Master essayist Phillip Lopate ’64 cast a wide editorial net to tell America’s stories

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Master essayist Phillip Lopate ’64 cast a wide editorial net to tell America’s stories

LAURE-ANNE BOSSELAAR

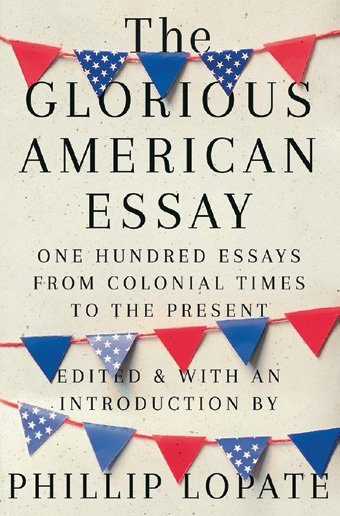

Now he’s back with another ambitious collection, The Glorious American Essay: One Hundred Essays from Colonial Times to the Present (Pantheon, $40), a spectacular showcase for his favorite form of prose.

A survey of Lopate’s relationship with essays dates to 1977. He was writing fiction and poetry when a book by the Romantic William Hazlitt caught his eye from the shelf of a summer house. What he found in its pages genuinely thrilled him: “I fell in love with the essay form,” he says. At that time, essays were seen as uncommercial (Lopate points out that, historically, their value has waxed and waned), but as he started to write them himself he experienced a new sense of control and power. “I could take that ‘Phillip Lopate’ character and make him do anything.”

Lopate reflected on this creative discovery in his moving 2010 essay, “The Poetry Years”: “I found in the personal essay a wonderful plasticity, which combined the storytelling aspects of fiction with the lyrical, associative qualities of poetry.” As he found his authorial voice, he began to publish a series of appealingly original collections, among them the acclaimed Bachelorhood: Tales of the Metropolis (1981) and Against Joie de Vivre: Personal Essays (1989). Lopate’s wry and subtle vignettes from city life alternate urbane intellectualism with an earthy, gloves-off Brooklyn honesty.

In addition to publishing books in all genres and teaching everywhere from Hofstra to the University of Houston (he is currently a professor of nonfiction writing at Columbia’s School of the Arts), Lopate edited well-received anthologies. In 2015, after compiling two Library of America collections on New York and movie criticism, he got the idea to do “a big book” featuring essays on the history and character of America.

He envisioned The Glorious American Essay as a “big tent” book, perhaps to mirror the inclusive character of the nation it was meant to define. Lopate cast a wide editorial net, including speeches (George Washington, Martin Luther King Jr. and others), letters (Frederick Douglass), sermons (Jonathan Edwards) and papers (Jane Addams), as well as more conventional essays (Elizabeth Hardwick and Vivian Gornick). He also ventured beyond the realm of literature. “Every discipline has exceptionally gifted writers,” Lopate proclaims in the introduction, excerpted here, explaining his inclusion of texts by scientist Lewis Thomas, theologian Paul Tillich and philosopher John Dewey. “I wanted to shake up the idea of what an essay was,” he says.

What unifies Lopate’s diverse selections is his unwavering focus on his theme. As the 100 essays travel forward in time, from Puritan preacher Cotton Mather to British novelist Zadie Smith, they provide glimpses of a nation in transition, always struggling to achieve or redefine the ideal society envisioned by its founders. In “The Twilight of Self-Reliance,” writer Wallace Stegner calls this ongoing labor “the greatest opportunity since the Creation — the chance to remake men and their society into something cleansed of past mistakes;” novelist Jamaica Kincaid, in “In History,” calls the New World a land with “the blankness of paradise.” Eloquent texts from different American eras “converse” with each other, Lopate points out, sounding and resounding the same themes with different emphases, rhyming without repeating as history is said to do.

His mosaic portrait of the nation was published the same month as the tumultuous 2020 presidential election, which Lopate thinks makes the essays “stunningly relevant.” “One thing [the book] clarifies is the notion of the American experiment, with its ideals of democracy, equality and a more perfect union,” he says. “The fact that these ideals have not yet been fully achieved, have even been betrayed at times, means we all have much work to do.”

— Rose Kernochan BC’82

The essay is a literary form dating back to ancient times, with a long and glorious history. As the record par excellence of a mind tracking its thoughts, it can be considered the intellectual bellwether of any modern society. The great promise of essays is the freedom they offer to explore, digress, acknowledge uncertainty; to evade dogmatism and embrace ambivalence and contradiction; to engage in intimate conversation with one’s readers and literary forebears; and to uncover some unexpected truth, preferably via a sparkling literary style. Flexible, shape-shifting, experimental, as befits its name derived from the French (essai = “attempt”), it is nothing if not versatile.

In the United States, the essay has had a particularly illustrious if underexamined career. In fact, it is possible to see the dual histories of the country and the literary form as running on parallel tracks, the essay mulling current issues and thereby reflecting the story of the United States in each succeeding period. And just as American democracy has been an ongoing experiment, with no guarantees of perfection, so has the essay been, as William Dean Howells argued, an innately democratic form inviting all comers to say their piece, however imperfectly.

The Puritans, some of our earliest settlers, chose the essay over fiction and poetry as their preferred mode of expression. In both sermons and texts explicitly labeled “essays,” men like Cotton Mather and Jonathan Edwards articulated their religious and ethical values. Many later American commentators would take them to task for being sexually prudish, intolerant, and repressive. H. L. Mencken, in a scathing extended essay entitled “Puritanism as a Literary Force,” blamed that heritage for holding back American literature by overstressing behavioral proprieties while understressing aesthetics. Edmund Wilson wittily noted that Mencken himself was something of a Puritan. The bohemian wing of American literature, from Walt Whitman to the present, has engaged in protracted guerrilla warfare with Puritanism and offered itself as an alternative. On the other hand, Marilynne Robinson defends the Puritans from what she regards as a caricature of their positions. Say what you will about their rigid morality: these Puritan thinkers were highly learned, with sophisticated prose styles, and we are fortunate in having them set so high an intellectual standard for later American essayists to follow.

Skip ahead to the Founding Fathers, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Paine, all of whom seem to have been superb writers. In their treatises, pamphlets, speeches, letters, and broadsides, they tested their tentative views on politics and governance, hoping to move from conviction to certainty. Theirs was a self-conscious rhetoric influenced by the French Enlightenment authors and the orators of ancient Greece and Rome, as well as the polished eighteenth-century nonfiction prose writers of their opponent, Great Britain.

In the decades following independence, United States authors labored to free themselves from subservience to English parental literary influence and to establish a national culture that would sound somehow unmistakably American. Washington Irving, perhaps the first freelance American author to support himself by his pen, was ridiculed by British critics such as William Hazlitt for imitating the English periodical essayists. He, in turn, wrote an essay entitled “English Writers in America,” which began: “It is with feelings of deep regret that I observe the literary animosity daily growing up between England and America.” He went on to analyze the condescending travel accounts of English authors in America, which were then all the rage in Great Britain: “That such men should give prejudiced accounts of America is not a matter of surprise. The themes it offers for contemplation are too vast and elevated for their capacities. The national character is yet in a state of fermentation: it may have its frothings and sediment, but its ingredients are sound and wholesome; it has already given proofs of powerful and generous qualities, and the whole promises to settle down into something substantially excellent.” Edgar Allan Poe bristled at the canard that Americans were too materialistic and engineering-minded to produce literature: “Our necessities have been mistaken for our propensities. Having been forced to make railroads, it has been deemed impossible that we should make verse .... But this is the purest insanity. The principles of the poetic sentiment lie deep within the immortal nature of man, and have little necessary reference to the worldly circumstances which surround him ... nor can any social, or political, or moral, or physical conditions do more than momentarily repress the impulses which glow in our own bosoms as fervently as in those of our progenitors.”

But it was Ralph Waldo Emerson, our greatest nineteenth-century essayist, who sounded the alarm most famously in his speech “The American Scholar.” Acknowledging that up to then the Americans were “a people too busy to give to letters more,” he nevertheless prophesied that the time was coming “when the sluggard intellect of this continent will look from under its iron lids, and fill the postponed expectations of the world with something better than the exertions of mechanical skill. Our day of dependence, our long apprenticeship to the learning of other lands, draws to a close. The millions, that around us are rushing into life, cannot always be fed on the sere remains of foreign harvests.” He concluded by saying: “We have listened too long to the courtly muses of Europe ....We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak with our own minds.” It’s worthwhile remembering that this author who called for independence from foreign culture was probably the best-read person of his time and had imbibed not only most of British, French, and German literature but Eastern religious classics as well.

Emerson developed a kind of essay that was quirky, densely complex, speculative, digressive, and epigrammatic. He was part of that extraordinary flowering of literary culture in the mid-nineteenth century, the so-called American Renaissance, which included Nathaniel Hawthorne, Poe, Henry David Thoreau, Herman Melville, Whitman, Margaret Fuller, and Emily Dickinson. By the time it had run its course, there was no longer any doubt that America had itself a national culture. But there was more at stake than just the development of literary talent. The nation was facing enormous political and moral challenges from the twin oppressions of blacks and women. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which called for runaway slaves to be captured by northerners and returned as property to their southern slave owners, converted many of these writers to the abolitionist cause. Some of the most eloquent essays attacking slavery were penned by African Americans, such as Frederick Douglass and Martin R. Delany. They engendered an essayistic discourse on race that would be taken up by a distinguished lineage of black authors, including W. E. B. Du Bois, James Weldon Johnson, Zora Neale Hurston, Alain Locke, Ralph Ellison, and James Baldwin, continuing into our present day.

Meanwhile, women of the nineteenth century, still denied the vote and other rights, were barred from many professions, patronized, physically abused, and oppressed. It is remarkable how far back in America feminist voices were heard, from Judith Sargent Murray’s 1790 “On the Equality of the Sexes” to Margaret Fuller to Sarah Moore Grimké and Fanny Fern, reaching a high point in the suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s great essay, “The Solitude of Self,” and sweeping forward to the twentieth century. The essay, once considered a male province, has been nourished by the mental toughness and emotional honesty of so many bold, brilliant women in the last hundred years: think of Mary McCarthy, Hannah Arendt, Elizabeth Hardwick, Susan Sontag, Adrienne Rich, Joan Didion, Cynthia Ozick, Zadie Smith ....

Many of the essays chosen for this anthology address themselves specifically — sometimes lovingly, sometimes critically — to American values. (See, for instance, the pieces by George Santayana, Mary McCarthy, and Wallace Stegner, each taking America’s temperature.) But even those that do not do so have a secondary, if inadvertent, subtext about being American. E. B. White was an influential example of an essayist who conveyed, in a down-to-earth American tone, the average citizen’s preoccupations at home, while remaining aware of the larger challenges facing society.

In a United States where various groups have felt marginalized because of their ethnicity, national origin, gender, geographical location, or disability, members of these groups have increasingly turned to the essay as a means of asserting identity (or complicating it). Gerald Early, in his anthology Speech and Power, wrote: “Since black writing came of age in this country in the 1920s, the essay seems to be the informing genre behind it .... It is not surprising that many black writers have been attracted to the essay as a literary form since the essay is the most exploitable mode of the confession and the polemic, the two variants of the essay that black writers have mostly used.” The same could be said for other minority groups in American society, who have benefited the essay form immeasurably by adapting it to their purposes, enriching the American language with their dialect-flavored speech. They have contributed to the “cultural unity within diversity” ideal that Ralph Ellison envisioned for this country. At the same time, the American essay has taken a turn toward greater autobiographical frankness, thanks in part to their efforts.

Another skein of essay writing, of unarguable importance now that the planet finds itself endangered by climate change, is nature writing. In America, that tradition goes back at least as far as J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur and extends to John James Audubon, Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, Mary Austin, John Burroughs, Edward Abbey, Rachel Carson, and Annie Dillard, among others. We see in it an attempt to balance the factual and descriptive elements of flora and fauna with a fresh emotional access to wonder and awe. However alarmed these essayists may sound in their warnings of the threats to nature, there is still looming underneath an appeal to the original myth of America as the New World, a second Garden of Eden where humankind could finally get it right.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu