Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Literature Humanities and the Democratic Moral Imagination

This column is part of an ongoing series offering insight into the Core Curriculum.

Core Curriculum director Larry Jackson

Emma Asher

Columbia College requires all its students to study literature, philosophy, art and music in its Core Curriculum. While these courses sit within a broader framework of liberal arts requirements — including the fifth Core course, Frontiers of Science, which was added in 2004 — the humanities occupy a prominent place in our students’ general education. In the next few issues of CCT, I’ll explain why that is and discuss the unique benefits of each Core course.

I’ll start where all of our students begin their Columbia journey: Literature Humanities.

About a month before they arrive on campus, incoming first-years begin reading Homer’s Iliad. In its pages, they encounter the violence of war, unjust social hierarchies and morally complex relationships between siblings, husbands and wives, parents and children, and guests and hosts. To read the Iliad is to travel by way of imagination into a world that can seem both strange and familiar.

I want my students to take note of literary devices, such as Homer’s well-known epithets and similes. But it is the ability to cross over from our world into that of the characters that interests me the most. That crossing is the work of our moral imagination.

Through literature, we can enter into the lives and experiences of people who don’t look like us, think like us or live like us. From this sojourn in the lives of others — and its limits — we learn about ourselves and our values.

Empathy may be a consequence of this imaginative crossing, but it is hardly the only one. I discover the limits of my sympathies in Achilles, whose rage, described as god-like, resembles nothing so much as a child’s petulance until, at last, it becomes murderous revenge. Like many modern readers, I instead empathize with Chryseis and Briseis, the trafficked women whose fate is so callously decided by Agamemnon. As a father, I feel the pride and affection for my children that Hektor shows for his son, Astyanax, in one of the epic’s most moving scenes. But our identification ends there, because, unlike the Trojan warrior prince, I want my children to know only the joys of peace, not the glories of battle.

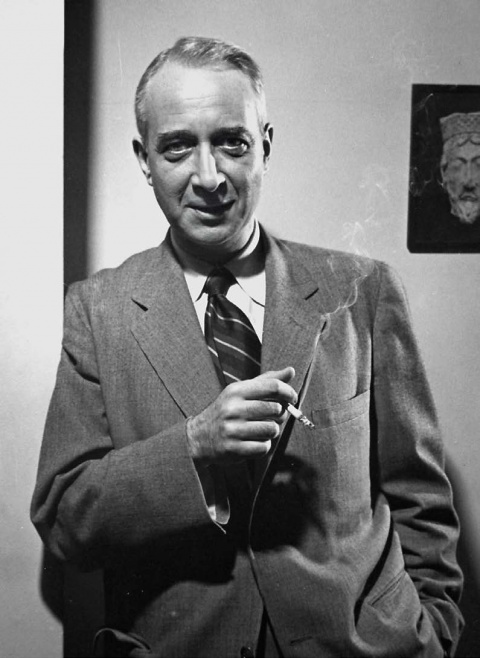

Lionel Trilling CC 1925, GSAS’38

TIME & LIFE PICTURES / GETTY IMAGES

You don’t have to agree with Trilling’s politics to believe that moral imagination and the sentiments it fosters are indispensable to democracy. The intellectual tradition to which Trilling belonged, beginning with Ralph Waldo Emerson, long championed literature for its ability to inspire the sociable feelings on which democracy depends. Frederick Douglass saw literature as crucial to the abolitionist struggle: “One flash from the heart-supplied intellect of Harriet Beecher Stowe could light a million camp fires in front of the embattled host of slavery, which not all the waters of the Mississippi, mingled as they are with blood, could extinguish.” Walt Whitman, who served as a nurse during the Civil War, also cared for fugitive slaves, Native Americans, recent immigrants and wounded soldiers in his poetry: “And these tend inward to me, and I tend outward to them, / And such as it is to be of these more or less I am, / And of these one and all I weave the song of myself.”

If literature does cultivate the moral imagination on which democracy depends, then we cannot limit our reading to works from the past or a single tradition, but rather should explore a wide range of texts and perspectives, as students in Lit Hum do with the recent addition of works by Suzan-Lori Parks, Claudia Rankine and Myung Mi Kim. The measure of students’ success in Literature Humanities will be the distance that they cross in their moral imagination, and the realization that they, like Whitman, contain multitudes.

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu