CCT recognizes the toll the Covid-19 pandemic has taken on the College community.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

CCT recognizes the toll the Covid-19 pandemic has taken on the College community.

ALYSSA CARVARA

CCT recognizes the toll the Covid-19 pandemic has taken on the Columbia College community. If you know of a College graduate who died of the coronavirus, please indicate in an obituary submission so that we may include them in this feature, which is updated monthly. Obituaries are listed chronologically, and new additions are noted with an asterisk (*).

A writer with interest in television and film, Williams believed that positive LGBTQIA+ portrayals on American television contributed to increased acceptance. After moving to India in 2018, he worked hard to get such shows produced there, driven by the belief that if Indian television shows featured openly gay lead characters, it might help to accelerate change in cultural attitudes.

Williams’s older brother, John, noted that his brother “really believed in the power of the media to change the way people thought about certain disfavored populations.”

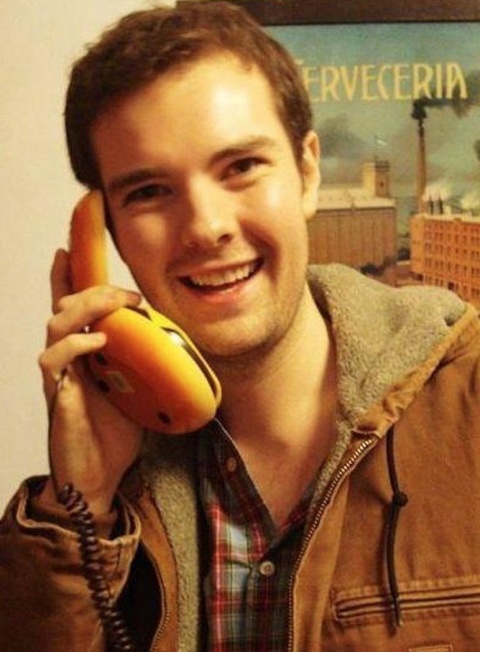

Born on June 30, 1985, in Florence, Ala., Williams grew up in nearby St. Florian until his mother died in a car accident in 1992 and his father died by suicide in 1995. Williams and his brother went to live with their aunt and uncle, Sharon and Bill Alexander, in East Amherst, N.Y., near Buffalo.

At the College, Williams majored in English, enjoyed composing observational essays and especially admired Joan Didion. He edited Inside New York, a guidebook to the city; sang for Notes and Keys; wrote and edited The Blue and White; and co-wrote the 2008 Varsity Show. “He was a campus character, a big, tall, funny guy who always had a good story to tell,” Laura Kleinbaum ’08 told The New York Times.

Following graduation, Williams became a personal assistant to writer Daphne Merkin. In order to better understand his childhood, he also began an oral history project by interviewing his parents’ friends in Alabama.

And he began seeing the world. Williams lived for a time in Buenos Aires and in Los Angeles. “He was really into getting airline points, and he would make random trips to random cities to get them,” Kleinbaum said. “You’d be texting with him, and he’d be, like, ‘Oh yeah, I’m in Shanghai.’”

It was on one of Williams’s trips, a vacation to India in 2017, that he met Ayush Thakur, whose hatred of intolerance and commitment to gay rights was as deep as his. Williams moved to New Delhi in 2018 and became engaged to Thakur a year later.

Williams was known for his easy wit, ability to connect with others, talent for writing, fierce commitment to gay rights, and devotion to his family and many friends. His passions included the Muppets, the color orange, Lady Gaga, candy of all types and driving a convertible on a sunny day in Los Angeles.

The coronavirus pandemic struck India particularly hard and overwhelmed the country’s medical system. When Williams tested positive for Covid-19 on April 24, he was among the few able to find oxygen and a hospital bed in the Delhi region thanks to his network of friends. But he died four days later.

Williams is survived by Thakur; his brother; his sister-in-law, Eliza Borné; and the Alexanders. Memorial contributions may be made to UNICEF’s Covid-19 Indian Relief Effort or to GLAAD.

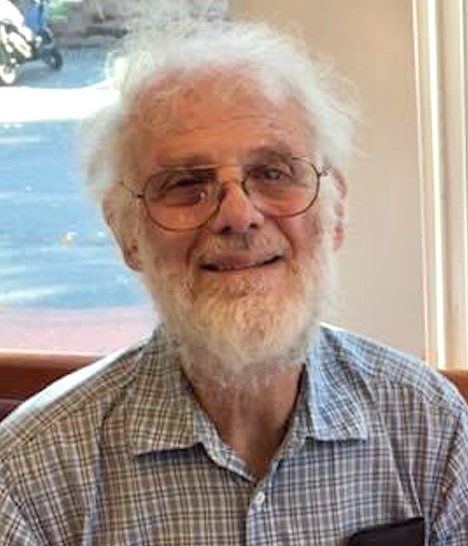

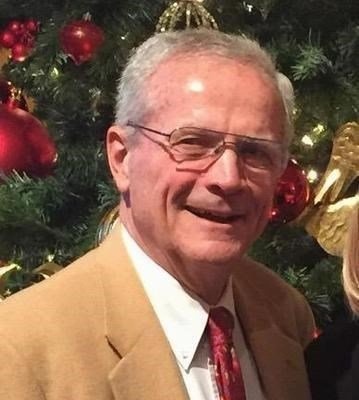

Kopperman was head of the mathematics department at The City College of New York (CCNY), but he was far more than a mathematician. A lifelong learner, educator and family man, he loved travel, nature, astronomy, exercising, bicycling, movies and camping, crisscrossing the United States and Canada several times. He fixed his own cars and learned and implemented an entire DIY-homeowner’s set of skills.

When asked once if he was prouder of having lectured at Oxford or having single-handedly reroofed his home, he declared it to be the latter.

Born on February 17, 1942, in New York City, Kopperman’s love of travel arose from childhood years spent living with his family in Bogota, Colombia. He blended his passion with his work by serving as visiting faculty or lecturer throughout his career, including time in Venezuela, California and England, and regularly traveled worldwide to write papers with colleagues.

Kopperman graduated from Forest Hills H.S., majored in mathematics at the College and earned a Ph.D. in mathematics in 1965 from MIT. He also earned an M.A. in 1984 in psychology from CCNY.

Kopperman began his teaching career at the University of Rhode Island, where he met his first wife, Sandra Baldwin, and founded the crew team, which exists to this day. In 1967 he joined the faculty at CCNY, where he stayed until his 2013 retirement as mathematics department chair. While he started in academia as a logician, he changed disciplines to topology in the late 1970s and became an important figure in that field.

He co-authored more than 75 academic papers and a graduate textbook, Model Theory and its Applications. He sat on the editorial board of the journal Topology and its Applications from 1998 until his death, and founded the New York Seminar on General Topology and Topological Algebra, which is still active.

Following his divorce in 1975, Kopperman opted to be the primary caretaker of his two children, an unusual choice in the mid-1970s. In 1979, he married Constance Hodapp Picciano, and together they raised a blended family of five.

In addition to his wife, Constance, Kopperman is survived by his brother, Paul; son, David, and his wife, Yesenia; and daughters, Susan Picciano, Leah BC’89 and her wife, Valerie Lieber, Amy Picciano and her husband, Mark McIntyre, and Gail Picciano. Memorial contributions may be made online at CCNY (select “Division of Science” in the designation menu and note “for the Math Department Discretionary Fund in memory of Prof. Ralph Kopperman” in the Comments box) or mailed to The Foundation for City College, 160 Convent Ave., Shephard Hall 154, New York, NY 10031.

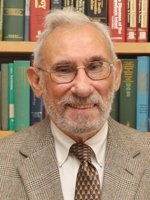

Rabbi Lerner was a strong, dynamic and creative leader who regularly bucked significant opposition to achieve progressive Jewish goals and attracted many people to Judaism.

“When I entered the rabbinate, it was to make more Jews, although I didn’t realize then that it would be from scratch,” he told the Jewish Standard, a newspaper in Teaneck, N.J., in 2015.

Rabbi Lerner grew up in the Grand Concourse neighborhood of the Bronx, a child of immigrants who came from Ukraine after WWI; he graduated from Bronx Science. A history major at the College, he was editorials editor at Spectator in his senior year and graduated Phi Beta Kappa; he also was a member of the Senior Society of Sachems. He studied ancient history at the University of Iowa, where he met renowned rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who saw Lerner’s devotion to Judaism and urged him to apply to The Rabbinical School at the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS).

Ordained in 1967, Rabbi Lerner increased the Hebrew school hours at Temple Israel of Riverhead, N.Y., and brought the synagogue into the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism. He served at Town & Village Synagogue in Manhattan for eight years, speaking out about the Vietnam War and Watergate and leading one of the first synagogue-based draft counseling services in the United States.

Rabbi Lerner was a leader of the movement to make Conservative Judaism egalitarian, expanding women’s roles starting in the early 1970s at Town & Village and in his next synagogue, the Jewish Community of West Hempstead, N.Y. During his tenure, women became counted for a minyan — the 10 people who must be present to begin a Jewish prayer service. Lerner later served as rabbi as Temple Emanuel of Ridgefield Park, N.J., now known as Kanfei Shahar. He also was the editor of Conservative Judaism, the quarterly journal of JTS and The Rabbinical Assembly.

Rabbi Lerner’s greatest calling, however, was bringing in newcomers and returnees to Judaism. He founded the Center for Conversion to Judaism at Town & Village, where he converted more than 1,800 students and created new Jewish families. He and his wife, Anne Lapidus Lerner, an emerita professor and vice chancellor at JTS, welcomed students into their home, and Rabbi Lerner modeled Jewish life for his students with his wit, storytelling and gastronomic gusto.

In 1994, Rabbi Lerner wrote in the magazine Masoret that in addition to introducing Judaism to new people, teaching would-be Jews-by-choice often brought “the awareness that a life has taken on new meaning with the discovery by the non-Jew, or rediscovery by the Jewish partner, of Judaism. In fact, “One of the special attractions of this work is that it frequently brings back people with Jewish roots who seek to reconnect and embrace a heritage abandoned a generation, or even centuries, ago.”

He also endowed a fund at the Spectator Publishing Co., some of which will be used for an annual Stephen C. Lerner Award for a student reporter for outstanding investigative or data journalism.

Rabbi Lerner is survived by his wife, Anne; brother, Irwin LAW’57, and his wife, Doris; son, Rabbi David ’93, and his wife, Sharon Levin; daughter, Rahel Lerner ’00 and her husband, Adam Gregerman; and five grandchildren.

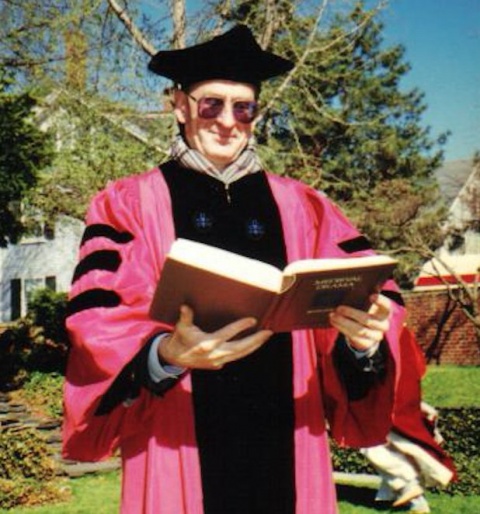

Materna was a successful trusts and estates attorney, but his proudest day had nothing to do with the legal profession. On May 17, 2005, he marched in the Alumni Parade of Classes in full academic regalia, then attended the graduation of the third of his daughters, Janine ’05. Materna, accompanied by his wife, Dolores, and daughters Jodi ’99 and Jennifer ’02, became the first alumnus to have three daughters graduate from the College.

“Thankfully, we had beautiful weather. It was a thrill for my daughters and me!” Materna said in a CCT Class Note.

Materna was born in Garfield, N.J.; he earned a J.D. from the Law School and focused his legal career on trusts and estates planning. He began with Chadbourne, Park, Whiteside & Wolff in 1973 and moved to Finley, Kumble, Wagner, Heine, Underberg, Manley, Myerson & Casey in 1980. Five years later he was named partner and head of the Trusts and Estates Department of Newman Tannenbaum Helpern Syracuse & Hirschtritt. In 1990 he moved to Shapiro Beilly Rosenberg Aronowitz Levy & Fox and in 2004 to Soloman Blum Heymann before launching the Law Office of Joseph A. Materna, Esq., in 2014.

Materna was a member of myriad professional organizations and was a lecturer in trusts and estates law as well as an expert witness in field court litigations. He was published in The Arthritis Reporter, writing about wills and tax law.

He received numerous honors throughout his career, most recently being honored by the Top 100 Registry as the 2020 Attorney of the Year in the State of New York. He held the Peer Review AV Rating from Martindale-Hubbell for more than 25 years and since 2010 had also possessed the Highest Possible Peer Review Rating in Legal Ability and Ethical Standards. In 2017 he was presented with the Albert Nelson Marquis Lifetime Achievement Award by Marquis Who’s Who.

Materna was named Top Trusts & Estates Attorney in New York City by Avenue Magazine; Top 100 Trusts & Estates Attorney in New York State by The American Society of Legal Advocates 2014–present; and Top 10 Best Estate Planning Attorneys in New York for Exceptional and Outstanding Client Service by the American Institute of Legal Counsel – 2019.

Materna enjoyed traveling and vacationed with family in nearly 50 countries; he also enjoyed telling jokes and delivering speeches and toasts. He is survived by his wife of 45 years, Dolores; daughters; brothers, Thomas and Kevin; and son-in-law, Tad Davis.

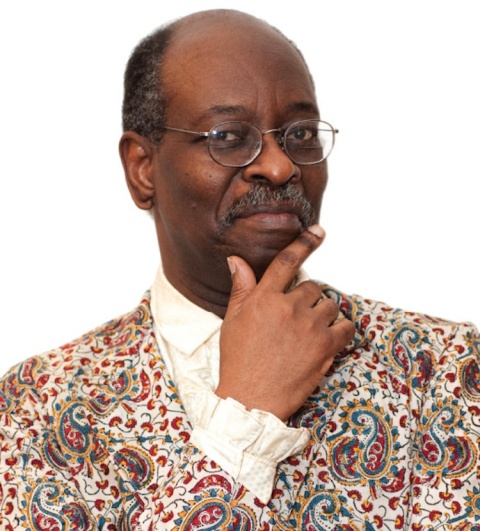

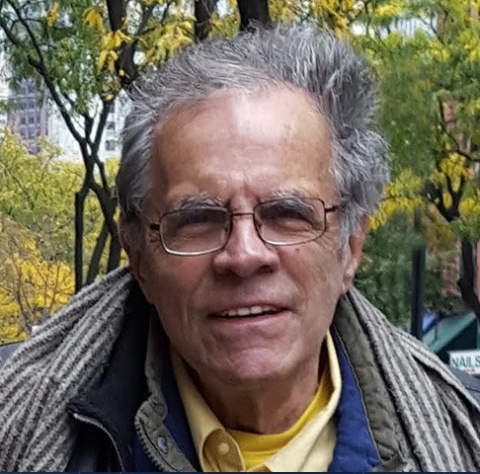

Davis’s four years at Columbia had a tremendous impact on his life, helping to shape him into a lifelong advocate for social justice. He was a caseworker for the NYC Department of Welfare (later Social Services) for 30 years and a fixture in the trade union movement, a shop steward at AFSCME Local 371 and a member of its executive committee, and a local delegate to the NYC Central Labor Council.

Davis grew up on a 49-acre farm in rural Pitcher, N.Y., the oldest of seven children who worked the farm to supplement the family income. His working-class upbringing amidst poverty-stricken neighbors helped shape his sense of justice. Accepted to both Harvard and Columbia, Davis chose the latter because of a scholarship offer. His experience as part of a diverse community and student body during the early 1960s activist upsurge of the Civil Rights and anti-Vietnam war movements made a lasting impression.

After graduating with a degree in psychology, Davis worked for the NYC Department of Welfare but was soon drafted into the Army. He was stationed at a military hospital in Germany, where he worked with soldiers with mental health issues. Following his discharge, he traveled across Europe before returning to the Department of Welfare and becoming a caseworker for the city’s adult, family and homeless populations. Upon his retirement in 1995, he was the tuberculosis unit supervisor at the Bellevue Hospital men’s shelter.

In the early 1970s Davis started his political explorations. “I began seeking [an] organization which would deal with the social and economic inequities and problems I saw in the U.S.,” he told artist Yevgeniy Fiks in a 2007 interview. “I joined the Communist Party USA in 1971 after meeting comrades active in my union.” He was elected to the CPUSA National Board and National Committee and served as the party’s New York district organizer, and was also active in the Working Families Party, Left Labor Forum and Veterans for Peace.

Davis also was an accomplished journalist, whose notable work included vivid reports of labor struggles in Australia and New Zealand. He donated his personal papers to the Tamiment Library at NYU, which houses the CPUSA archives, and was honored for lifetime activism at the People’s World Better World Awards event in 2014.

Davis is remembered for his wry sense of humor, empathy, generosity, kindness and snowy white beard — he regularly graced family and organizational holiday events as Santa Claus.

He was predeceased by his first wife, Joan Feder SEAS’65, and is survived by his second wife, Esther Moroze; daughter, Angela ’92; stepsons, Marc Auerbach and Dan Auerbach; and six siblings. Memorial contributions may be made to People’s World, Veterans for Peace NYC Chapter 34 and/or the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

For six decades, Schachter studied chlamydia-related diseases and the bacteria that cause them, as well as their diagnosis and treatment. Thanks in large part to his work, the chlamydial disease trachoma, an eye infection that until 1990 was one of the world’s leading infectious causes of blindness, is expected to be eliminated as a public health issue by 2030.

Schachter, who closed his laboratory at UC San Francisco last summer, says he came upon the focus of his lifelong work largely by circumstance.

“I hadn’t planned to do research on STDs,” he said in a Class Note sent to CCT last year, “but serendipity always plays a role, and living in San Francisco through the Summer(s) of Love provided plenty of opportunity. Chlamydial infections were relatively new, and this gave us chances to make real contributions to public health.”

Schachter was born on June 1, 1936, in the Bronx and was the first in his family to attend college. A chemistry major, he earned a master’s in physiology from Hunter College in 1960 and a Ph.D. in bacteriology from UC Berkeley in 1965. His first academic job was as an assistant research microbiologist at UC San Francisco, and he stayed there for 55 years.

Studies in Schachter’s laboratory focused on the epidemiology and clinical manifestations of chlamydial infections. Schachter recognized that chlamydia was not just an ocular or sexually transmitted disease, but also a systemic one that caused pneumonia in newborns. As a result, screening pregnant women for chlamydia and treating the infected women has become the standard of care in the United States and many other countries.

His laboratory also produced a proof of concept study showing the effectiveness of community-wide treatment of trachoma with azithromycin. This is now the linchpin of an effort sponsored by the World Health Organization at eliminating the disease.

After closing his research lab, Schachter kept his academic appointment and planned to continue analyzing data and writing up his last few studies. “Looking back, I recall the usual academic frustrations, getting funding and so on, but all in all, it has been a blast,” he said of his career.

Schachter was predeceased by his first wife, Joyce Poynter. He is survived by his second wife, Elisabeth Scheer, also a microbiologist; daughter, Sara ’91, and her husband, Brent Bessire ’91; sons, Marc and Alexander; brother, Norbert ’60; and three grandsons.

Black was a self-trained artist who spent more than 40 years creating elaborate pictorial mythologies steeped in art history and popular culture. “What I do is read and make my pictures,” Black told The New York Times in 2013, when he finally had his first New York gallery show, at 64. Why did he wait so long? Black explained that until then he “just never made the effort to sell” his artwork.

Born on January 6, 1949, on the Caribbean island of Aruba, Black began drawing as a child, encouraged by his parents. Many years later he would say of his artwork, “I’ve always done it since — well, I guess, since I’ve known myself.”

A prodigious early reader — like all Arubans, Black learned English, Dutch, French and Spanish in elementary school — he came to New York City in 1965 for high school. He spent much of his time in museums and small music clubs, listening to artists such as Jimi Hendrix. In 1967, Black was asked by the music magazine Crawdaddy to illustrate its reviews of The Beatles’s Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Are You Experienced. Densely composed but done with fine-grained precision in black and white, the results set a model for his later work.

Black entered the College that year and majored in art history. “At Columbia, a wider world of the arts opened up to me,” he said, although he left school during his senior year and never graduated. He supported himself with myriad jobs, but his life revolved around his art — complex, labor-intensive drawings that were often years in the making.

Black’s gallery debut, at Francis Naumann Fine Art in Manhattan, was titled “Insider Art” and consisted of collage-like pencil drawings of historically diverse figures and scenes brought together under umbrella themes. The work was so detailed that the gallery provided magnifying glasses to view it and a multipage guide, with numbered charts of the compositions and annotations by the artist identifying the figures depicted.

Most of the artwork at what turned out to be Black’s only gallery showing was sold, earning him more money than he had ever had. But money was never the point for Black; he was content to labor in solitude in his small apartment in Clinton Hill. “People who become what are called ‘artists’ don’t stop,” he told the Times. “There’s a saying: ‘Everybody writes poems at 15; real poets write them at 50.’”

Black is survived by a nephew, Jean Murphy.

Simon, who was an educator at Harvard for 45 years, had a gift for making complex material appeal to students with little background in his specialty; under his instruction, the term “medieval” became exciting rather than stale. The Victor S. Thomas Professor of Germanic Languages and Literatures, Emeritus, taught from 1964 to 2009 and was renowned for enlivening his courses with slides and humor.

Despite a modest demeanor, Simon was a brilliant speaker and a distinguished scholar who published six books and numerous essays and did extensive work identifying medieval manuscripts at Houghton Library, Harvard’s primary repository for rare books and manuscripts.

Simon entered Columbia as a recent immigrant from East Germany with a far better command of German and Russian than English, yet was awarded Phi Beta Kappa in his junior year. He earned an M.A. and a Ph.D. from Harvard before joining the German department, where his special interests were medieval European literature (1100-1250).

Simon’s teaching of both undergraduate and graduate students focused on two fields: the German medieval court and its literature, and the emergence of theater and performance in medieval German settings. All graduate students in Germanic languages and literatures took his introduction to Middle High German literature, where he insisted that they familiarize themselves with at least 200 poems, among other texts, such as the courtly epics. Later, he also offered a course on the history of the German language, taught by studying texts from different time periods.

Graduate students often gained their first experiences of teaching the Middle Ages as assistants in one of his courses.

Simon was devoted to medieval scholarship, as revealed by his painstaking work in German archives and libraries. In support of his scholarly research, he received awards from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Fulbright Foundation.

His books included Neidhart von Reuental (1975), The Theatre of Medieval Europe (1991) and Die Anfänge des weltlichen deutschen Schauspiels, 1370–1530: Untersuchung und Dokumentation (2003).

Simon is survived by his wife, Eileen BC’58; sons, Anders, Matthew and Frederick; and sisters, Hannelore Rogers and Gundula Lee. Memorial contributions may be made to research on aphasic language disorders, which afflicted Simon following a medical procedure in 2014.

Goodstein devoted his professional life to psychoanalysis, the system of psychological theories and therapeutic techniques related to the study of the unconscious mind that together form a method of treatment for mental disorders.

Goodstein grew up in Manhattan and graduated from Stuyvesant H.S. After earning a degree from the University of Pittsburgh Medical School, he served as a captain in the Air Force and then became an adult and child psychoanalyst in Tenafly. He also was a clinical professor on the faculty of NYU Medical School, teaching as part of the Psychoanalytic Association of New York.

Goodstein was a devoted family man with enthusiasm about the world, an ability to make everyone laugh, a flair for the dramatic and a never-ending intellectual curiosity evidenced by encyclopedic knowledge, attentive listening and incisive questions. He was devoted to improving the lives of family, friends, patients and students. He loved a good joke, a good argument, a good parking spot, art, music, travel, photography, the New York Yankees, bear hugs and dark chocolate.

He is survived by his wife of 58 years, Carolyn (née Ehrlich); son, Clifford; daughter, Catherine, and her husband, Ian Wallace; and two grandchildren.

For many people, their college years can shape their lives. Such was the case for O’Connor, who was born August 17, 1941, in Chicopee, Mass., the oldest of 10 children.

O’Connor was a popular running back on the fabled 1961 football team that won Columbia’s only Ivy League Championship. A three-year letter winner, he rushed for 860 yards in his career, including 418 in 1961, when he ran for four touchdowns including a 46-yard run against Princeton that remains the longest scoring run against the Tigers in Columbia history. He was captain of the squad the following year, when he was the team’s leading rusher with 250 yards, and was inducted with the 1961 team into the Columbia University Athletics Hall of Fame in 2010.

O’Connor also served in NROTC and entered the Navy after graduation, becoming a nuclear submarine officer serving on the U.S.S. Von Steuben. As a young lieutenant he went to Britain, where he worked for the commander and chief of the U.S. Naval Forces Europe. It was there he met his wife, Terrie (née Grace); they married 10 months later and spent several years together in London.

O’Connor returned to the States and attended the Tuck School at Dartmouth, where he earned an M.B.A., and settled in Saddle River, N.J. He was the director of administration at McCarter & English, a law firm in Newark, N.J., for 25 years. Following retirement, O’Connor worked with his wife at Terrie O’Connor Realtors in Ramsey, N.J.

“Tom was a good friend and a regular attendee of our Class of ’63 lunches over the years,” recalled Paul Neshamkin ’63. “He was a great guy and one of the most popular members of our class.” Added Tom Vasell ’62, “It was a privilege to know Tom for more than 50 years, as a Columbia student, a teammate on the 1961 championship team and a good friend. He was tough, strong and reliable as the day is long. We will miss him dearly.”

O’Connor is survived by his wife; daughter, Katy Smiechowski and her husband, Greg; daughter Nellie Khattab and her husband, Samer; son Matt and his wife, Emma; son Joe and his wife, Katie Cavanaugh; foster sons, Hai Le and Ha Le; and 10 grandchildren. Memorial contributions may be made to The Grace Foundation of Terrie O’Connor Real Estate Companies, 300G Lake St., Ramsey, NJ 07446.

Sorel was born for a life in music. At a time when other children dreamed of being astronauts or athletes, Sorel would run around the house saying, “I’m Chopin! I’m Chopin!”

His parents got him an upright piano and he took to it immediately, so much so that his first teacher, Judy Thomas, recognized Sorel’s potential and suggested he attend the Preparatory Division at the renowned Juilliard School. There, his instructor, Robert Harris, urged the family to buy a grand piano so Sorel could fully develop his talent. His parents responded by purchasing a Steinway, and by 14 Sorel was an accomplished pianist who was substituting for organist George Bryant at St. Ann’s Church and teaching piano lessons to neighborhood children.

Sorel earned a master’s in music education from Teachers College. He was immediately hired by Collegiate School, a private school for boys on the Upper West Side where he had done his student teaching, launching a 38-year career that enriched the lives of generations of young men. In announcing Sorel’s passing on social media, Collegiate said, “He graced our community for 38 years with his passion for music, creativity, deep understanding of the liberal arts and absolute belief in the importance of art being a central part of such an education. His vision for music at Collegiate served to bring meaning into the lives of boys since he first arrived at the School in 1982.”

One of Sorel’s students, Michael Gruters, wrote that his 12 years at Collegiate “would have been nearly impossible without the balance of pure life and humanity that he brought, taught and inspired there. I, along with my friends, remember Mr. Sorel with adoration, a patient musician, filled by music and levity. Don was that magic, loving force that washed over his students and people that knew him. I count myself lucky to be among them.”

Sorel founded and developed the Collegiate Conservatory Program, the school’s K–12 music program, and directed choral groups for 38 years. He played the organ in West End Collegiate Church and worked with Collegiate faculty and students to create their annual holiday program. In addition, Sorel was the organist at The Brick Church in New Hempstead, at St. Francis of Assisi Church in West Nyack and, for the last 30 years, at St. Margaret Church in Pearl River, where he teamed with his high school sweetheart and wife, Terri (née Slaker), who was the music director and cantor.

Sorel’s wife survives him, as do his sons, Jason, Jeffrey and Alex; sister, Michele, and her husband, Darryl G. Ivey; brother, Patrick, and his wife, Leslie; and numerous cousins, aunts and uncles.

Dr. Robert H. Weitzman ’62

Retired physician who lived in Linden, N.J., died on April 7, 2020.

Weitzman dedicated himself to helping others, whether as a cardiovascular and pulmonary specialist at hospitals in Central New Jersey, while seeing patients in his private medical practice or as a lay leader at his local synagogue, Congregation Anshe Chesed.

“He was a member of the board of directors and a very generous supporter,” said Rabbi Joshua Hess of Anshe Chesed. “I found him to be extremely insightful. He would present his ideas in a way so that people would listen to him. His advice was valued and often taken. He came to services every Saturday and was a part of the Anshe Chesed family.”

A graduate of Linden H.S., Weitzman earned an M.D. in 1966 at NJCM, and served his internship at Beth Israel Hospital in New York and his residency at Orange County Hospital in California. During the Vietnam War, he was stationed in Danang on staff at the U.S. Naval Hospital.

Once back home, Weitzman became an attending physician at the Hackensack Meridian Health JFK University Medical Center in Edison, N.J. The cardiovascular and pulmonary-disease specialist became chief of pulmonary medicine at Muhlenberg Regional Medical Center in Plainfield, N.J., a teaching facility with a nursing school and medical residency program that merged with JFK Medical Center in 2008. He also ran a clinic in Westfield, N.J., and was an associate professor at New Jersey College of Medicine.

Weitzman was a lifetime member of Congregation Anshe Chesed and a donor to many Jewish causes. He is survived by his brother, Morton ’55, sister-in-law, Laura; niece, Robin; nephew, Howard; and a great-nephew. Memorial contributions may be made to Congregation Anshe Chesed, 1000 Orchard Terr., Linden, NJ 07036.

Steiner was a leader in the study of the philosophy of mathematics, a groundbreaking author, and a tireless teacher and scholar. Until the week before his death, he was teaching a popular seminar on the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, where he chaired the philosophy department.

Born in the Bronx, Steiner entered Columbia in 1960 but spent 1963–64 with Mel Barenholtz ’65, GSAS’73 studying Talmud at Yeshivat Kerem B’Yavneh in Israel. Barenholtz recalled, “In a yeshiva, students attend a daily lecture in Talmud and, for the rest of a 10-hour day of study, they study in pairs. For the entire school year, for about six hours each day, Mark and I studied Talmud and Codes together. We had a great year and always cherished the experience.”

Steiner returned to the College and completed his degree in philosophy. Azriel Genack ’64 recalled Steiner as being “deeply engaged with fellow students and faculty, especially with Professor Sidney Morgenbesser,” with whom he developed a close friendship that lasted more than 40 years.

After a Fulbright Fellowship at Oxford University, Steiner earned a doctorate from Princeton in 1972 before becoming an instructor at Columbia. He moved to Israel in 1977 and became the chair of the philosophy department at Hebrew University in the 1990s, although he often returned to Columbia to teach during the summer.

The overlap between Steiner’s Jewish commitments and his academic interests was evident in his tendency to use rabbinic anecdotes to illustrate his points while debating with his colleagues. His religious inclination also led to a series of studies, including a research project in which he drew parallels between medieval Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides and 18th-century Scottish thinker David Hume. Steiner also translated a series of previously unknown Jewish philosophy books from Yiddish to English.

In his most famous book, The Applicability of Mathematics as a Philosophical Problem (2002), Steiner argued that man’s ability to discover natural laws means that the universe is innately user friendly and that there is meaning and reason in things. He also published on Jewish philosophy, including articles on the philosophy of Rabbi Israel Salanter and Saul Kripke, and especially on Rabbi Reuven Agushewitz, whose work he rescued from obscurity and translated into English.

Steiner is survived by his wife of 54 years, Rachel Freeman BC’65; brother, Richard; sons, Hillel, Yoel and Aharon; daughters, Hadas and Navah; and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

The experience of a lifetime can come at any time. For Dickstein, it was the 1961 college wrestling season, when he helped Columbia to its first Ivy League wrestling championship. The lessons he learned and friendships he formed on the wrestling mat and in the locker room that winter helped shape the rest of his life.

“The group of guys was special,” Dickstein said in an article published by Columbia Athletics in 2011, the 50th anniversary of that championship season. “Each wrestler was a good guy and we really enjoyed each other. There were no jealousies. We were rooting for each other, and all had great senses of humor, which translated into a lot of fun.”

Born on April 16, 1941, in New York City, Dickstein spent his early childhood in Washington Heights before moving to Teaneck, where he lived the rest of his life. After majoring in economics, he went to NYU Law and became a successful real estate attorney in Hackensack, N.J. He retired in 1995 in order to focus on helping people who suffered from addiction, and mentoring countless students in sports, making them not only better athletes but also better human beings.

But his lifelong passion was wrestling. Dickstein was the freshman wrestling coach for the Lions while at law school and was an ardent supporter of the Columbia wrestling program the rest of his life, spending countless hours refereeing and attending matches all over the country.

Shortly after his death, Columbia Athletics established the Bob Dickstein Memorial Award, given annually in his memory to the member wrestling team member “who best embodies Bob’s joy for living and adventure of spirit. It is presented to whoever has made the greatest contribution in terms of inspirational leadership, sportsmanship and college loyalty.” The first recipient of the award, presented on April 13, 2020, was Joe Franzese ’22.

One day Dickstein never forgot was February 25, 1961, when the Lions hosted Cornell, winner of five consecutive Ivy titles, in a matchup of teams that were unbeaten in league competition. “All of the experts on Ivy League wrestling gave us no chance at the beginning of the season,” Dickstein, who wrestled at 157 lbs., recalled 50 years later. “But sometime during the middle of the season, we were gaining confidence and honestly believed we could win.” And win they did, when heavyweight Lou Asack ’63 pinned William Werst to complete a 17–12 victory for the Lions. One week later Columbia defeated Penn to seal the Ivy championships.

Asked his feelings, Dickstein summed it up succinctly: “Ecstasy and euphoria!”

Dickstein is survived by his wife, Janet; brother, Jerry, and his wife, Ivette; daughters, Carol Manso and Holly; and four grandchildren.

Diaz was a contract engineer, mechanical controller, import/export man and vitamin manufacturer before settling into his calling as campus plant manager at Haverford (Pa.) College. He championed causes such as community food co-ops and quality integrated schools in Philadelphia and was passionate about the visual and performing arts, avidly listened to jazz and appeared in numerous community theater productions. According to family, he loved life, was never bored, rarely complained and readily talked with people he encountered, occasionally to the embarrassment of relatives.

Born in New York City and raised in Washington Heights, Diaz earned a B.A. in pre-engineering and B.S. in mechanical engineering. He worked for Standard Oil Pipeline, as a contract engineer for a construction company in Southern California, for a joint venture aerospace simulator construction company and as a mechanical controller at Philadelphia Burner Service. After his parents were killed in a car crash in 1969, he took over his father’s import/export business to Central America and began making vitamin-rich emulsions including Ceregen, Ozomulsion and Nervita. But when shipments were repeatedly hijacked in 1978 in El Salvador during civil unrest, those businesses went on permanent hiatus.

Diaz became the manager of Day & Frick, a Philadelphia manufacturer of vitamins and supplements, but landed his dream job in 1986 when he became physical plant director at Haverford, supervising construction and renovations on campus until retiring in 2009. He loved the college community, arts and culture, and in retirement enrolled in classes at West Chester University to earn a teaching certificate in secondary mathematics.

Blessed with a resonating stage voice and a dashing physical presence, Diaz enjoyed participating in productions at Stagecrafters Theater and Allens Lane Art Center, both in Philadelphia, including Don Juan in Hell; Curse of the Starving Class; Sticks and Bones; A Runner Stumbles; A Doll’s House; Catch-22; Little Murders; and Little Alice. He was an advocate and supporter of Philadelphia arts such as the Fringe Festival, International House films, PlayPenn, Pig Iron, the Institute of Contemporary Art and many others. He also loved jazz, so much so that he regaled family with stories of having seen Miles Davis weekly while in NYC, and listened to jazz on the radio as he went to sleep.

Diaz is survived by his wife, Pamela Kerr; son, Austin; daughters Lisa Riegel, Cymantha Liakos and Christina Diaz Meyer; and nine grandchildren. Memorial contributions may be made to your favorite community arts organization or the Temple University Lung Center.

Steiner could easily be identified by his New York Yankees baseball cap, which he proudly wore for many years to and from work, between his home in the Briarwood neighborhood of Queens and his office in lower Manhattan.

Born in the Bronx, Steiner majored in history and earned a master’s in American history from GSAS. He was very active at Spectator; he covered sports for four years and was sports editor in his senior year. He also was known as a trivia expert, particularly on baseball and especially on his beloved Yankees.

Early in his professional career Steiner taught history and Spanish at a high school in Brooklyn and later was a sports writer. In 1994 he became director of public relations for the American Jewish Congress and associate PR director for the Council of Jewish Federations, serving in both positions for eight years. In 2002 he became director of public relations for the Orthodox Union (OU), a position he held for more than a decade until his retirement.

To his colleagues, Steiner was the kind and friendly man who arrived at the office wearing a Yankees cap and toting a doorstop of a book about American history. “He was always reading these really huge books all the time,” recalled Rabbi Menachem Genack, the head of the OU’s kosher division. “He was just the nicest person. I really miss him.”

Tova Cohen, who worked for Steiner at the OU, said, “One morning at work, I received a phone call from someone about an auction I had entered, telling me I won a free trip to Israel. I was so excited I shrieked with joy in middle of the entire office. Steve came running over to see what was going on; when I shared the news, he was so genuinely thrilled for me and immediately started strategizing about when I could take this vacation. That’s always what struck me the most about Steve — he truly shared in other people’s joy in a rare and beautiful way.”

Steiner is survived by his wife, Joy; son, David Jason; and daughter, Andrea.

McNally’s work introduced theater audiences to homosexual characters and situations that most mainstream productions had shunted into comic asides. In a conversation with Philip Galanes in The New York Times Style Magazine in 2019, Galanes noted, “You were a pioneer, one of the first playwrights to explore gay characters in your work — from the very beginning, in the 1960s. Did you see that as bravery?” to which McNally replied, “Not at all. I saw it as: These are people. I wasn’t writing these plays in Texas. I was writing them in New York, which is sophisticated. I always felt it was O.K. to be gay in the American theater.”

McNally was a remarkably prolific dramatist, with some three dozen plays to his credit, as well as the books for 10 musicals, the librettos for four operas and a handful of screenplays for film and television. He won Tony Awards for the musicals Kiss of the Spider Woman (1993) and Ragtime (1998), and the plays Love! Valour! Compassion! (1995) and Master Class (1996), and was presented the 2019 Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement.

In 2018 McNally was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He was presented the 2015 Lucille Lortel Lifetime Achievement Award and the 2011 Dramatists Guild Lifetime Achievement Award. McNally was inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame in 1996.

The College presented McNally with a 1992 John Jay Award for distinguished professional achievement, and in 2004 he was presented with Columbia’s inaugural I.A.L. Diamond [’41] Award for Achievement in the Arts. He was the 2013 Class Day speaker.

McNally is survived by his husband of 17 years, Thomas Kirdahy, and a brother, Peter.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu