CCT: What drew you to the YA category?

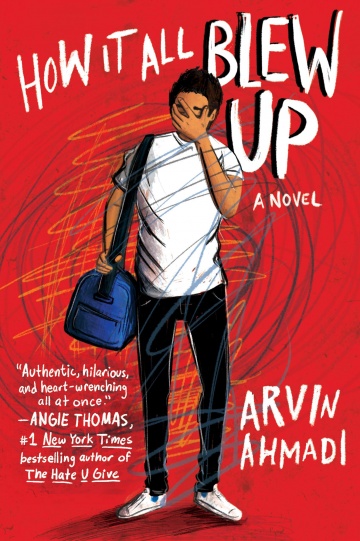

Arvin Ahmadi ’14

JOE POWER

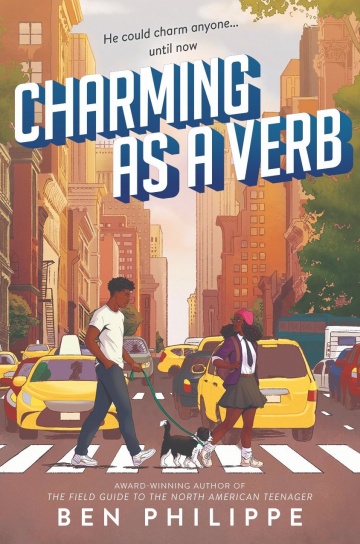

Ben Philippe ’11

ASHLIE BUSONE

Ahmadi: Ben is right. I think nothing is off-limits in YA. But also like Ben, I didn’t know that I was writing “Young Adult” literature. Two of my favorite books in high school were Catcher in the Rye and It’s Kind of a Funny Story and I had no idea I was reading YA; I just knew I was reading good books, books that I loved, books that were extremely voice-driven, books that I identified with. It’s the freshness of the voice and approach to adult experiences that I love about YA. I heard an author say something like, “We never grow out of our teenage selves; we just develop armor.” And that’s the great thing about the teenage point of view. It’s these raw experiences, these raw emotions that we will continue to feel for the rest of our lives. We’ll always be that person; it’s just that adulthood muffles a lot of our emotions and the way we feel we have to act and speak in the world.

CCT: What sparked your interest in writing?

Philippe: When I was younger I didn’t latch onto the title of “writer”; it just wasn’t a thing I felt people did as a career. You were either a doctor or a lawyer, and in the case of my family, that’s where the list ends. I did dabble in fan fiction — it was the awkward after-school horrible fan fiction — making the characters of Buffy the Vampire Slayer kiss. It wasn’t until college that I took a creative writing class. The idea when I came to the College was that I was going to become a powerful Hollywood agent; Entourage was big at the time so I was going to become Ari Gold, which meant a double degree in film studies and economics. In my first semester I had seven classes, and only one elective fit. It was a creative writing beginners’ workshop, and I loved it; it was my favorite part of the semester by far. Little by little, I took more fiction workshops and seminars. Then when it came time to graduate I was told, “You would need to stay an extra year to even have a concentration in economics, but you’ve completed more than the creative writing major already,” so I was like, “Oh, my transcript tells me I’m a writer.”

Ahmadi: I had always been a writer, even if I didn’t know it. I wrote my first book when I was 10 — The Adventures of Jack and Skipper. It was about a boy named Jack and his dog, Skipper, and some great mystery they were trying to solve. I wrote about three chapters of it and started querying literary agents because I was so convinced that I had written the great American novel and it needed to be published. Of course, none of those agents signed me; I don’t think many of them even responded! So then I moved on to emo poetry and from there to journalism. So I’d always done bits of writing for fun, whether it was my first novel, or poetry or journalism, but I never attached myself to the word “writer.” It was senior year of college when I started writing my first book, Down and Across, which was largely inspired by my own feelings of failure at the time and just feeling intimidated by everything that lay ahead in the rest of my life. I was graduating and had to go be an adult, and I had a lot of questions swirling in my head about that. So that sparked that book, which I did not expect to propel me into a career, but here I am, and I couldn’t be happier.

CCT: Both of your most recent books have featured young men of color. Do you see the industry encouraging the creation of more diverse stories that break out of the mold of what many people think “YA lit” is?

Ahmadi: I would give credit to the audiences and not the industry. I think that there is a hunger for more stories from the entire spectrum of backgrounds and of sexualities, and of every form of diversity. And the industry is a business that reacts to what people want. So the industry is changing, but it’s not because it just woke up one day and said, “You know, I want to be better; I feel like telling more diverse stories today.” People have been demanding it for a long time, especially marginalized young people who want to feel seen and represented on page, and finally the industry is reacting to that.

Philippe: We’ve done a great job of empowering young people to question everything. So you throw The Great Gatsby or Gilgamesh at them and say, “This is the greatest work of literature,” and they just stare back at you and ask, “Why?” They look for themselves in the things they read now and they look for ripples of what the existence of a particular work means for the world. It used to be if a book existed, you didn’t question how it affected the readers, but young people today really engage with it in an amazingly intense way.

CCT: What’s the writing process like for you?

Philippe: That’s the question I’ve told so many lies about on panels! I want to sound like I know what the hell I’m doing but I truly do not. I think more about my characters now than I used to, and I try to live in the story before I start writing. I like to nurture the story in my head and stay in the world for a bit until it’s the one thing I can focus on.

Ahmadi: There is no day-to-day; some days I’m feeling triumphant and I write 3,000 or 4,000 words, and other days I edit a sentence 18 times over. But the part of my process that I’ve homed in on in the last couple of years is editing and revision. I used to be really precious about my first drafts and as a result I would write a first draft laboriously and then not want to change anything when I got feedback. And that has completely changed — now I crave feedback, and I crave notes. I’m willing to rewrite until I get the story right.

Philippe: I’ve also stopped feeling the need to be clever. I have old Word doc drafts where every sentence sounds like a tweet; it’s just trying to make an invisible audience laugh or smirk. But little by little I’ve found the appeal in perfunctory, small sentences that move the story forward. Also, deadlines! When I know my editor is expecting a novel, that date becomes kind of red on the calendar and then you get the first draft. But the first draft is the skeleton; it’s not the book, it’s the thing you need to cobble into a novel.

Ahmadi: I second you on deadlines. When I’m working toward a deadline I’m not overthinking it, I’m not being precious with my words. Nothing gets me working more than a deadline!

CCT: When writing, do you draw from your own experiences and/or from the experiences of other young people in your life?

Ahmadi: I just try to put myself in an authentic headspace when I write YA. As a teenager I certainly had blockers that prevented me from being fully myself or saying exactly what was on my mind, but I felt more intensely. I think that mindset encourages me to be more authentic and have more freedoms when I’m writing. It’s a symbiotic relationship; my YA writing encourages me to be a better adult and, as an adult, thinking more authentically makes me a better YA writer. It’s what I hear a lot of my friends who write YA and kid lit in general say: “I write the books I wish I had as a young person.”

Philippe: I think we underestimate how teenagers think. People act like if you’re writing about a teenager, they have to only think about prom and the popular kids. And that may be true, but I’m 32 and I think about whatever the adult version of prom is, like literary awards, and I think about people I like and dislike, so the mindset isn’t that different. But it’s also fun to write about characters who take risks, and younger characters are at that age in which you often feel invulnerable in an interesting way. It’s an age at which you’re still finding yourself, you’re trying on all these outfits and personalities; I don’t think anyone is ever as mean as they are when they’re a teenager! And there’s a fun-ness to embracing that freedom.

CCT: A big part of life as a YA author is social media interaction and audience interaction at conventions. What’s it like balancing your public persona and private life?

Philippe: I think the idea that [some] authors are awkward or not well adjusted is false, because all the YA people I’ve met at conventions and book events are incredibly poised and charming, and incredible on stage. I think because of social media it’s harder to make a distinction between your real self and your performative self; the more you have to take and perform in your everyday life, the more it coalesces into one person.

Ahmadi: I think we have author lives and writer lives, and our author lives get to be on Twitter and Instagram and interact with readers at book festivals and in signing lines and on panels. But my writer life involves waking up and trying to remember how to write. There’s a lot less confidence and a lot more vulnerability in the writer life, whereas the author life is that performative piece where we talk about our process and our characters. And I love all of that. It helps fuel the writer stretches when I’m struggling to churn out words, but both sides go hand in hand. I think the writer piece is the struggle and the author piece is making sense of the struggle.