Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

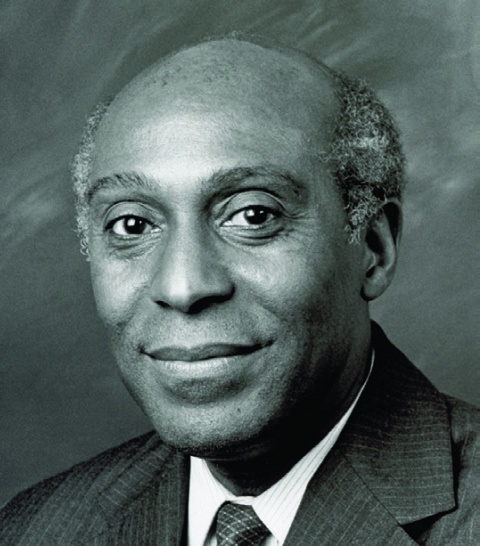

In Memoriam: Charles V. Hamilton, Political Scientist and Civil Rights Champion

CCT_Summer_2024_vWEBFINAL1_Page_04_Image_0001.jpg

COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

In 1967, Hamilton and Stokely Carmichael, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, published the seminal 1967 manifesto Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America.

“Their book convulsed moderate and more conciliatory Black groups like the NAACP nearly as much as it confounded the white liberals who had traditionally supported civil rights,” wrote The New York Times. “Its conclusion that racism was embedded in the nation’s institutions further antagonized white people who had opposed any preferences for Black people in government policies to mitigate discrimination in housing, jobs, public accommodations and education.”

Hamilton did not declare himself a militant or revolutionary, but his views often broke ranks with established groups such as the NAACP or the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which sought broad political and multiracial coalitions. He increasingly stressed that Black communities and other minorities take greater control of their own destinies. For Black people to belong to mainstream America, he said, they had “to understand that we are Black people and not ashamed of that.”

“Chuck was very definitely the intellectual alter ego to Stokely Carmichael,” his friend Jeh C. Johnson LAW’82, the former secretary of homeland security, said in an interview. “He was a quiet, dignified, soft-spoken, very progressive intellect behind the Black Power movement.”

“The point we are trying to make in this book is that one’s individual stance in relationship to the Black man is irrelevant,” Hamilton told Studs Terkel in a radio interview in 1967. “It’s what the system does, and that’s why we use the term ‘institutional racism.’”

Less than a decade later, as a strategist within the Democratic Party, Hamilton was criticized when he urged that the 1976 party platform be “deracialized” and promote benefits for disadvantaged people regardless of their color. He believed that the repercussions of institutional racism should be addressed without specifically mentioning race — to avoid a backlash from white voters — and that common ground needed to be found between poor Black and white citizens.

Hamilton was born in Muskogee, Okla., on Oct. 19, 1929, the middle of three children. His father, Owen, was a garage mechanic. His mother, Viola (née Haynes), brought Charles, his older brother and younger sister to Chicago’s South Side in 1935.

He aspired to be a journalist but realized the opportunities for him as a Black man were few. Civil service meant security, so Hamilton gravitated toward government. He would later be an organizer for Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley and a Democratic Party strategist in several election cycles, including Jimmy Carter’s successful presidential run in 1976.

After serving in the military in the late 1940s, Hamilton graduated from Roosevelt University in Chicago with a degree in political science in 1951. He enrolled in law school but did not stay there long, instead earning a master’s from Chicago in 1957.

“I never wanted to be just a professor,” he said in an interview with the Annual Review of Political Science in 2018. “I wanted to turn my academic life into an activist one.” In 1958, he joined the faculty of Tuskegee Institute, but his contract was terminated just two years later. “I was too radical,” he recalled in 2021. “I was teaching the kids how to contact Congress and march and protest.”

Martin Luther King Jr. planned a visit to Tuskegee in the late 1950s, but administrators were so fearful of campus unrest that King’s speech was delivered at a nearby church. Hamilton saw a hero in King and was the only Tuskegee professor to attend. He and King posed for a photo that Hamilton treasured all his life.

Hamilton returned to Chicago, where he earned a doctorate in 1964. He then taught at Rutgers University, Lincoln University and Roosevelt University before joining Columbia, where he became one of the first African Americans to hold an academic chair at an Ivy League university.

His wife, Dona Cooper Hamilton SW’82, died in 2015. He is survived by a stepdaughter, Valli. His daughter, Carol, died in 1996.

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu