American Library Association president Emily Drabinski ’97 is fighting for the right to read.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

American Library Association president Emily Drabinski ’97 is fighting for the right to read.

Drabinski has strong connections with library leaders at Columbia. “I’m grateful for Emily’s courageous leadership and persistent vocal support for library workers whose brave efforts uphold the essential value of intellectual freedom,” said Ann Thornton, vice provost and University librarian. “We must strengthen our resolve to ensure that libraries are for everyone.”

Photographs by Jörg Meyer

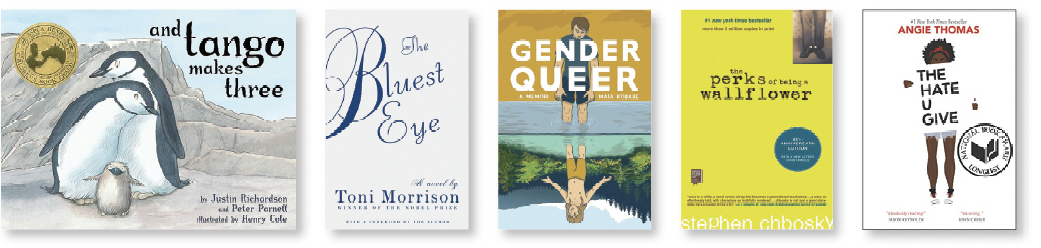

The national media has made it hard to miss the measures being taken by conservative groups like Moms for Liberty and politicians like Florida’s governor Ron DeSantis to remove books from school libraries. In February, a Pensacola school board voted to ban a children’s book about two male penguins raising a chick; last fall, The Bluest Eye, by Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, was pulled from shelves in a school district outside Dallas-Fort Worth.

American Library Association (ALA) president Emily Drabinski ’97 is on the front lines in this increasingly contentious battle for the right to read. “Libraries didn’t choose to be the terrain of struggle, but here we are,” she says.

There is reason for concern — instances of book bans are multiplying, and they’re not just happening in schools. The number of attempts to remove or restrict books doubled in 2021 and nearly doubled again in 2022, according to the ALA. Its Office for Intellectual Freedom documented 1,269 demands to censor public and school library books and resources last year, the highest number of challenges since the ALA began compiling data in 2001. Forty-eight percent of those targeted materials in public libraries.

A record 2,572 unique titles have come under fire, most by and about LGBTQ and BIPOC authors and experiences; a snapshot of challenged books includes Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe (LGBTQ content, claimed to be sexually explicit); The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky (depiction of sexual abuse, LGBTQ content, drug use); and The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas (profanity, violence, thought to promote an anti-police message and indoctrination of a social agenda).

Drabinski assumed the leadership role on July 1, serving a one-year term during a critical moment in the history of American libraries. “Public libraries have only a teeny fraction of most city budgets, which makes them very vulnerable,” says Drabinski, an associate professor at Queens College Graduate School of Library and Information Studies. “Library workers need support — they need media training and advocacy training to talk about what’s happening. And we have to make sure the public sees that the library is an anchor institution in their communities.”

She is the first publicly gay ALA president, which is relevant at a time when LGBTQ life is under attack. Of the 13 titles on the ALA-compiled “Most Challenged Books of 2022” list, seven (including three of the top four) were singled out for having LGBTQ content. Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, said the list “sends a message to the LGBTQ community as a whole that they’re not considered full citizens with full rights to participate in community institutions like the library.”

Significantly, Drabinski campaigned on a pro-labor platform that emphasized the importance of organizing library workers. “I come out of unions, and that’s shaped my theory of change,” she says. “If we want to win, we need mass movements and density — I think a densely unionized sector is crucial to the survival of libraries. Because the people who are fighting back against book banning every day are the people who work at the library. The project for me is to help more library workers understand and build their own power, which we can exercise collectively for the world that we want.”

“Emily is a strong and passionate advocate for library workers, libraries and the ALA,” says Lessa Kanani‘opua Pelayo-Lozada, ALA president from 2022 to 2023. “She lives her values and I am excited to see how she continues leading the ALA, bringing a focus to library worker rights in addition to fighting for intellectual freedom and communities.”

The number of demands to censor library books (such as And Tango Makes Three) peaked in 2022, according to the American Library Association.

The ALA reports that prior to 2020, the vast majority of banning attempts were made by individuals who sought to restrict access to a single book their child was reading. But the group found that 90 percent of recent challenges were directed at multiple books, and nearly 20 percent were made by political or religious groups. The ALA considers the sharp increase in book bans as evidence of an attack “by a growing, well-organized, conservative political movement, the goals of which include removing books about race, history, gender identity, sexuality and reproductive health from America’s public and school libraries that do not meet their approval.”

Drabinski chuckles when she says she is “popular” with the right-wing media. After she was elected in April 2022, Drabinski tweeted that she couldn’t believe “a Marxist lesbian” would be the next president of the ALA. It got around. (The tweet has since auto-deleted; Drabinski doesn’t keep messages longer than 30 days.) Two weeks into her presidency, the Montana State Library Commission voted to leave the ALA because of her comment.

“It’s been a wild ride,” Drabinski says. “I mean, I knew there would be some backlash about me. But we’re just going to keep going. Libraries are in the crosshairs right now in ways I never could have anticipated. We need leadership that’s loud, that can make people see that the ALA is a leader on these issues that are coming at everybody.”

Drabinski references kairos, the ancient Greek word for time; specifically, an opportune time to do a particular thing. “This is a Kairotic moment, which requires a certain kind of action,” she says. “I’m loud — I’m really loud. So I’m hoping to just be really fucking loud for a year.”

Drabinski is from Boise; she never learned to drive, so she applied to colleges in cities with good public transportation. She was a recipient of the Gideon Oppenheimer [’47, LAW’49] Scholarship Trust, for students from Idaho; coincidentally, her identical twin, Kate Drabinski BC’97, also landed at Columbia.

Though she majored in political science, Drabinski dreamed of becoming a writer (she credits Logic & Rhetoric for honing her skills). After graduation, she became a fact checker at Lucky, the now-defunct shopping magazine. “I was in the doghouse for a week because I listed the wrong phone number for a department store; I thought, ‘I can’t live my life this way,’” Drabinski says.

Drabinski’s first library job was organizing the card catalogs in Butler.

Drabinski was coordinator of library instruction at LIU for seven years before becoming a critical pedagogy librarian at CUNY’s Graduate Center in 2019. “Critical pedagogy is about teaching students how to determine what types of knowledge and information are worth engaging with, while teaching them to use them well enough to pass their classes. That’s what librarians do — we teach people how to use systems.”

She is understandably passionate about the role libraries play in society. “Librarians select and acquire knowledge on behalf of our communities, and we facilitate equitable access to those resources,” Drabinski says. “It’s a big job. And I think it’s really important.”

No doubt most people would agree; pre-internet, the local public library was often the only game in town for research and reading material. Libraries still provide that vital service, along with access to computers, bathrooms, a drink of water and children’s story hours (“Imagine if you had to buy every single picture book that you wanted your kid to read!” Drabinski exclaims). And so it’s distressing that these generally benevolent spaces have become subject to witch hunts and harassment. In Drabinski’s home state, legislators passed a bill that would allow anyone in the community to sue a librarian for $2,500 if they felt the librarian had circulated inappropriate materials (Idaho’s governor vetoed the bill; an attempt to overturn the veto failed by a single vote).

“I’m an Idahoan through and through,” Drabinski says. “People there deserve to read; they deserve to be able to go into the library and see some book about themselves. Everybody does.”

The good news is, the majority of Americans aren’t down for this. The ALA reports that 71 percent of voters oppose efforts to have books removed from their local public libraries, including a majority of Democrats (75 percent), Republicans (70 percent) and Independents (58 percent). President Barack Obama ’83 recently lent his support, sending an open letter to the ALA in July that condemns “profoundly misguided” right-wing efforts to ban books in public school libraries.

This year’s Banned Books Week, the ALA’s celebration of the freedom to read, is October 1–7. The annual event draws attention to current and historical attempts at censorship in libraries and schools, and brings the entire book community — librarians, booksellers, publishers, journalists, teachers and readers of all kinds — together in solidarity.

Still, the battle rages on. Drabinski has spent much of the past year traveling around the country, talking to librarians about their challenges and promoting the great work they’re doing. She recently returned from Marion, Iowa, where she met a librarian who had started his job just three days before a deadly derecho hit the state.

“The town was completely flattened, and this guy steps in and sets up a computer lab in the park, running off a generator, to help people connect to their insurance plans and get other information they needed,” Drabinski says. “I’m trying to gather as many of these stories as I can so that people understand the roles that libraries play in their own communities.” At the end of her term next June, she hopes to drive a pro-library tour bus from Rhode Island to the ALA Annual Conference in San Diego.

Drabinski expects the book banning issue will intensify in the run-up to next year’s presidential election, and she says she is more than ready for the fight. “The right really wants to attack libraries for their so-called ‘corrupting influences,’ and they’re trying to make libraries about me, specifically,” she says. “The right-wing press thinks I’m terrible, they’ve attacked me for being queer — but I’m not the first and I won’t be the last. I’ve been pilloried in public from my time in unions. I’ve had cancer.” Drabinski shakes her head.

“They’re not going to kill me. I’m really kind of bulletproof.”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu