Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Patrick Radden Keefe ’99 Dishes About Empire of Pain

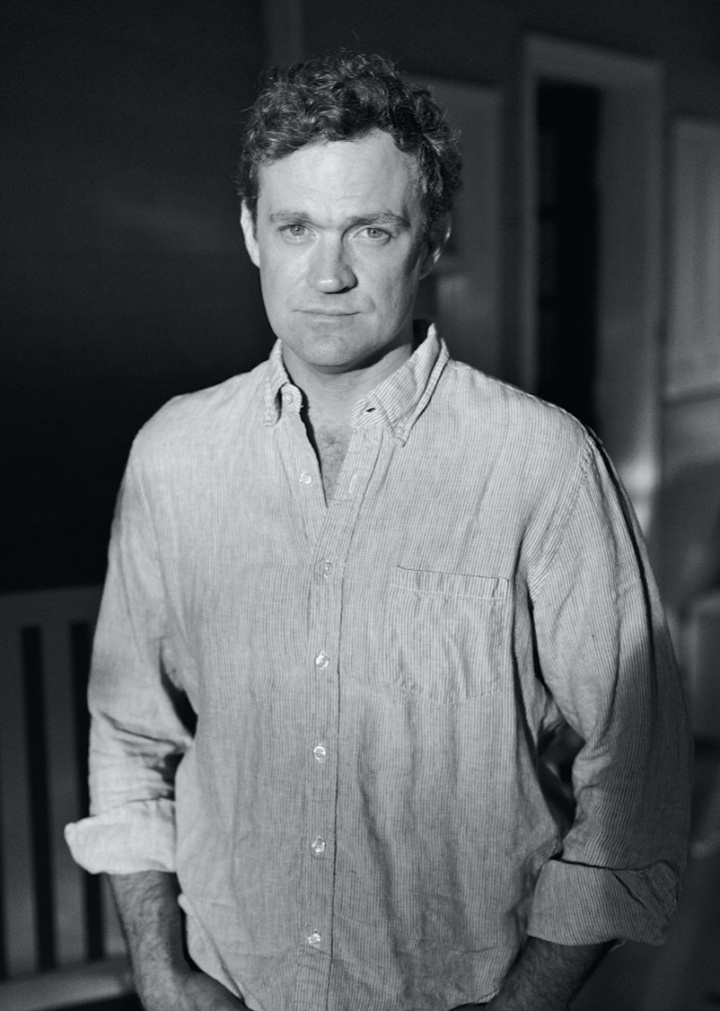

Philip Montgomery

Now Radden Keefe is back with another investigative turn, Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty. The book is a devastating portrait of the Sackler family, once primarily known for its philanthropy, now more notorious as the owners of Purdue Pharma. Through a study of three generations of Sacklers — along with an exploration of the tactics they employed in making and marketing OxyContin — Radden Keefe examines the family’s role in perpetrating the opioid epidemic in the United States. Earlier this month, the New Yorker staff writer spoke with CCT about his aspirations for Empire of Pain, the most striking revelations he uncovered and what it’s like to write a book when the family at its center chooses to remain silent.

You’ve had a busy couple of years! How has that been for you? Do you ever take a break?!

It has been a busy stretch, but having a global pandemic basically cancel all my plans for 2020 certainly cleared up my schedule and allowed for some productive writing time. I was pushing hard right up to the moment the book came out and then promptly came down with Covid. I’m fine; it was a mild case and I’m already feeling much better. But it might have been a sign that it’s time to slow down.

You first wrote about the Sacklers and the opioid crisis in a New Yorker article in 2017. How did you come to the story, and when were you persuaded there was a deeper and book-length story to tell?

You first wrote about the Sacklers and the opioid crisis in a New Yorker article in 2017. How did you come to the story, and when were you persuaded there was a deeper and book-length story to tell?

I came to the story through reporting I had been doing on narcotrafficking organizations in Mexico. I noticed that they were exporting more heroin to the U.S. and wondered why. The answer turned out to be the huge existing market of people in this country who had started using prescription painkillers and eventually graduated to heroin. That got me interested in the opioid crisis, and I was startled to discover that one of the key culprits in the crisis, Purdue Pharma, which manufactures OxyContin, was owned by the Sackler family, a prominent philanthropic dynasty that has given generously to art museums and universities, including Columbia.

Can you paint a picture of the reporting that went into the book — who were the types of people you were speaking with, what kind of paper trail were you following? And how did you work around the fact that the Sacklers declined your requests for interviews?

There’s a certain hubris in writing a book about a family when nobody in the family will speak with you, and indeed, when some members of the family are threatening to sue you if you write the book. But I like a reporting challenge, so I interviewed more than 200 people, including dozens of former Purdue Pharma employees and people who have known the Sacklers socially, or worked for them. I spoke to housekeepers, doormen, even a yoga instructor who worked for the family. In addition, I drew on tens of thousands of pages of documents, which had been produced in the thousands of lawsuits against Purdue and the Sacklers, or leaked to me. In that way, despite their lack of cooperation, I was able to tell the story of three generations of this family largely using their own words.

Readers might be surprised to learn that the first third of the book is spent with the family patriarch, Arthur Sackler, who died before OxyContin was developed. What about his story was relevant to understanding his family’s later decisions?

Arthur was a genius — a fascinating, protean figure who revolutionized pharmaceutical marketing in the 1950s and 1960s. He was sort of the Don Draper of medical advertising, and what I found when I delved into the history of his business interests (and of his philanthropy) was that much of what would come later, with OxyContin in the 1990s, was prefigured in the life of Arthur Sackler.

This is not just a family saga and a book about the pharmaceutical business; it’s also a crime story.

What in your view are some of the most striking decisions that Purdue Pharma and the Sackler family made around marketing OxyContin that opened the door to its abuse?

Humans have known for thousands of years that medicines derived from the opium poppy can have extraordinary therapeutic benefits but can also be potentially addictive. When Purdue launched OxyContin in 1996, the company did so with a very explicit strategy — directed by the Sacklers, who were running the company at the time — to persuade American physicians that this drug was not, in fact, addictive. They sent an army of sales representatives out across the country to meet with doctors and convey a message: that when prescribed by a doctor for pain, OxyContin was addictive “less than 1 percent of the time.” This proved to be a very compelling marketing hook — the drug would end up generating $35 billion in revenue — but it was also a lie. We have been living with the consequences of that con ever since.

Your reporting shows the Sacklers knew more than they admitted about how addictive OxyContin was. What was some of the earliest evidence that they’d learned about the damage it could cause, and yet continued to encourage its use?

The Sacklers and Purdue Pharma have long maintained that they only learned in early 2000 — four years after its release — that there were major problems with abuse and diversion of OxyContin. I was able to establish an extensive paper trail dating as far back as 1997 that there was awareness at very high levels of the company that there was indeed a big problem. Another company, and another family, might have responded differently to those early reports, but Purdue and the Sacklers chose to suppress the truth.

Empire of Pain doesn’t have a “neat” ending, in the sense that litigation around the opioid crisis is ongoing. Where do you see this book fitting into the larger story of how the Sacklers or Purdue Pharma is being called to account? What would you like for readers to take away?

One major theme of the book is impunity for the super elite, so it may only be appropriate that from a justice-and-accountability point of view, the ending has some irresolution. It’s important that readers remember that this is not just a family saga and a book about the pharmaceutical business; it’s also a crime story. The Sacklers’ company pled guilty to federal crimes in 2007, and again in 2020. In the interim, the family took some $10 billion out of the company, and yet they have faced no commensurate reckoning. No book can provide a substitute for real accountability, but I do hope that I’ve created an historical record of the decisions of this family and their company, and the dire legacy they leave behind.