Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Why Home Ec Deserves Respect

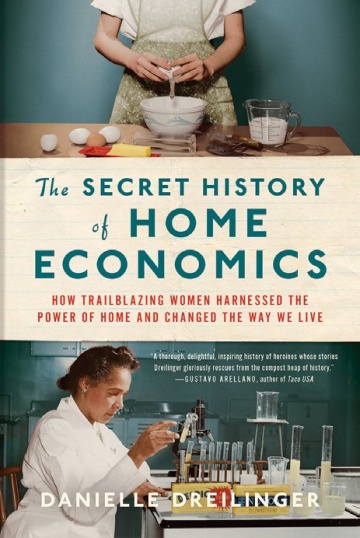

Most people don’t think of science, feminism or cultural influence, but Danielle Dreilinger ’99 is determined to change that. In her debut book, The Secret History of Home Economics: How Trailblazing Women Harnessed the Power of the Home and Changed the Way We Live (W.W. Norton & Co., $27.95), Dreilinger engagingly tells the stories of the field’s founders and describes the creation of a home economics movement that instructed and inspired generations of women. She also shines a light on the racism that existed within the movement and the strides made by women of color who were influential leaders and innovators; highlights what the field brought to the 20th century (hello, seven food groups, school lunches, clothing-care labels); and makes a solid case for home economics as a necessary source of study today.

In the 19th century, home economics education was an avenue for women to enter the sciences; one of the field’s founders was a chemist, Ellen Swallow Richards, who was the first woman to graduate from MIT (the book includes an amazing photo from 1890 of a petite Richards holding space among 25 heavily mustachioed colleagues). From the beginning, the movement’s intent was to change the world through the household, and to help people live better lives. “In 1899 home economists argued for school gardens, STEM education for girls, takeout food, and affordable day care,” Dreilinger writes. “And yet home economics has been denigrated over and over again as ‘just stitching and stirring.’”

By compellingly spotlighting the heroines of the movement and outlining the practical benefits offered by modern home ec curriculums, Dreilinger makes the case for a comeback. “Home economics is, can, and should be an interdisciplinary, ecological field that explores the connections between our homes and the world,” she writes.

Danielle Dreilinger ’99

KATHLEEN FLYNN

Dreilinger spent three years doing intense research, which she says was an enormous pleasure (fun fact: she found a number of helpful documents in the Butler Library archives); it’s the kind of work she’s enjoyed since her time at the College. “What I loved about Columbia was finding a place where I could talk about books and problems,” she says. “The more I’ve been able to do that since, the happier I’ve been. And the research and reporting for this book was tons of books and tons of problems.”

It was also at the College that she learned how to cook for herself. “I didn’t have a meal plan after my first year, and my dorm was a converted apartment building with a kitchen,” Dreilinger says. “So I got an early start on that practical matter. And that’s really what home ec is — it’s not Gourmet magazine; it’s about basic cooking and how to feed yourself, and also about culinary career preparation and learning how our food systems work.”

Dreilinger is hoping her book will help to kickstart a national dialogue about bringing home economics back into visibility and relevance; she’d love to see the teaching of practical life skills become mandatory for middle- and high-schoolers. “As an education reporter, I know what a tall order it is to tell states to make something mandatory, but I also think that’s how you bump something up the priority list,” she says. (She urges interested parents to speak out at their local Board of Education meetings. “I’ve covered I don’t know how many state and school board meetings, and they really do matter,” she says.)

This a promising moment, Dreilinger says, because we are thinking more about home economics than we have in a long time. The last two decades have seen dramatic growth in homemaking media — thousands of DIY and cooking blogs, Real Simple, the Food Network, Project Runway, Michelle Obama’s health and fitness initiatives, and more. We’ve also spent an inordinate amount of time in our homes recently because of the Covid-19 pandemic: “People are more aware than ever about the permeability of those four walls; the home may be a refuge, but it is also political and economic,” Dreilinger writes. “We are recognizing the importance and the inescapability of the work that takes place inside the home.”

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu