After a turn as Aaron Burr — and a moment in the hot seat — Brandon Victor Dixon ’03 continues to dazzle on and off Broadway.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

After a turn as Aaron Burr — and a moment in the hot seat — Brandon Victor Dixon ’03 continues to dazzle on and off Broadway.

I

Brandon Victor Dixon ’03 backstage at the Signature Theater before rehearsals for F**king A.

JÖRG MEYER

The veteran actor was sitting in his usual booth at E&E Grill on West 49th Street when he learned that he would be delivering a message to Vice President-elect Mike Pence after that night’s performance of Hamilton. It had been almost four months since Dixon replaced Leslie Odom Jr. as Aaron Burr in the megahit Broadway show about our Founding Fathers. It was only eight days after the election that inflamed an already divided country. And it was 15 hours before the President-elect would start tweeting about the speech that threw Dixon under his hottest spotlight yet.

The way Dixon tells it now, in between bites of fish tacos in the lobby of the Intercontinental New York Times Square, he wasn’t nervous about addressing Pence: “He’s just a man, and I mean, I knew something of what kind of person he was at that point. Individuals like that are not going to intimidate me.”

At curtain call, Dixon’s instinct — honed from 12 years on Broadway — told him that security would usher Pence out of the theater immediately after the show, so he stopped the cast’s bows to make sure Pence heard him. “That bright, silvery spot of hair started to move with all those dark suits around him and I was like, ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa,’” Dixon recalls.

The two-time Tony nominee began to improvise: “Vice President-elect Pence, I see you walking out, but I hope you will hear us just a few more moments,” he said, before reacting to the chorus of boos emanating from the audience. “There’s nothing to boo here, ladies and gentlemen, nothing to boo here. We’re all sharing a story of love.”

Pence stopped to listen, and with the audience at attention, Dixon took out a note written by the show’s creator, Lin-Manuel Miranda, in collaboration with its producers, cast and crew. Dixon welcomed and thanked Pence for attending before continuing: “We are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious your new administration will not protect us, our planet, our children, our parents, or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights. But we really hope this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and to work on behalf of all of us. All of us.”

The Atlantic later described it as “one of the most publicized peaceful protests in theatrical history.”

Dixon’s infamous speech to VP-elect Mike Pence put him in the national spotlight and onto the cover of Variety’s January 2017 “Inauguration Issue.”

COURTESY VARIETY

Without getting out of bed, Dixon responded with the first thing that came to mind: “conversation is not harassment sir. And I appreciate @mike_pence for stopping to listen.”

Dixon will never know for sure why the show’s executive team selected him to give the speech. Maybe it was because his decade-plus stage experience made him the unofficial leader of the cast. Or because, as an activist for civil rights issues, he would bring a deeper meaning to the words. Perhaps it was because he speaks, even in normal conversation, as though he’s reciting long, eloquent prose. Or maybe it’s because he is cool, collected and gracious — enough to prop an iPhone recorder on his shoulder during an hour-long interview after the waiter declined to lower the hotel’s blaring pop hits.

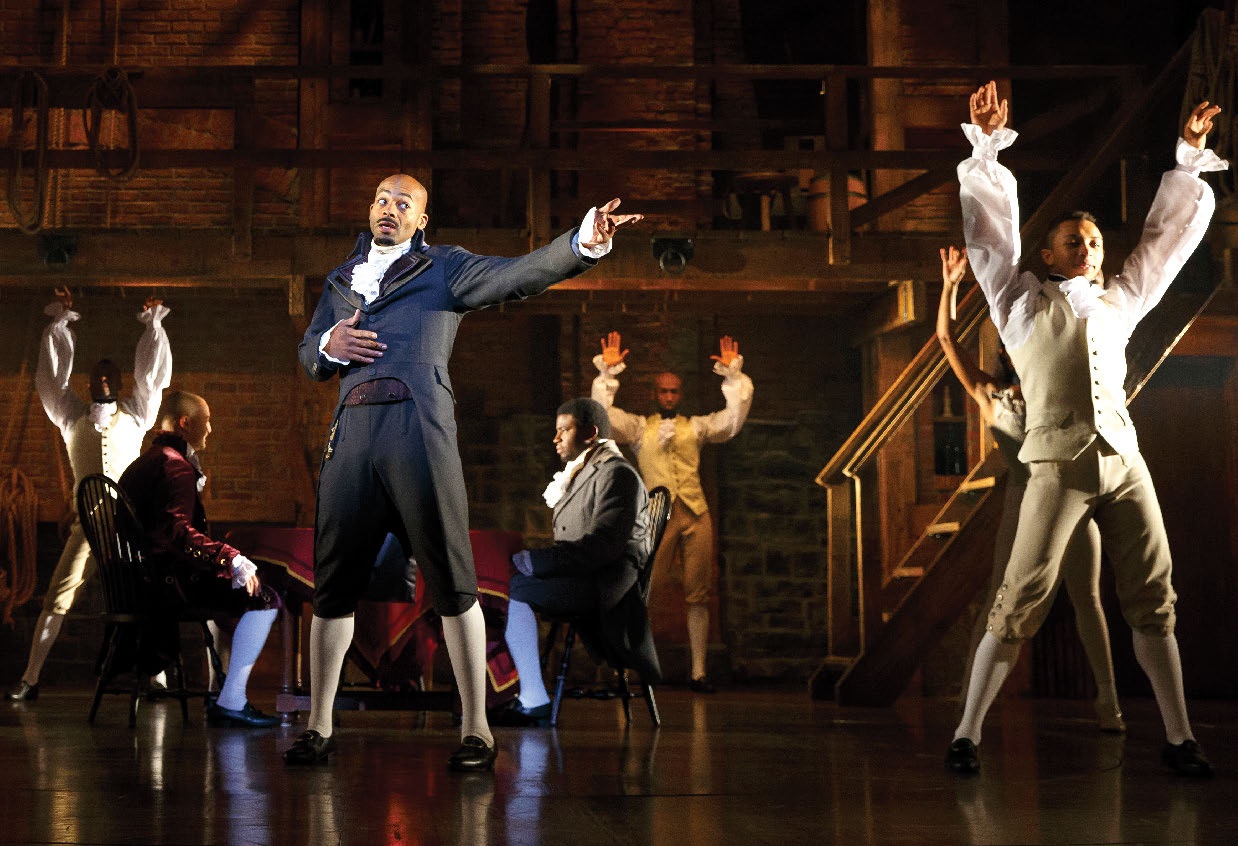

Not the same old song and dance: Dixon as Aaron Burr in Hamilton.

Whatever the reason, Dixon denies his newfound prominence (a Variety cover notwithstanding). “I’m only famous in Midtown,” he jokes. And maybe he’s right. The tourists sitting across from us seem unfazed. His shaved head, perfectly arched brows and eyes that narrow when he kids — which is often — are not yet recognizable.

But those in his orbit would beg to differ. “People are stopping him in the street all the time. It’s terrible walking four blocks with him now,” says Warren Adams, his friend and production partner. “He gets stopped and it’s ‘Thank you’ and ‘Thanks for speaking up for all of us.’”

As a child, Dixon knew he belonged onstage: “It’s the same way I knew I had two hands and two feet.” The Gaithersburg, Md., native won a scholarship to study at the British American Drama Academy in Oxford for his junior year of high school, and by senior year he’d been selected as a U.S. Presidential Scholar semifinalist.

He nabbed the lead role of Simba in the traveling tour of The Lion King at 21 and left Columbia his senior year. Not throwing away his shot paid off. The series of roles that followed cemented him as a star. His Harpo in The Color Purple earned him a 2006 Tony nomination, and his turn in the Off-Broadway The Scottsboro Boys, in 2010, garnered a slew of nominations including Drama Desk and Drama League Awards. (In 2014 he revisited the role for a production in London’s West End and received an Olivier nomination.)

"People are stopping him in the street all the time.

It’s terrible walking four blocks with him now. He gets stopped

and it’s ‘Thank you’ and ‘Thanks for speaking up for all of us.'"

As a first-generation Jamaican-American — and the first generation on his father’s side to go to college — Dixon made a point to earn his diploma, though. He finished his degree in 2007 and received Columbia’s I.A.L. Diamond Award for Achievement in the Arts the same year.

Hamilton director Thomas Kail remembers Dixon’s original Scottsboro Boys performance as the first time “where I really saw him in a very intimate setting, carry a show and be so fully integrated into an ensemble. That was probably my first full memory of ‘Wow, who is this?’ He was both commanding and compassionate, and he was someone who felt like he belonged on stage in a way that is rare.”

Adams agrees that Dixon seemed destined for the theater. Before the two became production partners, they worked together on Motown (2013), where Dixon played the lead role of legendary music producer Berry Gordy Jr. Adams was impressed from day one: “Brandon’s one of those people who walks in the room and a light goes on.”

“Brandon brought power, heat and passion to his work.

Eight shows a week he managed to be both consistent and surprising.”

Make no mistake: Dixon is also one of the hardest working. “He is probably the most prepared person I have ever worked with,” Adams says. “Getting to rehearsal, specifically the table read, people have their scripts. Brandon walked in off-book. So you’ll have a 130-page script and every day, we’ll make changes and create pages and we’ll give him more, and by evening, he’s off-book of those pages, too.”

Known for his charismatic stage presence and seductive voice — New York magazine has called him “the lost member of Boyz II Men” — Dixon has been singled out in The New York Times for his “star power,” singing with “passionate fervor” and “especially affecting” performances. His second Tony nomination came just last year, for playing ragtime pianist and composer Eubie Blake in Shuffle Along, or, the Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed.

Dixon’s impressive résumé put him on the Hamilton team’s radar in the show’s earliest development. He auditioned years ago for the workshop, but the main roles were already taken. “I got to know him in that context, as someone who got a chance to play in an audition and watched how he made really smart, fully realized choices walking into the room,” says Kail. “From his dedication to the form to his ability to bring humanity to every role. He obviously has a tremendous talent.”

Stepping into Burr’s revolutionary boots last August was an anomaly for Dixon, who originated almost every other role in his career.

“It can mean a lot for someone in this industry to see you in something that is really well written and diverse,” Dixon says. “One of the most extraordinary things about Hamilton, below the surface, is that it’s a brilliant piece of generous work that now provides a lot of individuals of color — who don’t often have a lot of opportunities to do diverse, rich work — the chance to do so, and the chance for people in the industry to see it.”

Consider him seen. The Washington Post’s Alyssa Rosenberg praised the “wonderful humor” he brought to the role, and Deadline’s Jeremy Gerard described Dixon’s “The Room Where It Happens,” as “the show’s most astonishing number.” Bryan Terrell Clark, the show’s current Washington, says: “Brandon brought power, heat and passion to his work. Eight shows a week he managed to be both consistent and surprising.”

Dixon played his Burr as a trickster. “To have risen through the Army ranks so rapidly at a young age, driven his way through Princeton at a young age, and to rise through politics the way he did despite the internal [hatred] toward him means that Burr must have possessed a charm and a candor and an intelligence and a wit that would draw people to him. I used that.”

Now the world’s going to know Dixon’s name. Having left Hamilton in August, Dixon has a recurring role on the Starz drama series Power, a guest starring role on NBC’s Gone with Chris Noth and an album in the works. He’s also finishing up an Off-Broadway run in the play F**king A, a modern retelling of The Scarlet Letter, in which Hester is on a quest to find her jailed son, played by Dixon.

Dixon as attorney Terry Silver on Power, with co-star Naturi Naughton.

COURTESY OF STARZ ENTERTAINMENT LLC

At 36, Dixon is confident in his ability to interpret any character — no matter how beloved or Tony Award-winning. In fact, looking back, Dixon says playing Burr was “one of the easier problems that I’ve ever had.” He does not mean to brag. Everything is relative, and the only reason for this current confidence, he says, is an existential crossroads he faced a few years earlier in his career. As he describes it (in dramatic fashion, he admits), he had a crisis of faith in 2014, found his way back in 2015 and was resurrected in 2016.

The New York Times said Dixon was “memorably” cast in F**king A; here, with Elizabeth Stanley.

JOAN MARCUS

Dixon began internalizing the magnitude of the job in front of him, hyperconscious of the greatness he had to both represent and manifest. “Berry Gordy, Doug Morris, the [co-producer and] head of Sony Music. These are the people who can change my life in a moment,” Dixon recalls of his mindset. By the end of the process, if I’m not a star, it’s because I’m not good enough. Because these people are star-makers.”

So he didn’t embellish. He didn’t experiment. And then he judged himself for the outcome a year later — no nominations, no record deal, no TV role. “I played it safe because I was afraid of making mistakes,” he says. “And if you perform afraid of making mistakes, you’ve lost already.

“The point of performing is to be ambitious,” he adds, “to reach, to strive. Whether you achieve your goal or not, the beauty is in the endeavor. That’s what people are here to see. They’re not here to see perfection. They’re here to see life, and life is rarely perfect.”

Going to London later that year to play the lead in The Scottsboro Boys — a much smaller piece about the infamous trial of nine black teens who were wrongfully accused and imprisoned in the 1930s — grounded him.

“I went from this large-scale, Hollywood, Detroitesque superstar expensive musical to a very cheap run on the West End, but with a group of teenagers who I had to help really understand the work itself and then understand how to do the work,” he says. “It reoriented my ‘why,’ I guess: why I’m here, what I’m doing. And I just reopened my door to ambition and to experimentation and to the joy of performing.”

Dixon’s crisis changed him in more ways than one. During their Motown run, he and Adams founded the multimedia production company WalkRunFly. “We’ve worked on projects about James Brown, Sam Cooke and Ray Charles. The constant with all those individuals was the hope of ownership,” Dixon says. “The importance of owning your own creativity. Control over your destiny.”

A critical focus is developing early work by early-stage artists. “The idea was, if they’re walking, we can help them run, and then they’ll fly,” Adams says. In addition to producing flashy musicals like The Hunger Games stage adaptation (and winning a Tony for producing Hedwig and the Angry Inch starring Neil Patrick Harris), Dixon and Adams are producing Whorl Inside a Loop, a play about a men’s maximum-security prison. Their shared commitment to prison reform bonded the two when they met through a mutual friend 12 years ago. “It was really fantastic to meet somebody who was not just, ‘Oh, I’m a performer, let’s talk about Broadway,’” Adams says. “Brandon’s an extremely intelligent person, and he has a vast knowledge of the world outside just entertainment.”

For the multi-hyphenate activist-actor-producer, playing veep Aaron Burr — and addressing veep Mike Pence — are experiences that will stay with Dixon forever, he says: “What Hamilton allowed me to do is to extend my reach and speak to greater numbers of people and be able to look people in their eyes and say things like, ‘Your voice matters, your potential is limitless,’ and to say things like,‘We are greater together than we are apart,’ and to say things like, ‘You are not alone, as much as you may think that.’”

Dixon understands how blessed he is to speak on behalf of so many. “Warren and I have been fortunate enough where we can walk into certain rooms, and not everybody who does what we do can — not everybody who looks like we do can — and it is crucial that we create platforms for the people around us to walk through those doors,” Dixon says. “You got to bring people with you, you know? It’s imperative. We are our brother’s keeper.

“If you are not working to create a space for somebody to live better, to find their dreams, to have a home, to create love in the world, to create a partnership with another individual, then you are wasting your time, you are wasting your money,” he continues, voice rising. “Stacking money you’re hoarding in a vault — that makes no sense.”

With a mischievous grin, he adds: “This republic’s probably only going to last another 20, 30 years. So while the dollar still can do something, you better spread that shit around.”

Yelena Shuster ’09 has written for The New York Times, Cosmopolitan, InStyle and more. She runs TheAdmissions Guru.com, where she edits admissions essays for high school, college and graduate school applications.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu