How Contemporary Civilization laid the foundation for the Core Curriculum.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

How Contemporary Civilization laid the foundation for the Core Curriculum.

The view from Alma Mater in 1919.

Images COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

Plato versus Aristotle on the polis. Augustine versus Aquinas on God and the soul. Hobbes, Locke and Rousseau thrashing out the leaders and the led. Darwin finding our place among the beasts.

This is the stuff of “Introduction to Contemporary Civilization in the West,” aka Contemporary Civilization, aka CC. For the last 100 years, every Columbia College student has alternately sweated through, fretted over, grappled with and (often enough) reveled in this unique required backbone of a College education. It is also, significantly, the first pillar in what became the Core Curriculum. Its success laid the foundation upon which first Literature Humanities, in 1937, and later Art Humanities and Music Humanities would be built. It both offered a model for how those classes might be conducted and inspired an educational purpose apart from pre-professional training: to equip students with intellectual awareness and habits of mind that would be valuable throughout their lives.

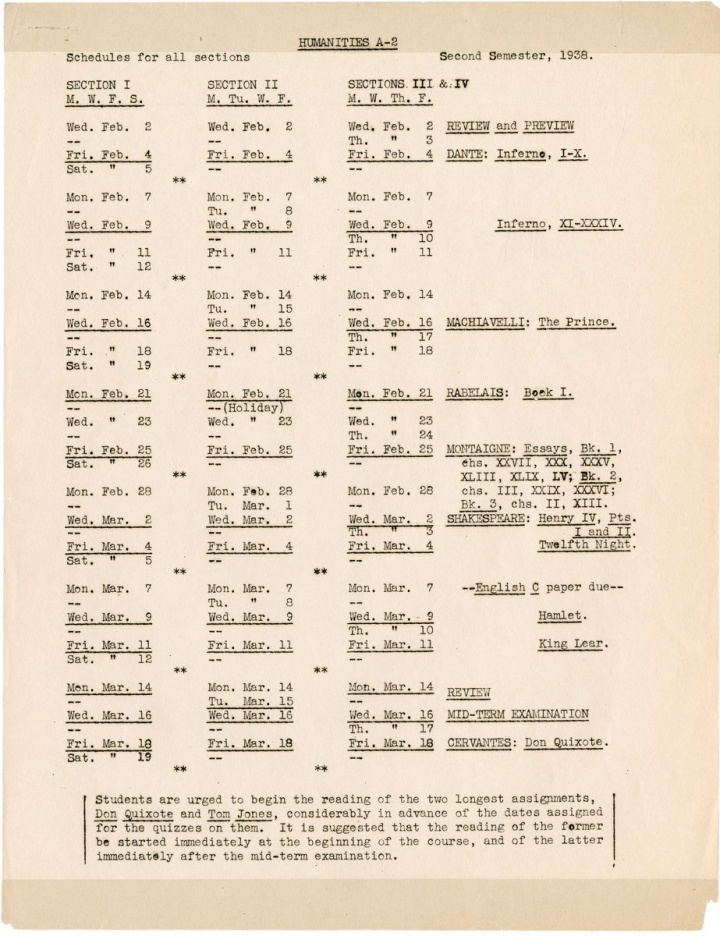

It turns out that for all the continuity and commonality CC has provided through the years, the course has traveled far from its original design. Students have read primary texts in full only since 1968, spending bleary-eyed nights with works like Machiavelli’s The Prince and Descartes’s Discourse on the Method. For roughly 20 years before that, CC’s raw material was found in two Columbia-published casebooks (“The Red Books”) that summarized, wove together and offered excerpts from seminal thinkers. Both of these iterations of the class would be nearly unrecognizable to its earliest enrollees.

That’s because when CC was unveiled in 1919, immediately following the First World War, it had a highly specific purpose and what was then a radically different approach to undergraduate education. It was meant to instill in the College’s first post-bellum classes a fundamental awareness of their essential place in the modern human race — the better to help them forestall another global conflagration and to prepare them in case one did explode.

And yet, however foreign it may be to today’s eyes, the embryonic CC of a century ago foreshadowed the CC of 2019. From the beginning, the course has sought to introduce young minds to some of humankind’s most essential, intractable questions and dilemmas.

CC was the byproduct of the unprecedented carnage and social upheaval of the Great War. Millions were killed. Empires fell. A generation was strangled. Some 200 uniformed alumni from across the University died. When the smoke literally cleared on November 11, 1918, “the war to end all wars” was not just a catchphrase.

The University had done its part. In 1917, Columbia had introduced the Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.), a government-sponsored experiment in educating citizen-soldiers that essentially consisted of uniformed students taking regular courses. Part of the instruction was a class called “War Aims” that was designed, by one account, to promote “understanding the worth of the cause for which one is fighting.”

Dean Herbert Hawkes was instrumental in the founding of CC.

And so the College faculty determined that “War Aims” should yield to an undefined yet mandated course that would consider the modern world.

This metamorphosis, constituting the first step toward Contemporary Civilization, took place during crucial junctures in both College and University history. At the time, many elite colleges still doubled as finishing schools that would somehow “turn boys into men.” Scholarship often came second to the hazy notion of building character.

But character couldn’t always be built. And Columbia’s imperious president, Nicholas Murray Butler CC 1882 — whose tenure lasted from 1902 to 1945 — cared little for budding maturity. Rather, he was concerned with molding his growing university into a grown-up, graduate-focused, research-oriented colossus. Indeed, “Nicholas Miraculous” once accused undergraduates of “intellectual dawdling.” Under his (unrealized) “Columbia Plan” of 1905, College students could enter the University’s professional or graduate programs after their sophomore year. As late as 1917, Butler was still proposing a separate two-year junior college for precisely this purpose.

The end of WWI raised questions about peacetime education at the College.

It was against this knotty institutional background that Contemporary Civilization was hatched. Just two months after the Armistice, on January 20, 1919, the College faculty resolved that a course called Contemporary Civilization would now be a freshman requirement. (The name itself was punted around a bit; other candidates were “Contemporary History,” “The World We Live In” and, naturally, “Peace Issues.”) CC even won the endorsement of Butler, who shook off his lack of interest in undergraduates enough to approve of their taking a wider view of the world around them; a Jester cartoon depicted him deploying the new course as a weapon against Bolshevism.

Professor of Philosophy John J. Coss was the first director of CC.

With an average of 15 students, each section was small enough to be conducted as a discussion. Sections would meet five times a week, 9–10 a.m., complete with daily quizzes. The 1919–20 “College Announcement” made clear the ultimate goal: “To inform the student of the more outstanding and influential factors of his physical and social environment. By thus giving the student objective material on which to base his own judgment, it is thought he will be aided in an intelligent participation in the civilization of his own day.”

The first-year students drew upon a primer of some 450 pages that was prepared especially for their new class. It was Human Traits and Their Social Significance, written during summer 1919 by campus philosopher Irwin Edman CC 1916, GSAS 1920. Not yet 23, he wouldn’t earn his Ph.D. for another year, yet he was charged with writing a seminal book. “To my surprise,” he recalled, “I found myself under forced draft … [writing] a book for the section of the course for which, apparently, no viable text existed.”

Irwin Edman CC 1916, GSAS 1920 wrote the book — literally — on CC; his was the first text used for the course.

CCT ARCHIVES

Edman’s tome offered such heady chapters as “The Demand for Privacy and Individuality,” “The Development of the ‘Self,’” “Art and the Aesthetic Experience” and “Morals and Moral Valuation.” It was an audacious, broad-ranging and, in many respects, idiosyncratic effort. The first two weeks of the very first incarnation of Contemporary Civilization were devoted to discussing the physical features of planet Earth and the natural resources of its major countries.

Other volumes written by College faculty and graduates — many of them written specifically for CC — soon supplemented Edman’s. Among these were Man and Civilization by anthropologist John Storck CC 1922, GSAS 1929, which influenced the class’s growing tendency to look further into the past in order to understand the present; and The Making of the Modern Mind by Professor of Philosophy John Herman Randall Jr. CC 1918, GSAS 1922.

“These texts were not easy reading,” wrote J.W. (“Wim”) Smit, who famously taught all four of the basic Core Curriculum courses. “The first CC students worked hard. The sheer mass of problems thrown at them was daunting, involving much more than a passing acquaintance with European and American history, social psychology, world geography, philosophy, economics and politics.”

Despite the burden, the College’s charges seemed to respond. Just six weeks into the fall semester of the foundational year of 1919, Coss offered a glowing assessment in the Columbia University Quarterly: “It is not too early to state that even the most sanguine advocates of this innovation in freshman education are surprised by the success.” He credited the major part of the success to the fact that the students liked the material, adding: “As one rather clever freshman put it, ‘I like this course because it is new and my professor is still interested in it; he is not just going over the same old thing again.’”

Coss praised the “unusually competent group of men” who were teaching this strange new construct. But his most personal thoughts were reserved for the hundreds of teenagers who were actually taking it. Among these were such CC 1923 legends as composer Richard Rodgers, Oscar-winning screenwriter Sidney Buchman, humorist Corey Ford and philosopher Mortimer Adler, who developed his own concepts of canonical texts that were eventually introduced to St. John’s College in Annapolis.

“[A] reason for the success of the course which must not be overlooked,” wrote Coss, “is to be sought in the very nature of the freshman class, which is unusually intelligent and mature. The maturity doubtless comes in part from the four years that have just passed. The war and its issues have made even boys thoughtful, and the social unrest which has come with peace has intensified reflections.”

Contemporary Civilization was on its way. Through word of mouth, speeches at academic conferences, attention in scholarly journals and general press coverage, the news about CC spread. Shortly before Christmas 1919, Hawkes estimated that more than 100 colleges and schools across the nation had requested detailed information about it. By 1921, Spectator was calling CC “famous” and noted that Hawkes was getting about 10 letters of inquiry per week. “Rutgers College has adopted the Columbia syllabus,” Spec wrote, “and Yale, Dartmouth, Princeton, Chicago, and Johns Hopkins have worked out courses quite similar to Columbia’s.”

The University published a summary of the CC experiment in 1920 as Introduction to Contemporary Civilization: A Syllabus. “At 121 pages, followed by 32 pages of statistics,” wrote Thomas Paul Bonfiglio in Why Is English Literature? (2013), “this may be a candidate for the longest course syllabus in the country.” The whole notion of CC itself, Bonfiglio wrote, constituted “a tectonic shift in the foundations of university education.” That shift, however, was not a matter of drilling the thoughts of the many names that adorn the facades of Butler Library into undergraduate heads. Instead, this was a matter of abandoning classical learning, including the reading of “dead” languages like Greek and Latin, and yanking undergraduates into an urgent, present-day life.

CC provided a model for the course that became Literature Humanities, introduced in 1937.

Not everyone on campus was enamored. Some faculty said the course was unteachable, or worried that it would serve as an alternative rather than an enticement to deeper scholarly studies. But the balance in favor of CC — which by the mid-1920s was ranked by graduating seniors as the most valuable class at Columbia — far outweighed any skepticism. Contemporary Civilization would gradually, and inevitably, make its mark. As founding figure Edman himself put it, “The incoming freshmen had the sense of participating in a new and exciting educational adventure … Within a year or two Columbia College seemed always to have had a course in CC.”

What’s more, although no one planned it that way, Contemporary Civilization — and the wider Core Curriculum that followed — gave Columbia College something it had never quite had before: a unique intellectual and even institutional identity. Change was in the air, and on the heels of CC began the shift in how humanities were taught, starting with an honors course that emphasized reading classics in translation, without secondary sources — the predecessor to Literature Humanities. By 1947, the four main pillars of the Core had been established.

Indeed, as philosophy professor Justus Buchler GSAS’39 wrote in 1954, reflecting on CC for an essay composed for the University’s bicentennial, “The year 1919 can be justly regarded as marking the actual birth of the new Columbia College.”

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu