An inside look at the complex balance that shapes academics at Columbia College.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

This website uses cookies as well as similar tools and technologies to understand visitors’ experiences. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University’s usage of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice.

An inside look at the complex balance that shapes academics at Columbia College.

Kathryn B. Yatrakis GSAS’81, Dean of Academic Affairs, Columbia College, and Senior Associate Vice President for Arts and Sciences, is retiring on June 30 after serving as academic dean at the College since 1989. Columbia College Today asked her to reflect on the academic changes she has seen in her 27 years in Hamilton Hall.

Tradition and Innovation is the title of a short report authored by Professors Robert Belknap SIPA’57, GSAS’59 and Richard Kuhns GSAS’55 in 1977 that captures a theme that has defined the College for many years — if not since its inception — including my 27 years as academic dean.

A few years before my arrival in Hamilton Hall, the College underwent two significant institutional transformations: first, it became fully residential, and second, it was the last of the Ivy League schools to admit women. By 1989, when I started my tenure as academic dean, the College was just beginning to reap the benefits of these fundamental changes. Since then, the physical changes of the campus are obvious and easily recognized: Ferris Booth Hall replaced by Alfred Lerner Hall; the new Northwest Corner Building for science; an inviting glass atrium entrance to the Admissions Office off College Walk; helpful signage and the grace of landscaping throughout.

Other important changes that took place as the years rolled by were not as easily observed. There was growth in administrative staff in admissions, student advising and alumni affairs in order to enhance the College’s support to students, faculty and alumni. At the time there was little formalized academic administrative structure. For example, in 1989 a part-time student in a fourth-floor office in Hamilton Hall was the Core Curriculum’s sole administrator; now its administrative support is based in the Witten Center for the Core Curriculum on the second floor, which includes offices, a conference room and library, and a staff that supports the faculty chairs of the various courses, facilitates preceptor training, plans and schedules courses according to student need, organizes a range of co-curricular programs and much more. Throughout these years there were also academic changes in concert with enduring values that can be seen in the reshaping of the curriculum, the makeup of the faculty and the profile of the College’s students. I will start with the curriculum.

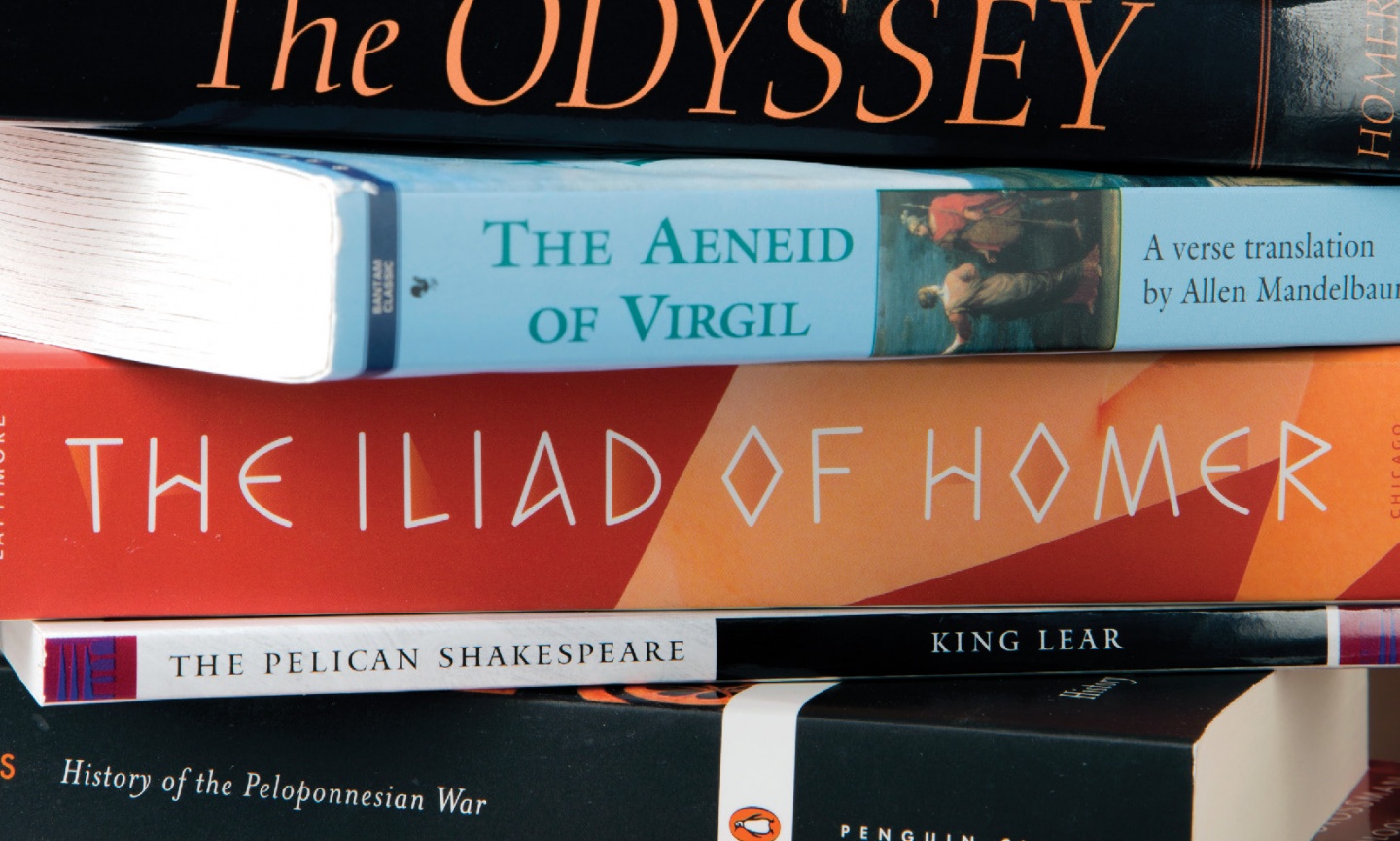

The mark of a strong and vibrant curriculum is an intellectual stability that is yoked to intellectual change. This is the inevitable result of groundbreaking research and the discovery of worlds of knowledge. It should come as no surprise to CCT readers that the best example of this intellectual stability is found in the Core Curriculum. The basic structure of the Core has remained the same through the years. The four central courses — Contemporary Civilization, Literature Humanities, Music Humanities and Art Humanities — are still taught as small seminars in which informed discussion is central. They are defined by careful reading of texts, listening to music and seeing art. The Core has been stable through these many years but this stability is marked by constant change, and not only changes in syllabi but changes in every class in which a student interrogates texts and teachers with a new voice. The vast majority of alumni likely will remember the common intellectual journey offered in CC, Lit Hum, Music Hum and Art Hum; now jazz has been added to Music Hum, museum tours are a regular feature of Art Hum and several texts have disappeared, reappeared and disappeared again on the CC and Lit Hum syllabi.

Jörg Meyer

Core syllabi are reviewed every two years. I well remember an intense discussion among the CC staff considering whether the revised syllabus should include Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman or John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty and the Subjection of Women. Passions ran high and the debate raged as the Wollstonecraft supporters insisted that there should be a woman writing about women while those advocating Mills insisted that he was a much better writer and even though not a woman, made the clearer, cogent and more thoughtful argument on behalf of women. Though I did not remain to the bitter end of the debate, I believe that the Mills’ supporters prevailed but the outcome was less important than the fact that a strong and informed argument was made on both sides. And that, for me, is the essence of our Core Curriculum.

In addition to CC, Lit Hum, Music Hum and Art Hum, all College students are still required to reach an intermediate-level proficiency of a language other than English, must take a first-year writing course and must complete two semesters of physical education. From time to time, the faculty review and discuss all Core requirements so that this traditional curriculum — this constant and stable curriculum — is also innovative.

For example, in 1988, the faculty was asked to consider the recommendations contained in a report issued by a faculty committee charged with evaluating the two-semester science requirement. The Columbia College Committee to Review the Science Requirement, chaired by George Flynn GS’64, GSAS’66, a chemistry professor devoted to teaching undergraduates, recommended that the science requirement, which in the 1970s had been reduced from four to two semesters, be returned to four semesters. However, there were not enough courses offered for non-science students and not enough faculty to teach courses necessary for the full four-semester requirement, so it was increased only from two to three courses.

A decade later, not satisfied that there was any coherence to the science requirement, some science faculty, led by David Helfand, a legendary professor of astronomy, started to discuss the need to develop a science Core course that would be taken by all College students. While this was considered to be a radical idea, it was something that College faculty actually had discussed in 1933, and a pilot course was offered for a few years. The issues then were the same issues that defined the discussions more than 60 years later: What would be the substance and structure of a Core science course? Would it be a course required of all students, science students and non-scientists alike? Unlike faculty of the past, however, today’s faculty were not deterred, and in 2004 a new course, “Frontiers of Science,” was added to the Core on an experimental basis.

Frontiers of Science, a bold curricular experiment, is meant to introduce science to all students — from methodology to important theories and groundbreaking research — so as to excite students about this human endeavor that is central to our lives both collectively and personally. Just like our earlier Core courses, however, this course is undergoing review by another faculty committee that will recommend whether the current format is to be continued or if another format would be a pedagogical improvement. That science will have a place in the Core, however, has already been decided.

In December 1988, another faculty committee, this time chaired by Wm. Theodore de Bary ’41, GSAS’53, the John Mitchell Mason Professor Emeritus, provost emeritus, special service professor and indomitable College and Core enthusiast, was asked to chair a faculty committee to review the Core and especially recommend the replacement for what was called the Remoteness Requirement, remembered only by older alumni (and me): a two-semester requirement meant to broaden a student’s academic work and thus prevent students from “overspecializing” by requiring that every student take at least two courses “remote” from the student’s major. The faculty decided to replace the remoteness requirement with the two-semester “extended Core,” which later became the Major Cultures requirement and is now known as the Global Core requirement, which insists that students “engage directly with the variety of civilizations and the diversity of traditions that, along with the West, have formed the world and continue to interact in it today.” The faculty of the Committee on the Global Core continues to review and refine this requirement, but there is no question that it will remain a Core requirement for many years to come — or until the faculty decide otherwise.

Museum visits, such as this one to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, are now an integral part of Art Humanities.

Even the swim requirement has not been exempt from faculty scrutiny. More than 20 years ago there was a proposal made by a number of faculty that students should have the choice of either passing the swim requirement or passing a CPR course. The argument was rather simple: knowing CPR might be even more valuable than knowing how to swim. The Physical Education Department was not opposed to the proposal and all was in place for a faculty vote; the discussion went on for a while until one senior faculty member rose and asked a simple question: “If it ain’t broke, why fix it?” The proposal was voted down and never raised again, and so the swim requirement remains. Occasionally I hear from students and alumni alike that they are so happy that now they know how to swim.

A review of the majors and programs available to students from 1989 to 2016 reflects a curriculum that is centered in traditional disciplines but also responsive to new ways of knowing and thinking. The 1988–89 Columbia College Bulletin lists 54 academic departments and programs of study, and while the 2015–16 Bulletin lists 56, the substantive changes are noteworthy. No longer are there programs in Geography and Geological Sciences; instead we have the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology as well as a program in Sustainable Development. There is no longer an Oriental Studies entry, but we do have a Department of East Asian Languages and Cultures and a Department of Middle East, South Asian, and African Studies. There is no longer a Speech program — though perhaps there should be.

Faculty love teaching College students because they can be counted upon to ask provocative questions that can spark thinking by both parties.

What is not always obvious is that these changes in labels reflect a process of intense faculty engagement working at the vanguard of their disciplines while locating their work within the traditions of a liberal arts curriculum. A good example is that of the change from Painting and Sculpture to Visual Arts, which came about as a result of the work of the faculty committee on undergraduate arts that was appointed in 1989 and chaired by David Rosand ’59, GSAS’65, the Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History and a gifted teacher of Renaissance art andArt Humanities. Rosand, who died in 2014, was not sanguine about the faculty agreeing to create a major in visual arts. As he told Spectator, the College’s Committee on Instruction will present the biggest challenge to the committee’s proposals because of the members’ adherence to a traditional curriculum: “… the most challenging issue — how to introduce studio work into a [liberal arts] curriculum.” While his skepticism was not unwarranted, Rosand was delighted when the faculty on the Committee on Instruction — after many interviews with colleagues in the arts and related departments, careful deliberations and substantive discussions among themselves — agreed that what was a program in painting and sculpture would be now be shaped into a major in Visual Arts that would include courses in printmaking, lithography and drawing.

Even within established programs and majors, the curriculum is reviewed and reshaped as necessary. Urban Studies, the program with which I have been involved both as a faculty member and academic administrator since the mid-1970s, is a multidisciplinary program that has been offered to students as a major since the early ’70s. The major has a required junior-level seminar that I had taught for years as “Contemporary Urban Problems”. We focused mostly on New York City with perhaps a nod to Chicago — think the famous Steinberg illustration — and we always examined “problems,” which abounded in cities throughout the ’70s, ’80s and early ’90s. Slowly the urban condition changed and we started analyzing other cities and in the early 2000s the name of the course was changed to “Contemporary Urban Issues.” Today we are as likely to examine housing in Paris, the waterscape of Amsterdam or the exploding population of Lagos.

Faculty meet regularly in the Core Conference Room in the Witten Center for the Core Curriculum to discuss common issues.

And so, in my time here, we have seen extraordinary developments in the undergraduate curricular offerings that reflect a changing academic terrain. Obvious changes include new programs in American Studies, Business Management, Comparative Literature and Society, Ethnicity and Race Studies, Human Rights, Jazz Studies, Jewish Studies, Latin American and Caribbean Studies, and Women’s and Gender Studies, and new courses such as “Architecture of the 11th and 12th Centuries in the Digital Age,” “Science for Sustainable Development,” “American Consumer Culture,” “Race and Sexuality” and “Economics of Uncertainty and Information,” to name just a few. There are also new opportunities for undergraduates to take classes in the graduate schools of Business, Journalism, Law and Public Health. No less important is the constant review of the curriculum by the faculty, who strive to ensure that the intellectual work the College’s students perform addresses the questions of our day, seeks solutions for tomorrow and shapes more informed questions for the future while never losing sight of our disciplinary foundations.

The faculty who teach College undergraduates are still some of the best and brightest minds in the nation, as they were in years past. When asked by a consultant many years ago what I thought the faculty thought about College students, I responded that they loved teaching them. He said that this had been confirmed by their surveys and added that this was not the case in one of our peer institutions that his firm recently had analyzed. Good teachers are good students; faculty love teaching College students because they can be counted upon to ask provocative questions that can spark thinking by both parties.While faculty continue to expand the boundaries of knowledge with their research, they also enjoy teaching undergraduates who will shape our future. In this vital respect, the faculty is the same as it was 27 years ago — exceptional scholars and teachers. But in some important ways, the faculty also has also changed.

In 1989 there were approximately 400 Arts and Sciences faculty; 18 percent were women, and an imperceptible number were faculty of color. Today, with an Arts and Sciences faculty of about 550, 35 percent are women and 8 percent are underrepresented minorities. New voices and new intellectual perspectives come with new faculty, again keeping our educational mission alive and alert to new landscapes of thought. But there is still much work to do and our faculty are working hard to improve the pipeline via our NSF-funded Bridge to Ph.D. Program in the Natural Sciences, overseen by Professor Marcel Agüeros ’96; our Andrew Mellon Foundation-funded Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship program, led by Professor Carl Hart; and our Kluge Scholars Program as well as diligent searches for underrepresented faculty.

Of course, as the faculty have changed during the past 27 years, so too have our students.

Leslie Jean-Bart ’76, JRN’77

In my early days, it was not unusual to meet students who were unaware that they were coming to a college in the middle of a major city or that they would be expected to complete the Core. In the early ’90s publications meant to attract applicants to the College (no website and virtual campus tours then!), students were pictured sitting on the campus lawns, trees in full bloom and shrubs marking an idyllic, rather rustic scene. It did not look as if Columbia were located in the center of a bustling city. A consultant strongly suggested that either we embrace the fact that we are in New York City or move the campus to Westchester. Also in those days, I well remember one student recalling that she assumed that she was admitted to the College because of her excellent high school experience in theater and that would be her major. It was not until she arrived on campus that she realized not only that Columbia did not have an undergraduate theater program but it did have a required Core Curriculum. She described herself as a very “unhappy camper” sitting in Literature Humanities. But miraculously (according to her), she found herself growing to love literature as she had never experienced it in this way before. This was the start to her eventual undergraduate study of medieval literature, and she went on to a Ph.D. program after graduation.

Today, the vast majority of students use the Internet to thoroughly research all of the colleges they are seriously considering attending. They take virtual as well as on-campus tours where they bombard tour leaders and admissions staff with questions and in many cases, families are also involved in the admissions process. Our admissions numbers look very different from when I arrived at Columbia. In the early ’90s, our admissions pool hovered around 7,000 and our entering class was around 900. I remember thinking that it would be excellent if we could double the number of applicants. Today, with almost 30,000 applicants, we have more than surpassed that goal and we admit a class of about 1,100 with an admit rate around 6 percent. We are attracting some of the best and brightest students in the world but also rejecting many talented students.

It has long been said that the mark of a College student is that when the response to a question asked is “no,” the student assumes that you have misunderstood the question. I might interject here that I finally realized that this was a key to my understanding of my own husband, Peter Yatrakis ’62. I think that this attitude has not changed through the years. Students today expect more services and support than students of the past but this probably can be said of every succeeding student generation.

Ed Rickert ’36, at one of his reunions in the early 1990s, told me about an experience of his that gave an account of the relationship of College students to the president of the University, at least in those days. Rickert, who hailed from Indiana, explained that the one suit he owned had burn holes in it after he participated in a demonstration in front of President’s House. He told me students were complaining about an increase in tuition — I don’t remember the amount, but it was probably something like $10 — and students marched in front of the house one night with torches for light. Some sparks escaped and burned a few holes in Rickert’s suit. “You mean that students wore suits to a protest demonstration?” I asked. “Oh, yes,” he responded. “We would never think of marching in front of President [Nicholas Murray] Butler [Class of 1882]’s home not wearing a suit!”

Students today have very different attitudes toward presidents and deans — and vice versa. President Lee C. Bollinger’s activities with students — his fireside chats, annual Fun Run, countless student group meetings and individual conversations with students — present a world unfamiliar to Butler and presidents of the past. When George Ames ’37, a generous benefactor of the College both by his leadership and treasure, was chair of the Board of Visitors, he recalled that there was no truth to the story that Butler never spoke to an undergraduate. Ames went on to explain that after a particularly heavy snowstorm there was a narrow path shoveled through the snow, barely wide enough for one person to get by. Ames the undergraduate was walking one way when, to his horror, he saw Butler walking down the same path in the opposite direction. “Step aside son,” Butler said gruffly to Ames. Years later, Ames told this story with a sparkle in his eye to remind us that we should be careful not to believe everything we hear. You see, he would say, he was proof that Butler did indeed speak to undergraduates.

If today’s students expect more of administrators, faculty and deans, they also expect more of themselves — and at times that can be challenging. An April 14 article in Spectator headlined, “Are Columbia Students the Most Stressed in the Ivy League?”, argued in the affirmative and cited as a reason for this stress students’ heavy academic workload. I was rather perplexed by this argument, in part because graduation requirements have not significantly changed in the past 30 years. So why do today’s students complain of academic stress? In the 27 years I have been the academic dean it has become more likely that students pursue more than one major or concentration, which adds to their workload. Our research has also shown that students think their classmates are taking five or six classes a semester, so they should as well. But we also know that these trends are not unique to Columbia, and this generation of students is particularly anxious about post-college prospects.

Faculty have long been concerned that students must take an average of five courses per semester to reach the 124 credits needed to graduate, as opposed to the four courses required at a number of peer institutions. As a result, the Educational Policy and Planning Committee has worked diligently the past few years to increase the number of credits for those lecture courses with mandatory discussion sections in an effort to help reduce the number of courses that students must take each semester. The College’s Committee on Instruction also recently voted to reduce the maximum number of credits a student can take per semester before approval must be received. Both these changes are meant to allow students to delve a bit more deeply into their course work and reduce their academic stress.

Class Day and Commencement for the Class of 2016 concluded in mid-May and as I participated in these ceremonies, I thought again about how much the College has changed through the years and yet how much has endured; how much the evolution of academics at the College is a combination of tradition and innovation, and a balance of stability and change.

One constant throughout Columbia College’s history is its strong commitment to the teaching of the liberal arts. In 1754, prospective students learned about a new college, King’s College, from a newspaper advertisement that announced the establishment of this school for students who wished to study the “learned languages, the liberal arts, and the sciences.” This was a College that was created with the “good design of promoting liberal education,” that is, an education not to prepare students for the practice of any particular vocation but an education that would teach students to “reason exactly, write correctly and speak eloquently.” King’s College would offer an education “instructing students in the arts of numbering and measuring; the ancient languages, mathematics, commerce, history, and government” — strongly resonant with the academic mission of Columbia College today.

I think it is quite remarkable that the basic academic commitment of the College to the teaching of the liberal arts has remained steadfast, and was enhanced in 1919 when Contemporary Civilization, the first Core class, was required of all College students. What I think is also quite extraordinary is that while the academic center of Columbia College has remained constant, so much else has changed, even in my tenure as academic dean.

If today’s students expect more of administrators, faculty and deans, they also expect more of themselves — and at times that can be challenging.

The curriculum is still anchored by the Core, but the Core itself has responded to new areas of study and ways of thinking. Some departments and academic programs have come and gone, and there are new courses that interrogate our world today, yet the College curriculum would be familiar to even the most senior of our alumni. Faculty continue to be some of the best and brightest scholars in the world and as in past years, they are challenged by teaching College students who can be counted upon to question basic disciplinary assumptions and theoretical conclusions. And our students? Perhaps a bit more competitive, focused and interested in a more global education but they remain extremely well trained in critical thinking.

Participating in this year’s Class Day, I was reminded that my first Class Day, in 1990, was held in the gym, and family members had to make their way, sometimes slowly and unsteadily, up the bleacher stairs to their seats. We may not have had to worry about inclement weather but it was clear that the gym was not the best venue for this celebration. Soon after, because of the growing number of students, Class Day exercises were moved to South Lawn, and that was a much better site, as long as it didn’t rain. In those days, few faculty attended Class Day and there were no receptions to celebrate students’ accomplishments with their families and guests. How different it is today with tents, jumbo screens, faculty in attendance, the Alumni Parade of Classes, presenting graduates with their class pins, and numerous receptions.

Yet in some ways, Class Day this year was not so different from 27 years ago; today, as then, each graduate who crosses the stage has been the beneficiary of a rich and enduring academic tradition that has held fast to its center in the Core Curriculum and devotion to the liberal arts while at the same time reflecting innovations in fields of knowledge and ways of knowing. I know that as our graduates become wiser — life has a habit of making them so — they will appreciate even more the importance of this tension between tradition and innovation that has marked academics at Columbia through the years.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu