Is this the end of the road for the Democratic Party hopeful?

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Is this the end of the road for the Democratic Party hopeful?

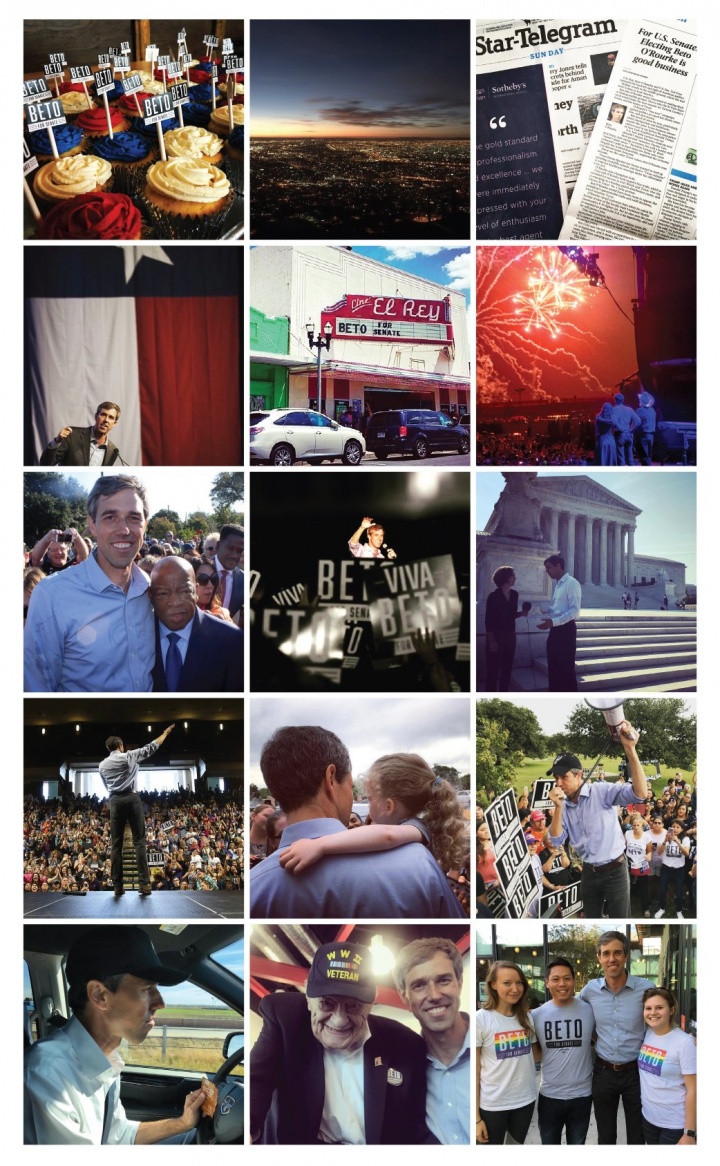

The view from the road, from Beto’s Instagram.

@betoorourke (Instagram)

John F. Kennedy was our first television president, Ronald Reagan the movie-star-in-chief. And now, under the reign of our first reality-TV leader, Beto O’Rourke may compete to become the inaugural POTUS of social media. From his first livestream hit as a congressman — a 2017 road trip to Washington, D.C., with a Republican colleague — to his viral clip in defense of kneeling football players, O’Rourke used online saturation to build a national brand at breakneck speed, defying Democratic Party pundits who said such exposure was peanuts in the grand scheme of politics. By the end of his Senate run, “Beto” was a logo on T-shirts in Brooklyn and a staple of newspaper headlines from Chicago to Australia.

It wasn’t just a matter of how good he looked on Instagram (even while having his teeth examined); it was his casual confidence that the more voters saw of him, the more they would like. It helped, too, that he emanated empathy and wit and utter indifference to decorum. (He cursed frequently and sweated so profusely that supporters dressed as “Sweaty Beto” last Halloween.) He is real in a very specific way, born of his upbringing in bilingual, unglamorous El Paso, his coming-of-age in cosmopolitan New York and his decision 21 years ago to return home. Many politicians can rouse a crowd — in fear, in anger, or in hope. But Beto is best in close-up, bridging gaps of ideology, ethnicity and class one on one.

His streaming videos, along with the epic road trips they captured while visiting all of Texas’s 254 counties, helped O’Rourke raise $80 million and brought him within 2.6 percent of stealing Ted Cruz’s seat last November — closer than any Democrat has come to statewide office in two decades. And Cruz was never supposed to be under threat. O’Rourke’s near-victory made people wonder what he could do on a more level playing field: the 2020 Presidential Election.

Months before all that, my ride with Beto began at El Paso Airport, where he arrived early on a Friday morning from a Dallas campaign jaunt. His friend Bob Moore, a former executive editor of the El Paso Times, then drove us to two West Texas town halls and finally, after a long stretch of desert, to Loving County, population 134, the smallest and second-to-last of the 254 Beto had pledged to visit. The goal was not to pack a stadium, as O’Rourke already had in beet-red Amarillo, but to “meet the people of Loving County, if we can find them.” In 2016, 58 of those people voted for Donald Trump, four for Hillary Clinton.

The first thing Beto did when we arrived in Mentone, the Loving County seat, was to disappear. “How do you lose a guy [in a town this small]?” asked Moore, looking across the single sandy intersection that passed for Mentone. Soon we spotted O’Rourke — tall and lanky, with that Kennedy jaw — stooping to enter a plain white house. We were welcomed inside by an older man named Stan, who warned us gently that he was a Republican. “That’s OK; you don’t have to vote for us,” said O’Rourke. He and Stan spent 15 minutes discussing immigration and more local issues — like the giant oil trucks, drawn by a natural-gas boom, that were cutting into the dusty patch of Stan’s lawn. “I’m impressed that you’re here,” said Stan.

Back outside, it was 105, shadeless and desolate. There was another house (empty), a courthouse (closed) and an aluminum-roofed convenience store (packed with oil workers buying six-packs). A woman at the register told O’Rourke that Mentone was “awful, awful and more awful.” She didn’t live in town. No one really did. There was no political playbook in which coming here made any kind of sense. Beto loved it.

No one who knew the young O’Rourke would have bet on him going into politics, never mind his looks or his pedigree. He was born in El Paso in 1972 to Patrick O’Rourke, a progressive Democrat who once served as county judge (a powerful executive position), and Melissa, a moderate Republican who owned a furniture business. Born Robert, 100 percent Irish American, he was called Beto as a toddler (a common nickname for Robert in this overwhelmingly Latino town). He met his closest friends as a young teen, in basketball camp.

“We were the least athletic, and we all liked music,” says Mike Stevens, who’s still close to O’Rourke, explaining why he and Beto and Arlo Klahr became fast friends. In basketball and in the rock band they soon formed, each had his strength. Beto “had the height” on the court and the pop sensibility on stage, making music that was “noisy and hectic, but still hummable,” says Stevens. “And he was a pretty clever songwriter.” O’Rourke was also a tech geek, dabbling in the bulletin boards of the internet’s infancy.

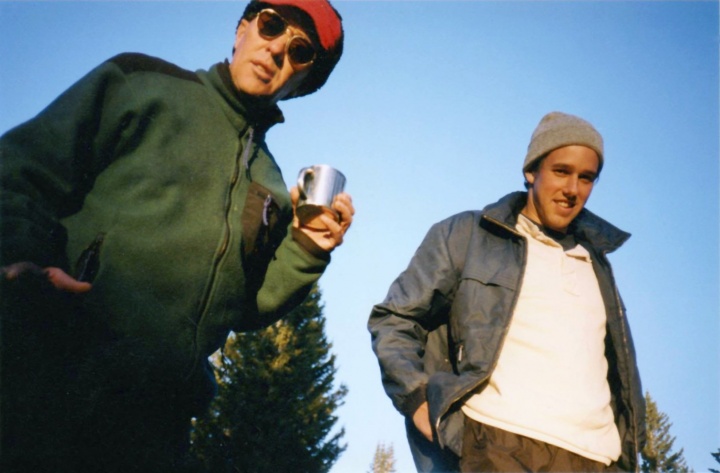

Beto with his dad, Patrick.

BetoForTexas.com

And yet, Beto inherited Pat’s venturesome spirit. “If we were at a bar,” says Stevens, “Beto’s the guy who’d say, ‘Let’s go for a 10-mile run tomorrow,’ and you’d say ‘Yeah!’” No one took it seriously, “but then at 8 a.m. he’s waking you up, saying, ‘Hey, let’s go!’”

O’Rourke went to boarding school in Virginia, followed by the College, with an internship for Texas congressman Ron Coleman in between (“my dad made me do it”). That’s when Beto started going as Robert. The campaign of Ted (né Rafael) Cruz repeatedly mocked “Beto” as a false nickname, but in fact Robert was the name that was tried on and temporary. “It’s more grownup, and nobody could say ‘Beto’ right in New York,” says O’Rourke. But “Robert” didn’t stick.

At Columbia, O’Rourke learned the power of storytelling; he wrote fiction and adored The Odyssey (he jokes he named his son Ulysses because he didn’t have the nerve to call him Odysseus). He also learned how to stick to schedules and, most importantly, how to straddle different social worlds. His artist friends knew him as the scruffy guy who got them into trouble for skateboarding through the dorm. But he also became co-captain of the crew team — which meant picking up boatmates in the team van, “hauling people’s asses out of bed,” as he puts it, just as he had for early-morning El Paso runs. (Pre-dawn group runs were a staple of his Senate campaign, too.) “It was surprising to me that someone who was creative and sort of a nonconformist was involved in this super-organized, rigorous discipline of rowing,” says Katherine Raymond, a college girlfriend.

Much has been made of Beto’s not-very-long-lived “punk-rock” band, Foss, which he formed while home from boarding school with Stevens, Klahr and Cedric Bixler-Zavala (who went on to front Mars Volta). But their El Paso scene was really more do-it-yourself than anti-authority. “He didn’t want to be a fake person,” says Raymond. “He was just riding around and connecting with people at shows. That’s consistent with what he’s doing now. I personally think running against Ted Cruz as a Democrat in Texas is pretty punk rock.”

O’Rourke describes the parallels more plainly: “You book your own stuff, you write your own material, you tell your stories in your own voice.”

Back in May, our first destination was a town hall at Fort Hancock H.S., an hour-long drive from El Paso along Texas’s far Western border with Mexico. The traffic quickly emptied out as I-10 shot through flat desert stubbled with creosote. Inside our SUV, O’Rourke rehearsed names and talking points — a ritual that wasn’t for the Facebook audience.

Beto meeting and greeting while running the International US-Mexico 10K in 2016.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection

But every Texas county is different, so O’Rourke quizzed his driver and resident expert, former newspaperman Bob Moore, on Fort Hancock’s local concerns. “What are the issues you know about?” he asked. “Agricultural issues are big,” said Moore. “Border issues, too. People forget that there is an international border crossing here.” Reports of a new child-separation policy were trickling in that week. We had just passed the exit for Tornillo, the border town where, a few weeks later, O’Rourke would be one of the first politicians allowed inside a tent city housing migrant kids. Unsurprisingly, his platform called for the kind of sane and compassionate immigration policy that could help El Paso thrive.

Arriving a bit late in Fort Hancock, O’Rourke spoke in the school’s gym to members of a 98 percent Latino student body. He described a nation divided between hubs of wealth that attracted talent and forgotten places that didn’t, making an example out of himself. “Born and raised in El Paso,” he said. “Grew up in that community — sometimes defensive, apologizing for who I was, where I was from, telling people, ‘Well it’s not that bad, but yes, I want to get out of here, I want to go somewhere else, I never want to come back home.’”

Twenty-five years ago, O’Rourke was a data point in the small-town “brain drain” he laments. After college he took a variety of jobs in New York — moving art, proofreading, programming for tech startups. He moved with friends into a half-empty factory building in trendy Williamsburg. Stevens and other El Paso friends followed. “We were just having a great time,” says Stevens. “But Beto told me, ‘I don’t want to spin my wheels.’”

O’Rourke remembers one long, sweaty subway ride to a publishing job in the Bronx, during which “this vision hit me of being in my truck, listening to the radio, having my windows down.” It was a flashback to his touring days — and a premonition of road trips to come. In 1998, he bought a truck for $1,000 and made the long drive back, with Stevens riding shotgun.

A couple of years later, O’Rourke started Stanton Street, an El Paso tech services company, with help from his parents. After the business spawned an online newspaper, Pat O’Rourke filed dispatches for Stanton Street from his frequent cross-country bicycle trips.

In 2001, Pat was biking near El Paso when he was fatally struck by a car. It was a devastating rupture for Beto, but also an inflection point. The younger O’Rourke had drifted in those early El Paso years; he was arrested once for trespassing and another time for drunk driving. But now that his mentor and taskmaster was gone, he had to grow up in his own way. “He’s liberated from his father’s shadow,” Stevens says, “this guy he had to live up to — but he also has to be more serious. I think it matured him even faster.”

Stanton Street pointed the way forward — indirectly. It was both an online chronicle of El Paso and, ideally, the kind of business that could improve O’Rourke’s hometown. El Paso was essentially half of an international metropolis (with Ciudad Juarez across the border), a hub of trade and immigration with a distinctive style and sense of pride, but also a place built on low-wage factory jobs — jobs that were rapidly fleeing across the Rio Grande. O’Rourke hoped businesses like his could raise the city’s wages and living standards. As a publisher in a politically connected family, he was well placed to meet like-minded reformers.

A couple of them were working for a transformative (but short-lived) mayor, Raymond Caballero. “I’d never heard someone in public life say we were a great city,” O’Rourke says, referring to Caballero. “To say, ‘We’ve got to live up to it and we’re not doing the shit we need to be able to do.’ As a young person that’s all you want … I wanted to be involved in something bigger.”

One of O’Rourke’s closest allies was former Caballero aide Susie Byrd. The day after my trip with Beto, Byrd took me on a hike up the dry hills behind El Paso. At the summit was an electrical tower and sweeping views of both El Paso and Juarez. Byrd reminisced about teaming up with Beto and others to join the city council, where they wrested control away from an entrenched old guard. (Another reformer, Veronica Escobar, just took over O’Rourke’s congressional seat.)

The reformers had hoped to transform El Paso into a new-economy hub, but Byrd concedes that they moved too fast; some of their development plans fizzled under fierce backlash. Yet O’Rourke showed a flair for taking the right risks, breaking the right rules. He considered running for county judge like his father, but the reformers nudged him to aim higher. So he ran in the 2012 primary against another old-guard pol, eight-term congressman Silvestre Reyes. His race was considered unwinnable — until it wasn’t. Many felt that Reyes had lost touch with his constituents, and O’Rourke knocked on every door and took every town-hall question. Once in Congress, he defied Democrats by refusing to spend hours on the phone raising money, and he eschewed high-profile committees in favor of unsexy Veterans Affairs. He also kept holding those little town halls.

Beto speaking with College students at Low Rotunda in February.

Eileen Barroso

Leaving Fort Hancock behind schedule, we scarfed down sandwiches on the road, throwing the trash under our seats. The desert sprouted hills; dust devils swirled in the distance. An hour later, we crossed into the Central time zone and entered Van Horn, a photogenic desert town that could almost pass for the nearby arts enclave of Marfa if you squinted hard in the unforgiving sun. The Cactus Cantina, just on the cozy side of sleek, greeted Beto with green-chile pizzas and a packed crowd north of 50. Turnout in O’Rourke’s 252nd county was better than expected.

People had come from as far as Austin, but the audience wasn’t uniformly leftwing, and O’Rourke struck a bipartisan note. “I know that the Democratic Party as well as the Republican Party do not have a monopoly on good ideas,” he said. If we fail to listen to one another, “we are going to fail one another.”

The first question, from local county judge Carlos Urias, returned to partisan reality. “This is a red state,” he said. “Talk to me. You’re behind in the polls; what do you think?”

O’Rourke smiled. “Great question from the judge: ‘How in the heck are you gonna pull this off?’” Everyone laughed, but Beto went on to talk about Texas being “a nonvoting state,” about his message of unity and civil debate being a winning one for people sick of President Trump’s divisive insanity.

Throughout my reporting, as the polls swung back and forth but never showed O’Rourke in the lead, I heard variations on the same sentiment: If he gets within five points, he will have won. He will have proven that the right Democrat can finally compete in Texas. On that front at least, O’Rourke succeeded. The day after his loss, pundits put him on the list of probable 2020 presidential contenders. Two independent “Draft Beto” movements formed in December.

But then, skepticism crept in from all sides. Was he ready? Was he liberal enough? Was he for real? Shirking expectations, O’Rourke went on a solo road trip, blogging the whole way and avoiding the early primary states. On social media — his home turf — some derided him as a self-styled Kerouac plagued by un-presidential self-doubt. And sure, it was easy to mock his lonely confessions and his aw-shucks encounters with Kansas barflies. But he was also being vulnerable, radically honest — almost raw. He seemed genuinely not to care about the rules of perception, but he did seem to want to run. He told Oprah as much in early February, teasing an imminent decision in a public interview. What are his chances? People want authenticity, we know. Is Beto’s brand of it the kind they are looking for? When it comes to politics, stranger things have definitely happened.

In November, Beto won six votes in Loving County — two more than Hillary did. Did Stan vote for him? Letitshia, the woman at the store register, probably did. She had told him the oil trucks were causing fatal accidents; the water was poisonous; the police wouldn’t help with her domestic dispute; the toxic land might have something to do with the lump in her breast. She regarded the tall handsome stranger running for Senate as more of a confidante than a savior. The last thing she said was, “Treat people like humans.”

Moore and I and a few campaign workers rode back to El Paso from Mentone, but Beto didn’t. It was the Friday before Memorial Day, and he was joining his family at his in-laws’ ranch in New Mexico. He put in a quick call to his wife, Amy, shortly before leaving dusty Loving County. “We had really good town halls,” he reported. “I’m not too far behind you guys. They calculate five and half hours but I can cut that down.” Amy warned him to drive safely. “I will,” he said. “I’ve got tunes. I kind of lost my voice a little bit. I just need to drive and be quiet for a few hours, and I’m down for that. It’ll be good.”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu