Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

A Dance Pioneer Finally Gets His Due

Ted Shawn, often called the “Father of American Dance,” was so sure about his place in cultural history that before his death in 1972, he drafted a letter to future biographers listing what topics should be written about him and the order in which they should be written. But none of those books ever came. Until now.

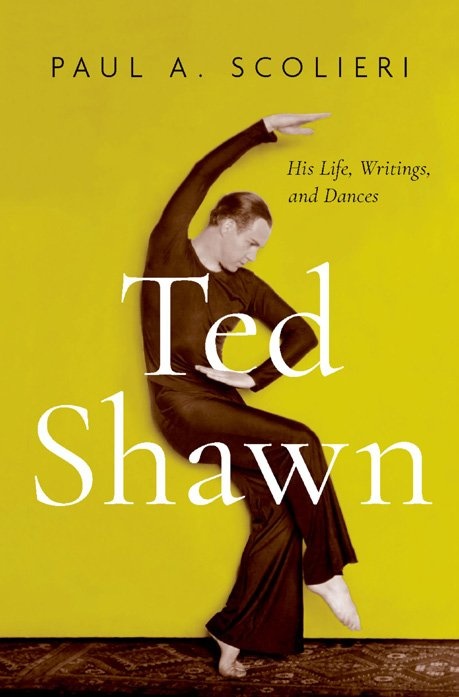

In Ted Shawn: His Life, Writings, and Dances (Oxford University Press, $39.95), Paul A. Scolieri ’95, chair and professor of dance at Barnard, offers the first scholarly account of Shawn’s pioneering role in American modern dance and reveals the untold story of Shawn’s homosexuality, his choreographic vision and his impact on society.

Between 1915 and 1940, Shawn transformed dance from popular entertainment into a theatrical art, and in the process, made dancing an acceptable profession for men. With his wife and dance partner, Ruth St. Denis, he founded Denishawn, the first modern dance company and school in the United States. (Martha Graham was a protégée, and went on to become a legendary dancer and choreographer in her own right.) Shawn directed the first all-male dance company, Ted Shawn and His Men Dancers, and was also the founder of Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, the internationally known performance venue and school in Becket, Mass.

Scolieri spent 10 years researching Shawn for this biography. “His is one of the best-documented lives of the 20th century,” Scolieri says. “He maintained records from childhood — he had a strong sense that his life would be extraordinary.”

The importance and influence of Ted Shawn was imprinted on Scolieri’s life early. The Long Island native discovered a passion for dance in childhood, and studied performing arts at his Catholic high school while also training as a student at the Martha Graham School in Manhattan. “I would go to school and then take the train into the city,” Scolieri says.

When it was time for college, he wanted to carry on his training but not at a conservatory; at Columbia, he was among the first students (and the first man) to major in dance. His training at Martha Graham continued alongside his studies in the Core Curriculum: “I was dancing Graham pieces inspired by Greek myth at the same time I was also in Lit Hum, and learning Graham’s choreography for The Rite of Spring while studying Stravinsky’s score in Music Hum,” he recalls. “It all felt fully integrated.”

A Global Core course in pre-Colombian art set Scolieri on the path to writing his first book, Dancing the New World: Aztecs, Spaniards, and the Choreography of Conquest (2013). “I got so excited by the art, the story of conquest and the imagery that it became my doctoral dissertation,” he says. It also brought him back to the Columbia community: In 2000, Scolieri was hired to teach a class in Latin American and Caribbean dance at Barnard. He taught for a few years as an adjunct before becoming a full-time professor in 2003.

Scolieri says that though everyone in the dance world knows of Shawn, a lot of the details weren’t clear. “People wondered, ‘He was married to a woman, but was he gay?’ He was one of those guys who kept the lock on the closet. And in order for him to have prestige and stature and visibility, he engaged in a lot of internalized and externalized homophobia.” After the Stonewall uprising in 1969, Shawn was ready to tell a more authentic story of his life, and was in the interview process with one of his former students when he had a heart attack. Scolieri was able to use the seven days of recorded conversations in his writing.

“I tried to tell his story in a way that he would have told it had he been able to be honest, and with the vantage of 50 years to understand where he fit into the larger puzzle of American cultural life,” Scolieri says. “Shawn was born into a world with no concept of homosexuality, modernism or dance for men. His life was about braiding these emerging ideas together. Through my research I was able to better understand the social vision he had and the sacrifices he made.”

Scolieri gets reflective when he considers the realities of Shawn’s life versus the life he shares with his husband, Lavinel Savu ’94, and their three daughters. “There’s not a moment that I don’t think that my life and my career are everything that Shawn desired,” he says. “The part of the world I get to enjoy is in large measure owed to what Ted Shawn bodied forth.”

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu