Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

The Core’s Great Community

Core Curriculum director Larry Jackson

Emma Asher

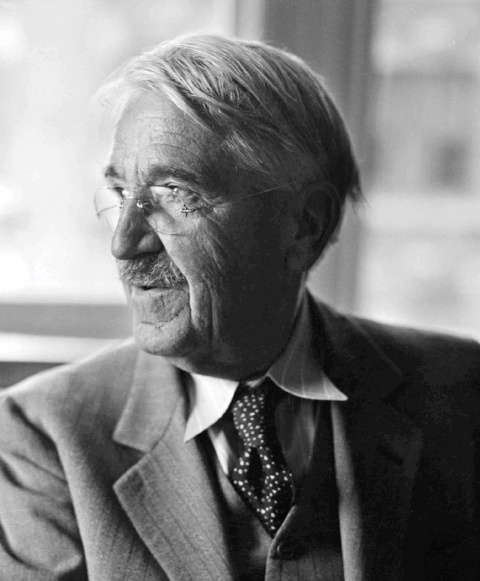

Philosopher John Dewey thought democracy could survive only if we foster a “great community.”

BETTMANN / GETTY IMAGES

And, of course, this community is not restricted to Morningside Heights. It extends across generations and continents to include all of you, our alumni.

I had a chance to see just how large and influential our Core community is during a recent visit to Sabancı University in Istanbul. For 25 years, Sabancı has offered a unique liberal arts education to students in an academic context that often stresses specialized professional training over free curricular exploration. I spoke with one of the university’s founding deans, a Columbia College alumnus, who told me that he and his colleagues were inspired by our Core to develop a similar general education program for Sabancı’s undergraduates, which they named the Foundations Development Program. It was moving to meet their students and hear how much the liberal arts education that we often take for granted at Columbia has opened their minds and changed their lives.

Something else we too often take for granted at Columbia is academic freedom. A little more than a decade ago, 1,000 Turkish academics, including 30 professors at Sabancı, signed a petition calling for the government to peacefully resolve its conflict with the Kurds. The signers of the Academics for Peace petition were investigated and hundreds were charged with terrorism. Public universities were forced to fire petitioners, but Sabancı stood firm, and the faculty members who signed the petition kept their jobs.

Sabancı is one of several universities that we are now partnering with as we carry on the Core’s tradition of grappling with the challenges and debates taking place in higher education. When the College established the Core in 1919 as a single course, Contemporary Civilization, the idea was to prepare students for “the insistent problems of the present.” These included the catastrophic fallout of WWI, a deadly flu pandemic, a political crackdown on dissent and immigration in the United States, and anti-Black violence at the hands of vigilantes and police. But the Core also grew out of a newly emerging debate about the aims and methods of education. In the early years of the 20th century, educators and social reformers considered how best to teach the youth of a modern democratic society that was facing increasingly complex problems that would require new forms of expertise, innovation and, most importantly, social cooperation.

Today, we grapple with similar crises, and debates about the role of education in democratic life continue. Books are being banned in schools and libraries. Humanities programs are being shuttered. Artificial intelligence threatens the honest and original development of ideas. These are the kinds of problems that we will discuss in our classes and faculty meetings, and with partners like Sabancı, this year.

After returning from Istanbul and seeing the twin pressures of specialized professional training and anti-democratic politics that liberal arts universities there are facing, I am especially appreciative of the kind of education that we are able to offer at the College, and for the kind of community that it fosters — one based on the respectful exchange of diverse ideas and perspectives.

It is also clear to me that the stakes of what we do here could not be higher, that the simple act of sitting in a classroom with 20 peers discussing ideas can be the beginning of a great, democratic community that can have an impact on the wider world.

Issue Contents

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu