|

COVER STORYSTAND COLUMBIA: THE FOUNDING OF KING'S COLLEGEBY ROBERT McCAUGHEY Providence has not called us alone

to found a University in The clamour I raised against [the

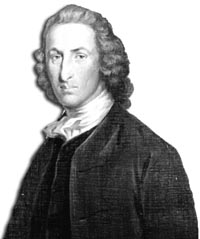

College] … when it was Columbia College, founded as King’s College in 1754, had a long and eventful history before it was even officially established and ready to accept students. In anticipation of Columbia’s 250th anniversary, Robert McCaughey, Anne Whitney Olin Professor of History at Barnard, undertook six years ago to write an interpretive history of the University. The result is Stand, Columbia (Columbia University Press, 2003, $39.95), which traces the evolution of Columbia from its beginnings as Tory redoubt in revolutionary America through its Knickerbocker days down to the Civil War, its emergence as America’s first multiversity by the early 1900s, through its multiple crises in the 1960s and on to its current position as a global university at the outset of the 21st century. The following excerpt from the first chapter details the events that led to the College’s founding. PROLOGUEColumbia’s has been a disputatious history. Even the designation of its pre-founder has two opposing candidates. The one far more often cited for this distinction has been Colonel Lewis Morris (1671–1746), a considerable presence in the public life of both early 18th century New York and New Jersey. The claims of his being the pre-founder of Columbia turn on a 1704 letter he wrote to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPGFP), the missionary arm of the Anglican Church established in 1701 in London, where he writes: “New York is the centre of English America and a fit place for a Colledge.”

Lewis Morris, the first lord of Morrisania Manor (now much of the Bronx), makes for the relatively more attractive pre-founder. This is in part because of his reputation as the early leader of New York’s “Country” party and doughty champion of the popular cause in the colonial assemblies of New York and New Jersey against the “Court” party centered in the Governor’s Council aligned with a string of supposedly corrupt and power-grabbing governors. His being the grandfather of the King’s College graduate (1766) and revolutionary statesman Gouverneur Morris (1752–1816) and ancestor of numerous other Morrises and Ogdens who figure in Columbia’s subsequent history further strengthens his case. Mid-19th century Columbia Trustees Lewis M. Rutherford and Gouverneur M. Ogden were direct descendants. Morris’s recommendation of New York City as “a fit place for a Colledge” occurred in the middle of delicate negotiations involving the 32-acre “Queen’s Farm” on Manhattan’s West Side, running east to west from Broadway to the Hudson River and north to south from modern-day Fulton Street to approximately Christopher Street. ... Named the King’s Farm — for King William — when it was laid out in 1693 and renamed Queen’s Farm on Anne’s accession to the throne in 1702, the farm was assumed to be in the gift of the Royal Governor of New York. It became a source of political conflict in 1697 when Governor John Fletcher (1692–98) leased it to Trinity Church, New York’s first Anglican parish, for seven years. The City’s non-Anglicans, who constituted a substantial majority, thought the royal authorities had already been more than generous to Trinity Church in providing its rector, through the Ministry Act of 1693, with a salary derived from general tax revenues, and, in 1796, with a royal charter for the church itself. Meanwhile, the City’s Dissenting majority were expected to make do without either public support for their ministers or the security of a royal charter for their churches. New Yorkers opposed to the lease had looked to Fletcher’s successor, Governor Richard Coote (1698–1701), the Earl of Bellomont, a Whig and “no friend of the Church,” to take back the land when the lease expired. But before Bellomont could do so, he died in 1701. His successor was Edward Hyde (1702–08), the Earl of Cornbury, a “stalwart Churchman” and cousin of Queen Anne. Shortly after his arrival in New York in May 1702, Governor Cornbury took up the matter of the farm. The rector of Trinity Church, the Reverend William Vesey (1696–1742), and most of the church’s vestrymen hoped the new governor would simply deed the farm permanently to the church for whatever uses it deemed fit. Although himself a vestryman, Morris seems to have wanted it to go to the SPGFP and made his point about New York being “a fit place for a Colledge” as an argument for the society’s acquiring the farm. Indeed, his letter may have been intended to thwart Cornbury’s already announced plan, which was to cede the farm to Trinity Church. Evidence of Cornbury’s intentions is contained in the records of Trinity Church for February 19, 1703: “It being moved which way the King’s farme which is now vested in Trinity Church should be let to Farm. It was unanimously agreed that the Rector and Church wardens should wait upon my Lord Cornbury, the Govr to know what part thereof his Lordship did design towards the Colledge which his Lordship designs to have built.” While Morris’s letter has been described as having been written in 1702, a few months before the Trinity Church entry, it now seems clear that it was not written until June 1704, more than a year later. But even assuming the earlier date, the letter was written after Cornbury’s assumption of his governorship and almost certainly after he had revealed his own plans for the farm. Moreover, Morris only mentioned a possible use for a portion of a piece of property over which he had no control — only designs — whereas Cornbury had it in his gift to dispose of the property as he saw fit. The Trinity Church entry makes clear that his “design for the Colledge” was already well known and that the church recognized the need to be responsive to it. Thus Cornbury’s claim to being the pre-founder of New York’s first college seems at least as strong as that of Morris. Why, then, is he so seldom mentioned in this regard? … Before proceeding to the actual founding of New York’s “colledge,” three points of a more general nature might be made about Morris’s endorsement of the idea. The first is the stress he put on geographical location. By the “center of English America,” Morris was reminding his London correspondents of New York’s advantageous location between the Crown’s New England colonies and those to the South around Chesapeake Bay, in the Carolinas and the West Indies. Should someone in England wish to underwrite a college for all of English America, or establish permanent military presence there, or install a bishop, where better than New York?

The second is the already alluded to point that the idea for a college was linked to a New York City real estate transaction. New York City real estate and the political economy of New York City play a central role throughout all of Columbia’s history, if somewhat diminished after 1985 with the sale by the University of the land upon which Rockefeller Center stands. The third point is that Morris’s endorsement occurred more than four decades before another New Yorker is again heard on the subject of a college — and a full half century before the colony acquired its own college. Morris did not exactly start a rush to college-building among his fellow New Yorkers. Then again, he had more than one purpose in mind. New Yorkers usually do. … COLLEGE ENTHUSIASMNew York’s focus on the commercial main chance, its religious pluralism and demographic character all likely contributed to the nine-decade lag between its establishment as an English colony and the emergence of any sustained interest in a college. The Puritans of Massachusetts Bay had allowed only six years to lapse between settlement in Boston and the 1636 founding of Harvard College. They did so, as they stated in the first fundraising document produced by an American college, New Englands First Fruits, both “to advance Learning and perpetuate it to Posterity” and so as not “to leave an illiterate Ministry to the Churches, when our present Ministers shall lie in the Dust.” Not trusting Anglican Oxford or even the more Puritan-leaning Cambridge to train their Congregational clergy and magistrates, they invented the local means to do so. A similar impulse prompted the establishment in Virginia of the College of William and Mary in 1693, by which time Virginian Anglicans had tired of their reliance on the dregs of the English episcopacy to fill their pulpits and sought (unsuccessfully, as it turned out) to provide themselves with a learned homegrown clergy. And so it was again, in 1701, when an increasingly Arminian-leaning Harvard no longer met the religious standards of Connecticut’s unreconstructed Calvinists, many of them Harvard graduates, that the “Collegiate School” that would become Yale College came into being. Its opening ended the first wave of college-making in pre-Revolutionary America. More than four decades passed between the founding of the first three American colleges and the next six, which together constituted the nine colleges chartered prior to the Revolution. For much of that intervening time, three seemed enough. Even with William and Mary’s early slide into a grammar school, Harvard and Yale seemed fully capable of absorbing the limited demand for college-going that existed throughout the northern colonies, while the occasional Southerner resorted to Oxford, Cambridge or the Inns of Court for his advanced instruction. What restarted colonial college-making in the 1740s — what Yale’s worried Ezra Stilles called “college enthusiasm” — was the Great Awakening, a religious upheaval within American Protestantism that divided older churches, their settled clergy and their often formulaic liturgical ways from the dissident founders of upstart churches, their itinerant clergy and their evangelical enthusiasms. The first collegiate issue of the Great Awakening was the College of New Jersey (later, Princeton), which was founded in 1746 by “New Light” Presbyterians of New Jersey and New York. They did so in protest against “Old Light” Yale’s hostility to the preaching of the English itinerant George Whitefield and his even more flamboyant ministerial emulators. These included Gilbert Tennent (1703–64) and his brother William (1705–77), founders of Pennsylvania’s “Log College,” from which Princeton traces its prehistory. The subsequent foundings of the College of Rhode Island (later Brown) by Baptists in 1764, of Queens College (later Rutgers) by a revivalist wing of the Dutch Reformed Church in 1766 and of Dartmouth by “New Side” Congregationalists in 1769 are all the products of the mid-century religious ferment that seized the dissenting branches of American Protestantism. Two other colleges founded in this second wave of colonial college-making reflect more secular, civic considerations. There is some merit to the case made by University of Pennsylvania historians in claiming Benjamin Franklin as founder, if less for a founding date of 1740. The latter claim — which would have Penn jump from sixth to fourth in the precedence list of American colleges — requires dating its founding to the Presbyterian-backed Charity School built in Philadelphia in 1740. It is this soon-moribund institution that Franklin transformed into the municipally funded Philadelphia Academy in 1749 and that was chartered in the spring of 1755 under joint “Old Light” Presbyterian and Anglican auspices as the College of Philadelphia. By then, however, New Yorkers had sufficiently bestirred themselves to have anticipated their Philadelphia rivals by some months in the chartering of yet another college, to whose history we now turn. The founding of Harvard in 1636 and Yale in 1701 had set no competitive juices flowing among New York’s merchants. But the announcement in the summer of 1745 that New Jersey, which had only seven years before secured a government separate from New York’s and was still considered by New Yorkers to be within its cultural catch basin, was about to have its own college demanded an immediate response. On March 13, 1745, James Alexander (1691–1756), a leading New York City attorney and pew holder of Trinity Church, altered his will to offset his earlier £50 contribution to the construction fund for the proposed college in New Jersey, where he had extensive land holdings and a growing legal practice, with a commitment of £100 to support a similar college in New York. The following October, on the very day that the New Jersey Assembly approved a charter for the College of New Jersey, the New York Assembly took up discussion of a college of its own. In December, the Assembly, with the backing of Governor George Clinton (1741–53), authorized a provincial lottery to raise £2,250 “for the encouragement of learning, and towards the founding [of] a college.”

The Assembly’s actions in support of a new college left unaddressed the matters of its site and denominational auspices. The first prompted three separate proposals in the months following the establishment of the lottery. The first came from the scientist and provincial officeholder Cadwallader Colden (1688–1776), who recommended as a site for the college his adopted Newburgh, 40 miles up the Hudson. The Reverend James Wetmore weighed in shortly thereafter in favor of establishing the college in the Westchester village of Rye, adjacent to the Boston Post Road. The Reverend Samuel Seabury (1729–96) then called for its establishment in the Long Island village of Hempstead. Although all three were Anglicans, Wetmore and Seabury being Anglican clergy, none seems to have been as interested in pressing specifically Anglican auspices for the college (although they may have assumed them) as they were in assuring it a rural setting well removed from New York City. With the last of these proposals, Seabury’s in 1748, public discussion of the college all but ceased. Momentarily embarrassed three years earlier by the New Jersey initiative and still more recently by Franklin’s efforts at college-making in Philadelphia, most New Yorkers seemed once again preoccupied with their various commercial enterprises to the exclusion of any culturally uplifting projects. Not so William Livingston (1723–90). WILLIAM LIVINGSTON: ANTI-FOUNDERColumbia’s story often departs

from the typical collegiate saga. So with its founding.

Most are recounted in terms of the determined and

ultimately successful efforts of a founder, founders

or benefactors. So it is with John Harvard’s

timely benefaction of £800 in 1638 to the

Massachusetts General Court to support its fledgling

college in Cambridge. So it was with those 10 Connecticut

clergymen and the benefactor Elihu Yale who were

instrumental in the founding of Yale, or with Benjamin

Franklin and the University of Pennsylvania or,

in the case of the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock (1711–1779),

the founder of Dartmouth. Yet the story of Columbia’s

founding is less about the successful efforts of

its founders than

Livingston was an odd duck — a tall, hawk-faced, dark complexioned cultural uplifter and moral scold in a city full of roly-poly, flush faced, live-and-let-live money makers. The Loyalist historian Thomas Jones described him as having an “ill-nature, morose, sullen disposition.” Born in Albany in 1723, he was the grandson of Robert Livingston (1673 –1728), the first lord of Livingston Manor, whose 160,000 acres on the east bank of the Hudson above Poughkeepsie made him New York’s second largest landowner. Family ties extended back to the earliest Dutch settlers (among them the Van Rensselaers, who owned the largest of the New York patronships) and forward to the subsequent English mercantile elite centered in Albany and New York City. William followed three brothers to Yale, graduating in 1741. He then settled in New York City where, his brothers already leading merchants, he turned to the law. In 1745, he entered into an apprenticeship with the City’s leading attorney, James Alexander, whose defense a decade earlier of the newspaperman Peter Zenger against charges brought by Governor William Cosby (1690–1736) and his attorney general James DeLancey, had made him a leader of New York’s “Country” party and enemy of the DeLancey-led “Court” party. Livingston’s early professional association with Alexander likely reinforced in him a personal commitment to civil libertarianism. His family’s position in colonial New York politics, however, identified him with the popular cause of the elected Assembly, which rural landowners controlled and which was perpetually at odds with the Governor’s Council, dominated by urban merchants. Livingston demonstrated throughout his life a streak of perverse independence. Early in his legal apprenticeship, he took it upon himself publicly to reprove the socially pretentious wife of his mentor, James Alexander. He thereafter shifted his legal apprenticeship to William Smith Sr. (1697–1769) whose politics, like Alexander’s, aligned him with the popular or anti-Court cause. That William’s branch of the Livingstons consisted of either thoroughgoing Calvinists of the Dutch Reformed or, as in his case, the Presbyterian persuasion, further fueled his antipathy to the Anglican elite of the City. Indeed, Livingston’s lifelong anti-Anglicanism was exceeded only by his rabid anti-Catholicism, both of which he readily accommodated within an even more comprehensive anti-clericalism. Livingston initially looked upon Alexander’s 1745 proposal to construct a college as socially uplifting. It was of a piece with his own efforts three years later to interest New York’s young professionals in forming a “Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge” as an alternative to their degenerating into tavern-frequenting “bumper men.” In 1749, hoping to revive a flagging project, he anonymously published Some Serious Thoughts on the Design of Erecting a College in the Province of New York. In it, he included among the many benefits to be derived from a college its deflecting the city’s unruly young from “the practice of breaking windows and wresting off knockers.” In the fall of 1751, the New York Assembly appointed a 10-member Lottery Commission to manage the lottery funds already accrued to the College — some £3,443.18s — and to decide upon an appropriate site. Livingston was named one of the 10 commissioners, in recognition of his ongoing interest in the project and his family’s standing in the Assembly. He was the only Presbyterian commissioner, with two others Dutch Reformed, and the remaining seven Anglicans (including five members of Trinity Church). This lopsided arrangement (Anglicans represented barely 10 percent of the province’s population) would subsequently be cited as evidence of the prior existence of a secret plot by Anglicans to use public funds to create a “College of Trinity Church.” It is noteworthy, however, that Livingston, suspicious by nature, quietly took up his commission and turned to the task of bringing a college of the New York Assembly’s conceiving into being. In March of 1752, the vestrymen of

Trinity Church offered the Lottery Commission the

northern most six acres of its Queen’s Farm

property as the site for the new college. No conditions

then being set on the offer, Livingston joined the

other commissioners in accepting it. That also settled

the matter of the college’s location, with

all 10 commissioners concurring that it would be

in New York City on the site provided, which was

seven blocks north of Trinity Church and just above

the moving edge of commercial development. On October 24, 1752, another William Smith (1721–1803), this one an Anglican Scot and newcomer to New York employed as a tutor by the DeLanceys, published Some Thoughts on Education: With Reasons for Erecting a College in This Province. The college he proposed would be under Anglican control and incorporated with a royal charter. When these assumptions were repeated two weeks later in a letter to the New-York Mercury, Smith added the suggestion that the Reverend Samuel Johnson (1696–1772), a prominent Anglican minister from Stratford, Conn., be appointed head of the college. As to the source of a salary sufficient to attract Johnson to New York, Smith helpfully proposed that Johnson might be given a joint appointment at Trinity Church. The cat was out of the bag. SAMUEL JOHNSON AND THE ANGELICAN PROJECTWilliam Livingston was second to no man in divining conspiracies where none existed. In the case of a college for New York, however, paranoia was warranted. For several years prior to 1752, a quiet plan had existed among New York Anglicans to use the Assembly’s funds to found a specifically “Episcopal College.” William Smith likely happened upon the plan during his job hunt in New York City, and either wrote Thoughts on Education to ingratiate himself with the Anglicans privy to the plan or was recruited by these same folks to write it.

There is no question that Samuel Johnson was in on the plan. As early as 1749, he was regularly and proprietarily discussing the establishment of a college with his stepson Benjamin Nicoll (1720–60), a Trinity vestryman and later a Lottery Commissioner, and the Reverend Henry Barclay (1715–1764), the rector of Trinity Church and Johnson’s sometime ministerial student in Connecticut. These discussions extended across the Atlantic to England and included both the Bishop of London, Joseph Secker, who oversaw the religious welfare of the American colonies, and the eminent philosopher and Church of Ireland prelate, George Berkeley, whom Johnson had befriended during his stay in Newport in the 1730s, and who pronounced Johnson singularly suited to preside over “a proper Anglican college” in America. Berkeley’s estimate of Johnson’s standing was widely shared by American Anglicans. He was the best known Anglican minister in the colonies by virtue of seniority, his role as mentor for many of the next generation of ministers, his activities as senior missionary in the Society for the Promotion of the Gospel, and his apologetical writings in defense of the Church of England. Along with Benjamin Franklin and Jonathan Edwards, Johnson was one of only three mid-18th century Americans whose writings received any serious attention in England. He was moreover the best credentialed, if least original, of the three. Unlike Edwards, a Dissenter and a religious “enthusiast,” or Franklin, a free-thinking autodidact who in the early 1750s had yet to win his way into English intellectual circles, Johnson was an ordained minister of the Church of England, the recipient of an M.A. from Oxford in 1722 and of a doctorate from Oxford, awarded in absentia in 1748 upon the appearance in England of his philosophical treatise Elementa Philosophica. (Franklin published the American edition of Johnson’s book, which lost money.) Johnson had the further distinction of being the first American to have a non-scientific article appear in an English learned journal. Johnson, in turn, was all-out Anglophile. Despite his family’s three generations in Connecticut, the first two as Puritans, he regularly referred in his ecclesiastical correspondence to America as “these uncultivated parts” and to England as “home.” Johnson’s life prior to his involvement with King’s College was marked by a single act of religious rebellion, though, as befit the man, even this in the cause of a higher orthodoxy. He was born in 1696 in Guilford, Conn., the son of a prosperous farmer and deacon of the local Congregational Church. At 15, he proceeded to Yale College, from which he was graduated in 1715. For the next three years, he served as a tutor at the College, studied for the Congregational ministry and acted as a substitute preacher until he was called to be the settled minister of the Congregational Church of West Haven. During this period, he and several other Yale friends, influenced by their exposure to Locke, Newton, and Anglican apologists by way of a 1718 gift of books to the Yale Library, found themselves questioning all manner of locally accepted doctrine. In particular, Johnson became concerned about the legitimacy of his own recent ordination by the members of his congregation. Further discussions with a missionary from the Anglican-sponsored Society for the Propagation of the Gospel convinced him that only ordination by an Anglican bishop would do. When Johnson and five other Yaleys, including the just-installed President Timothy Cutler, voiced these views at Yale’s 1722 Commencement, their apostasy became a matter of public record and local scandal. Johnson resigned his West Haven pulpit, bade his congregation farewell and proceeded to England to secure a proper ordination. Upon his return to Connecticut in 1723, he established the colony’s first Anglican church at Stratford. Over the next three decades, he was a vigorous advocate for the Anglican cause, meanwhile providing instruction and encouragement for some dozen young men who followed him out of the Calvinist ranks into the Anglican fold. By 1750, Johnson-trained ministers were rectors of many of the Anglican churches in New England, New York and New Jersey. First and last a denominational polemicist, Johnson was as opposed to the Calvinistic Puritanism of his New England ancestors as he was to the newer “enthusiasms” of the English revivalist George Whitefield and such native-born Great Awakeners as Jonathan Edwards and Gilbert Tennent. His Anglicanism represented a middle way, marked by respect for authority, good order and edifying ritual, without the emotional excess and egalitarian leanings of evangelical revivalism. Others called it “a gentleman’s way to salvation.” Thus, when New York’s Anglicans determined to provide denominational auspices for the college, Johnson was a natural choice to head it. Why Johnson might wish to do so was another matter. At first, he expressed reluctance to exchange the comforts of his Stratford parsonage for the stress of a new job in New York City. His older son, William Samuel Johnson, gave voice to familial reservations when he reminded his father that “Providence has not called us alone to found a University in New York. Nor to urge the slow, cold councils of that city.” Johnson assured his son that he would not resign his Stratford pulpit until installed as president. Johnson’s interest was almost certainly linked to the impact a successfully established Anglican college in New York might have on a campaign he had been waging throughout his ministerial career: to convince the ecclesiastical and political authorities in England that the colonists needed an American bishop. Understandably, this was a minority view among American colonists, most of whom, dissenters from the Church of England, felt themselves well rid of the ecclesiastical authority vested in bishops. That it had been English Dissenters who had effectively blocked Parliament from sending a bishop to the colonies in the early 1740s made the need for such a bishop in Johnson’s mind more palpable. Once installed, he could ordain young men, avoiding the costs and dangers of a sea voyage to England. One of Johnson’s favorite arguments with English ecclesiastical authorities was that five of the 11 colonists sent to England for ordination between 1720 and 1750 had been killed in transit or by disease in England. This was to be the fate of his younger son, Samuel William, in 1756. Johnson further argued that a resident bishop could settle the jurisdictional questions that inevitably arose among the scattered American Anglican clergy, represent the Anglican cause in colonies where Dissenters held political sway and everywhere insist upon the Anglicans’ right to religious practice, all tasks that by default regularly fell to him. And finally, the presence of a locally installed bishop would provide the occasions for the ritual pomp and sartorial elegance that American Anglicans otherwise missed in the “uncultivated wilderness.” Only “the awe of a bishop,” Johnson wrote in 1750, “would abate enthusiasms.” Where such a bishop would reside was not as contentious as one might think. It was generally agreed that he should take up residence where Anglicanism enjoyed a legally protected and socially privileged position. This eliminated all of New England, and Boston, where Dissenters exercised local authority, and also Pennsylvania, and Philadelphia, where William Penn’s charter enshrined the principles of full religious toleration. The Anglican Church was officially established in the southern colonies, but practice had rendered the local Anglican practices barely distinguishable from those of the Dissenters. And anyway, the Southern colonies lacked a city of sufficient size to provide the entourage appropriate to a bishop of the Church of England, and they were at too great a remove from the rest of American Anglicandom. This left New York City, as Lewis Morris had it, “in the centre of English America,” where Anglicans enjoyed local status as the established church. (The Ministry Act of 1693 so provided for the five lower counties of New York, with the rest of the Province operating on a “local option” arrangement.) Trinity Church was the largest and grandest church in the colonies (and the only one possessed of an organ), as well as a separate chapel, St. George’s, and another chapel (St. Paul’s) on the drawing board. The City’s leading families were nearly all either Anglican or Dutch Reformed-on-the-way-to-becoming-Anglican. New York already was the seat of royal government for the colony and headquarters for His Majesty’s Army in North America. Accordingly, the establishment of an Anglican college in the City would, rather like the completion of a skating rink or bobsled run in a competition to become the next Olympics site, sew up New York’s case as British America’s first Anglican see. Who the first American bishop should be was also a question about which there was not much controversy, and especially should he be an American. Apparently Johnson never mentioned the possibility of his own appointment when pressing the case in his frequent communications with the Bishop of London and Archbishop of Canterbury, who would make the appointment. But other American Anglicans were less circumspect, and Samuel Johnson was their odds-on favorite. Thus, his acceptance of the presidency of the proposed college for New York would not only help the cause of the college and advance the case for an American episcopacy, but it would also confirm his position as bishop presumptive. "A HIDEOUS CLAMOUR"The privately hatched plans for “an Episcopal College” already were well advanced when, in the fall of 1752, William Livingston divined it. For his part, the timing was fortuitous. For some three years, Livingston had been discussing the possibility with two fellow attorneys, like him Yale graduates and Presbyterians, John Morrin Scott (1730–84) and William Smith Jr. (1728–93) [this William Smith was the son of the lawyer William Smith Sr., and no relation to the Reverend William Smith] of publishing a weekly newspaper in New York along the lines of the Independent Whig, a London weekly published in the 1720s by the Whig essayists Thomas Gordon and John Trenchard. Like Livingston, Scott and Smith wished to turn their spare time to cultural and political purposes, and the idea of a weekly brought the three into such protracted and noteworthy company that they were long thereafter referred to as “the Triumvirate.” The Independent Reflector was launched in November 1752. By then, Livingston and his comrades-in-ink already had settled on its first major editorial cause. “If it falls into the hands of Churchmen,” Livingston wrote privately to a Dissenting friend on the eve of publishing his first assault upon the College, “it will either ruin the College or the Country, and in fifty years, no Dissenter, however deserving, will be able to get into any office.” The Independent Reflector had been in print for three months before, in its 17th number of March 22, 1753, it offered “Remarks on our Intended COLLEGE.” Prior to doing so, it had attracted a considerable readership and some notoriety for its editorial support for the Moravian minority in New York and for jibes at the office-mongering proclivities of the DeLanceys. And when it did turn to the College, in numbers 17 through 22, the essayist (assumed to be Livingston) began civilly enough. He supported the idea of a college and that it be located in or near New York City. He called for an expansive curriculum, such to render its graduates “better members of society, and useful to the public in proportion to its expense.” Otherwise, “we had better be without it.” He went on to castigate both Harvard and Yale for inculcating their impressionable students in “the Arts of maintaining the Religion of the College” and made similar animadversions against the English universities when they justified the polygamies of Henry VIII and the “jesuitically artful” projects of the popish James II. By contrast, he concluded with respect to New York’s proposed college, “it is of the last importance, that ours be so constituted, that the Fountain being pure, the Streams (to use the language of Scripture) may make glad the City of our GOD.” In the second number, “A Continuation on the Same Subject,” Livingston went to the heart of his complaint with the prospect of a college in the control of a single religious denomination. By listing English and Dutch Calvinists, Anabaptists, Lutherans, Quakers and his recently championed Moravians along with the Anglicans, he implied that each of New York’s religious sects had an equal claim — and thus no sustainable claim — to the sole governance of the College. And should such solitary rights of governance be conferred on any one of these sects, he warned, the College would instantly become “a Nursery of Animosity, Dissention and Disorder.” Moreover, no one would attend but the children of the governing sect, limiting both the college’s enrollment and its potential for advancing the public good. New Yorkers not of that sect, he prophesied, would repair elsewhere for college, never to return. The result would be a “Party-College,” made all the more unacceptable to those not of that party by the public funds that went into its creation and maintenance. Surely, Livingston asked rhetorically, the Legislature could never have intended its proposed college “as an Engine to be exercised for the purposes of a party”? What it must have intended was “a mere civil institution [that] cannot with any tolerable propriety be monopolized by any religious sect.” Such a college, in contrast to a “party-college,” would attract students from the neighboring colonies, among them New Englanders averse to the region’s prevailing Calvinists and Pennsylvanians of all denominations but one (“I should always, for political reasons, exclude Papists”). Such a vast “importation of religious refugees” to flow from the establishment of a nonsectarian college in New York, could not be other than “commendable, advantageous and politic.” In a third essay, “The Same Subject Continued,” Livingston argued against positing the governance of the college in a corporation created by a royal charter. To do so would remove the college from legislative scrutiny and public oversight would be lost. Instead, he proposed in his fourth essay, “A Farther Prosecution of the Same Subject,” that the College be incorporated by an Act of the Assembly. The logic for doing so Livingston presented succinctly: “If the Colony must bear the expense of the College, surely the Legislature will claim the superintendency of it.” To the argument that superintending an educational institution was not the proper business of the legislature, he responded by asking: “Are the rise of Arts, the Improvement of Husbandry, the Increase of Trade, the Advancement of Knowledge in Law, Physic, Morality, Policy, and the Rules of Justice and civil Government, Subjects beneath the Attention of our Legislature?” In his fifth essay, Livingston stipulated

11 terms of incorporation. Chief among them: the

Trustees to be elected by the Legislature; the President’s

election by the Trustees to be subject to legislative

veto; the faculty to be elected by the Trustees

and President; students to “be at perfect

liberty to attend any Protestant Church at their

pleasure”; Divinity not to be taught as a

science. Supporters of an Anglican-controlled college grumbled in private during the six-week assault on them and their eminently reasonable plans for the College. What Livingston had proposed, Johnson reported to his ecclesiastical superiors in London, was nothing short of “a latitudinarian academy” that would exclude religion from its curriculum and churchmen from its governance. Public responses were few and scattered, mostly in the form of anonymous letters in the New-York Mercury written by the Reverends Thomas Bradbury Chandler, James Wetmore, Samuel Seabury and Henry Barclay. All subscribed to the view that all proper colleges possessed a religious character and that, given the favored place of the Anglican church in New York, not to mention its established status in the mother country, New York’s college should be Anglican. All also demonstrated a profound discomfort at having to confront their polemically more effective critics in print. Johnson said he left the “writing in the church’s defense” to his New York promoters, who were, he assured the archbishop of Canterbury, “endeavoring not without some success to defeat their pernicious scheme.” The prolific William Smith came forth with A General Idea of the College of Mirana in April 1753, just as the Independent Reflector series wound down. But he did not directly engage Livingston’s arguments so much as describe a model two-track curriculum for a very different kind of college from the one Livingston had in mind. The first track was designed for those students destined for the learned professions, “divinity, law, physic, and the chief officers of the state,” and would include instruction in dancing and fencing. The second track for those aspiring to the mechanical professions “and all the remaining people of the country,” would have less Latin and be spared instruction in dancing and fencing. Before setting sail for England to take holy orders, the still unemployed Smith commended to his readers the Anglican liturgy for all college services. Samuel Johnson was sufficiently impressed with Smith’s good sense to suggest to his New York co-conspirators that “he would make an excellent tutor.” Too late. Smith by then had already been approached by Benjamin Franklin about a professorship at the Philadelphia Academy, and it was to Philadelphia that he went upon his return to become the Provost of the College of Philadelphia. Rather than mount a full-scale counterattack against the radical ideas advanced by Livingston, the self-described “Anti-Reflectors” put their energies into behind-the-scenes campaigns to get the Independent Reflector shut down. Help came in the form of a suicide. Five days after taking his post as Governor of New York on October 7, 1753, Sir Danvers Osborne took his own life. This brought to power the Acting Governor James DeLancey, the “natural leader of the Episcopal party” and the bete noir of the Livingston-led “popular” or “country” party. DeLancey promptly withdrew all provincial business from the printer of the Independent Reflector, which soon thereafter ceased publication. Although Livingston and William Smith Jr., persisted through 1753 in their attacks on “The College of Trinity Church,” using several public outlets, including a periodical of their own with the catchy title The Occasional Reverberator, the backers of the college pressed on through the fall of 1753. As the war of words continued, the center of action shifted to the Lottery Commission. There, Livingston’s position as the lone commissioner favoring a legislatively directed college put him at a disadvantage. With neither an alternative site to propose nor a presidential candidate of his own, he proceeded with uncharacteristic caution. On November 22, 1753, he moved that the Lottery Commissioners elect Samuel Johnson as their unanimous choice to preside over the new college. He then proposed that Chauncey Whittelsey be elected as the college’s “first tutor.” Both motions were adopted and Livingston was assigned the responsibility of informing the president- and first-tutor elect. Lacking a credible nominee to bring forward, Livingston conceded the number one spot to assure getting his own man in as number two. And who, pray ask, was Chauncey Whittelsey? First, he was not an Anglican clergyman but an “Old Light” Congregationalist merchant residing in New Haven. Second, he had been Livingston’s tutor at Yale and an occasional correspondent since. There might also have been a third credential, though allowing so requires extending to Livingston a sense of humor not evidenced in the historical record or suggested by his grim visage. As Livingston and others, including Johnson, who followed Yale affairs well knew, Whittelsley had played a small but memorable part in Yale’s encounter with the Great Awakening. In 1740, in the immediate wake of George Whitefield’s visit to New Haven, during which he warned against “the dangers of an unconverted ministry,” David Brainerd, a particularly exercised undergraduate (and nephew of Jonathan Edwards) felt moved to conduct a survey on the state of the souls of his teachers. Most passed muster, but Tutor Chauncey Whittelsley, he sadly reported to Yale’s indignant President Thomas Clap, did not have “any more grace than the chair I then lean’d on.” Just the man for New York’s intended college. As it turned out, Livingston’s efforts to plant Whittelsey came to naught when Johnson, in the politest letter imaginable, frightened him off with a description of his expected duties. By then, that is the spring of 1754, Johnson had pretty much completed haggling with the Lottery Commissioners over the terms of his appointment. Too far committed to back off now, especially when his salary demands were met, he nonetheless extracted two further concessions from the Commissioners upon his acceptance of the presidency: the right to take a year’s leave of absence from his Stratford parish rather than resign immediately; and explicit authorization to leave New York whenever smallpox threatened the City. Both bespoke serious reservations about his new home, which would only increase with time. On May 14, 1754, shaken by the “hideous clamour” produced by Livingston’s attacks on the college, the vestrymen of Trinity Church informed the Lottery Commission that their earlier gift of land for the intended college was now subject to two conditions: 1. The president of the College must always be a member of the Church of England; [and] 2. Religious services at the College must be conducted in accord with Anglican liturgical forms. Should College authorities ever fail to meet either of these conditions, it was made clear by the vestrymen that the land upon which the College sat would revert to Trinity Church. In that half of its members were also Trinity vestrymen, the Lottery Commission could not have been taken by surprise by the new conditions. A majority promptly voted to accept both, with only Livingston arguing against them as effectively creating “a College of Trinity Church.” Taking no public notice of Livingston’s “Twenty Unanswerable Questions,” the Commissioners incorporated both conditions into the draft charter for the college being prepared by attorneys and Trinity Churchmen John Chambers and Joseph Murray, in consultation with President-elect Johnson and the favorably disposed Acting Governor James DeLancey. Although Livingston was still far from beaten, the momentum behind the college was now such that he could not stop its opening. On May 31, an “Advertisement for the College of New York,” signed by Samuel Johnson, appeared in the New York Gazette. After setting out the admission requirements and proposed curriculum “for the intended Seminary or College of New York,” Johnson proceeded directly to assure non-Anglican parents of prospective students that “there is no intention to impose on the scholars, the peculiar tenets of any particular sect of Christians.” Instead, the College would seek “to inculcate upon their tender minds, the great principles of Christianity and morality in which true Christians of each denomination are generally agreed.” Johnson sought to soften the new stipulation as to the use of Anglican prayers in college services by assuring that college prayers would be drawn directly from Holy Scriptures, thereby minimizing denominational offense. And then a final ecumenical reassurance:

The advertisement stated that classes were to commence on July 1, in the vestry room of the new school house adjoining Trinity Church, “till a convenient place may be built.” A half century after Lewis Morris declared “New York a fit place for a Colledge,” New York would finally have one.

From Stand, Columbia by Robert

McCaughey © 2003 Columbia

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||