Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

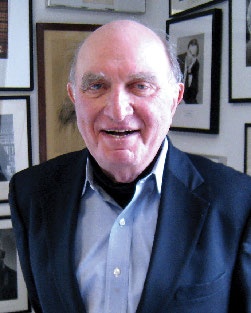

Norman Dorsen ’50, Civil Rights Advocate

Norman Dorsen ’50, a passionate human rights advocate who led the American Civil Liberties Union for 15 years and was involved in some of the biggest civil liberties cases of the 20th century, died on July 1, 2017, at his home in New York City. He was 86.

THOMAS F. FERGUSON ’74

Dorsen’s career-long focus on civil liberties was informed by his involvement in the Army-McCarthy Hearings, in 1954, which concerned claims by Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy and his chief counsel, Roy Cohn ’46, LAW ’47, that Communists had infiltrated the federal government and the Army. In addition, Dorsen argued Supreme Court cases that established juveniles’ rights to due process and that acknowledged the rights of children born out of wedlock. He was also one of the first attorneys to argue before the court in favor of abortion rights and gay rights.

Born on September 4, 1930, in New York City, Dorsen was a stellar student and attended Bronx Science, then entered the College at 16 while still living at home. By 23 he had finished Harvard Law School, where he had been an editor on the law review. He later studied international economics as a Fulbright scholar at the London School of Economics and clerked for Justice John Marshall Harlan II on the Supreme Court, where he was remembered by Justice William J. Brennan Jr. as principled and “indefatigably persistent.”

After Harvard, Dorsen became a lieutenant in the Army and went up against McCarthy and Cohn. “There is no doubt that being confronted by the McCarthy crowd, and in particular by Roy Cohn, sensitized me to issues of fairness in hearings and other proceedings and the drastic harm that the government can do to free expression,” he told CCT for a Spring 2013 profile.

A key figure at NYU School of Law, where he joined the faculty and became the director of the civil liberties program in 1961, Dorsen’s influence was partially responsible for the school’s reputation for attracting students and faculty with an interest in public interest law.

In a 1992 tribute, Brennan recalled a case that Dorsen had felt particularly strongly about. “For weeks before and after the case was argued, he pursued my law clerk relentlessly through the halls of the court, peppering him with arguments,” Brennan wrote. “Sooner or later, Norm calculated, my clerk would agree, exert his influence and induce me to see reason.”

Dorsen demonstrated that perseverance before the court many times as a litigator. In 1967, he helped convince the court that Arizona had acted unconstitutionally after sentencing a 15-year-old to six years in prison for making an obscene phone call. In 1968, he successfully argued that Louisiana could not discriminate against children born out of wedlock.

As general counsel of the ACLU, a role he took on in 1969, becoming president in 1976, Dorsen helped guide the organization through many challenges, including its defense of the rights of Nazis to stage a march through Skokie, Ill., in 1977. The following year, The New York Times credited Dorsen with “a magic touch for healing organizational wounds.” He also helped build The Arthur Garfield Hays Civil Liberties Program at NYU Law into a powerhouse. In 1995, he became the founding director of the Hauser Global Law School Program at NYU, one of the first programs of its kind.

In 2000, President Clinton awarded Dorsen the Eleanor Roosevelt Human Rights Award. In a statement introducing the award winners, the White House referred to Dorsen as “a tenacious and outspoken defender of human rights.”

Dorsen was predeceased by his wife of 46 years, the former Harriette Koffler, in 2011. He is survived by his daughters, Annie, Jennifer and Caroline; brother, David; and four grandchildren.

— Lisa Palladino

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu