The Class of 1919 Professor of Political Science, Nathan is an expert in Chinese politics and foreign policy

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

The Class of 1919 Professor of Political Science, Nathan is an expert in Chinese politics and foreign policy

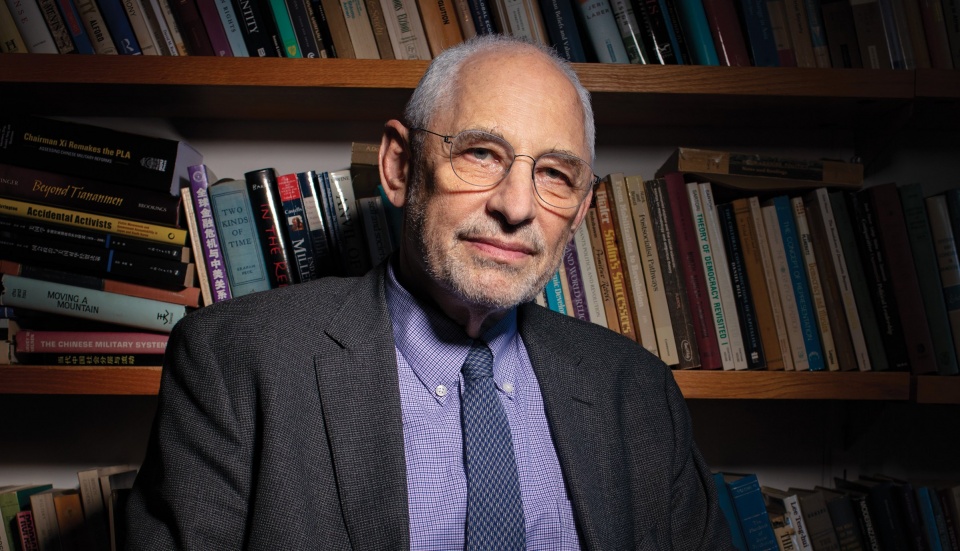

JÖRG MEYER

Andrew J. Nathan has been teaching at Columbia for nearly 50 years; as he points out, he was even born in Columbia-Presbyterian hospital. The Class of 1919 Professor of Political Science, Nathan is an expert in Chinese politics and foreign policy; he teaches students from the College, Barnard, GS, SIPA and GSAS about China, political participation, political culture and human rights.

Nathan became interested in China somewhat by accident. His father was “a spiritually questing” person who read about Zen Buddhism. As a first-year Harvard sophomore (“I was allowed to skip my freshman year — a bad idea”), Nathan needed a social science class; remembering his father’s fascination with the Orient, he signed up for “History of East Asia.”

“In 1960, that seemed very exotic,” he says. It turned out to be his favorite course.

Nathan declared a major in history with a focus on modern China, and began studying intensive Chinese — one of only a few undergraduates to invest in a seemingly useless language at a time when the United States and China had no friendly contact. Upon graduation, Nathan was awarded a fellowship to study in Hong Kong; when he returned to Harvard for a master’s in East Asian studies, his advisor suggested he get a Ph.D. in political science. “I did definitely enjoy the study of China,” Nathan says. “But it took years of teaching for me to get into the poli sci part.”

He taught at the University of Michigan as a post-doc before being hired at Columbia in 1971. Early on in his College career, Nathan was asked to teach Contemporary Civilization. “It was a struggle at first because I hadn’t had a broad liberal arts education,” he says. But he grew to love it, and has taught it since.

Nathan has helped generations of young people to better understand China and the world they live in; he won the Mark Van Doren Award for Teaching in 2008. “My students have gone into teaching, into the media, into think tanks, the State Department, the CIA,” he says. (He didn’t teach Barack Obama ’83, “but I participated in a briefing for him when he was President.”) “You don’t change the world as a college professor,” he says. “But I feel like I’ve had the opportunity to say what I want to say and be listened to, and that’s been a privilege.

“Those semesters in CC when students are reading Rousseau or Nietzsche and you see them get hooked, when the conversation gets going and you can just duck under the table and let the conversation rip, that’s very cool,” Nathan adds. “The connectivity of it is extraordinarily gratifying.”

Nathan has chaired, directed and served in various leadership roles across Columbia. He is currently part of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, which facilitates teaching and research on East, Southeast and Inner Asia; and is on the board of advisors for the Institute for the Study of Human Rights, which provides interdisciplinary human rights education. ISHR’s Advocates Program brings activists from all over the world to campus in the fall semester, and Nathan welcomes them as guest speakers in his “Introduction to Human Rights” course. “Students get to see the actual people who do the work they’re studying,” he says.

Despite his deep connection to China, Nathan has been banned from entering the country since 2001, after the publication of The Tiananmen Papers, the book he co-edited with Perry Link. A whistle-blower approached Nathan with documents exposing the political process around the 1989 Tiananmen crisis; Nathan spent several years authenticating the material and supervising the translation with his friend Link, then a professor of East Asian studies at Princeton. When the story broke it got a lot of attention — The New York Times ran a front-page article and Nathan appeared on 60 Minutes — which resulted in both Nathan and Link being barred.

“Some Chinese officials have said they want to give me a visa — maybe they think it’s been long enough, or they like what I did — but they don’t dare unless someone above them takes responsibility, and that hasn’t happened,” Nathan says. “I never push it. I’m waiting for an invitation. It would be good to go and get a more tangible sense of the mood, but I can continue my work without being there in person.”

Nathan has authored more than a dozen less controversial books (most recently, 2012’s China’s Search for Security) and regularly publishes in academic journals. He’s the Asia/Pacific book reviewer for Foreign Affairs, and contributes articles to its website to help readers understand China’s point of view on subjects such as the recent protests in Hong Kong.

Outside the classroom, Nathan stays busy with his four children (son Oliver is a College senior; daughter Alexa is a Barnard grad) and one grandchild. He loves museums, and hopes to take art history courses when he retires — whenever that is. “I’m 76, but teaching is too much fun to stop now!”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu