but serendipity always plays a role, and living in San Francisco through the Summer(s) of Love provided plenty of opportunity. Chlamydial infections were relatively new, and this gave us chances to make real contributions to public health.” Schachter, who lived in Corte Madera, Calif., with a second home in Nussloch, Germany, died on December 20, 2020, due to Covid-19.

Schachter was born on June 1, 1936, in the Bronx and was the first in his family to attend college. A chemistry major, he earned a master’s in physiology from Hunter College in 1960 and a Ph.D. in bacteriology from UC Berkeley in 1965. His first academic job was as an assistant research microbiologist at UC San Francisco, and he stayed there for 55 years.

Studies in Schachter’s laboratory focused on the epidemiology and clinical manifestations of chlamydial infections. Schachter recognized that chlamydia was not just an ocular or sexually transmitted disease, but also a systemic one that caused pneumonia in newborns. As a result, screening pregnant women for chlamydia and treating the infected women has become the standard of care in the United States and many other countries.

His laboratory also produced a proof of concept study showing the effectiveness of community-wide treatment of trachoma with azithromycin. This is now the linchpin of an effort sponsored by the World Health Organization at eliminating the disease.

After closing his research lab, Schachter kept his academic appointment and planned to continue analyzing data and writing up his last few studies. “Looking back, I recall the usual academic frustrations, getting funding and so on, but all in all, it has been a blast,” he said of his career.

Schachter was predeceased by his first wife, Joyce Poynter. He is survived by his second wife, Elisabeth Scheer; daughter, Sara ’91, and her husband, Brent Bessire ’91; sons, Marc and Alexander; brother, Norbert ’60; and three grandsons.

— Alex Sachare ’71

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu