Ben Ratliff ’90 forms new connections to music while on the move

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

Ben Ratliff ’90 forms new connections to music while on the move

GUS ARONSON

“I found I was listening better than I ever had; I was able to access the inside of the music in a way I wasn’t normally able to,” he says. “I didn’t understand the connection to running, so I thought: ‘I’ll just have to start writing about it.’ I wanted to somehow describe the music I was listening to, but also explain the path that I had just taken and the physical experience I had had.”

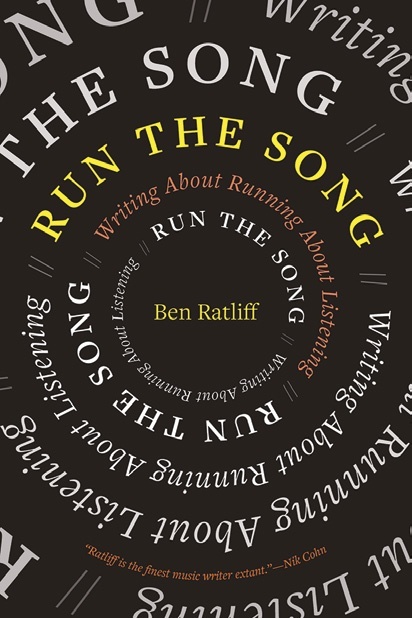

The result, Run the Song: Writing About Running About Listening (Graywolf Press, $18), describes how running — significantly, during an unusual and unsettling time in the world — allowed Ratliff to think and write differently about music. On the move, encountering newly erected fences for an intended FEMA field hospital and demonstrations against racial violence, Ratliff became open to “rerouting his concentration,” and ultimately connected to his area of expertise in a new way.

“Music has motion ... for me, it almost is motion,” he writes. “Running amplifies the motion in music. It took me a long time to understand this.”

Ratliff ’s encyclopedic musical knowledge (he was a substitute DJ at WKCR before becoming the station’s program director) allows for a sweeping range of reflections. He makes associations between disparate artists like Jimi Hendrix and Indian singer M.S. Subbulakshmi, based on “their alertness in bending notes as they move forward,” as he’s moving forward with them. Running through Yonkers, he considers its famous residents Ella Fitzgerald and DMX: “[T]hey knew the same land, the same topography and weather and wind.”

Ratliff acknowledges that Run the Song is a departure in style for him — a kind of meditative writing he says he wouldn’t have been able to do in his professional life as a critic. “I wrote a lot of it in a huge burst,” he says. “But then the quality changed, became more serious and a little less chaotic, once I realized what this book was going to be.”

What it is not, Ratliff clarifies, is a “running book.” He doesn’t train or track his speed or distance (“the last thing I want to do is turn this thing I love into data”), nor does he choose songs or playlists based on their pacing. Ironically, Ratliff doesn’t care too much about tempo, as long as there’s enough energy to keep him going. “It was important to discover that you can run to very, very slow music, and that it can be really clarifying,” he says.

Graywolf editor Ethan Nosowsky ’89, whom Ratliff met during his freshman year at the College, helped him keep Run the Song’s beat. “I had written this strange book, and my agent thought of Ethan as a great potential reader,” Ratliff says. It was the first time they collaborated, and Ratliff found the experience to be extremely gratifying. “It’s such a pleasure to be read by someone insightful, who understands the thing you are trying to do,” he says.

In the excerpt below, Ratliff, who also teaches writing and cultural criticism at NYU’s Gallatin School of Individualized Study, considers how running and listening can illuminate each other; on a jog through the North Bronx, he connects the circles he interprets in the strings from Russian composer Sofia Gubaidulina to the oval he’s making around the Jerome Park Reservoir.

Asked how he decides what to play when he’s out, Ratliff says he tries to be spontaneous and enjoys cueing up less familiar tunes. He says not knowing how long a song will last or how it will end mirrors the state of mind he likes to embody as a runner. “I never have a fixed route,” he says. “To me, that’s what the promise of running is about. You can make choices as you go along. You can improvise.”

— Jill C. Shomer

So without really thinking about it, I do something analogous to what the music does. I run down a hill into Kingsbridge, greeting the astonishing light, moving toward the light of the high, glassy, clustered chords, and then up a hill, crossing the valley of Broadway and going directly east as far as I can go: 200 feet down to sea level and 200 feet up again. I bump into the Jerome Park Reservoir, which is closed, but you can run around the whole thing on the empty streets, past ballfields and medical tents. A rough and giant circle to the other side, where the schools are, Bronx Science and Lehman College, curving back around on Sedgwick — alternating apartment blocks and free-standing houses with steps up to the front doors. Then back toward our neighborhood, via the Van Cortlandt stadium, where I trace a couple more circles on the track.

As I run, the music I’m listening to presumes a setting, and the setting presumes a music, as if my feet were drawing the music in the physical world. In doing so, I allow the physical world to become more vivid. Running-while-listening through any atmosphere — say, the ten-mile radius around our apartment building in the northwest Bronx — helps me to understand and discern the way that music operates in time and place. Running the Bronx and Yonkers and upper Manhattan has disclosed the city to me as far more than “streets”: it is hills, dales, and curves, canting and terraced rock, marshes, forest, highways, streams, bridges, ripped wire fences, places of worship and burial, blocked paths and invitations to connect interrupted planes. Likewise, running with music has disclosed music to me as more than the givens of notes, style, genres. Running and listening can illuminate each other: you remain aware of your current position, while thinking about where you’re heading and where you’ve been. It could be possible to write about running with the vocabulary of listening, and listening with the vocabulary of running. You might start with the word “track.” The word comes from middle English and middle French, “trek” and “trac.” It meant evidence of motion in the past, like a footprint, but then it came to mean a suggestion for motion in the future — a way forward.

Music has motion. It has other things too, but for me, it almost is motion. No motion, no music. The motion could be expressed through a rhythm, steady or varied, or through the connection of one tone to the next, or as the progression of a single tone into silence, or simply by the way music comes to you, as traveling sound waves moving through the air and the body. Running amplifies the motion in music. It took me a long time to understand this. Running while listening can be somewhat related to singing or playing along to music, but with a particular emphasis on moving, as all music does, as all music must do.

EYEEM MOBILE GMBH / GETTY IMAGES

Music is difficult to write about, for the simple reason that it must always be caught up with. Music moves from here to there; it is running away from us. The fact that it runs away from us is a source of joy but also displeasure: a song can drive you crazy, or beguile you, or perplex you, or threaten you. For this reason, many ignore its motion, and prefer to understand it as if it were a finite historical event, which has to mean something.

Music runs away from us. Gubaidulina’s does, manifestly. Half an hour in, with the third string quartet, I still don’t know where it’s going. The strings are prodding me, coming at me with invisible fingers — the fingers of the musicians, playing the pizzicato first half, gathering into masses and then dispersing. In the fourth string quartet, live strings are set against prerecorded sounds of a ghost quartet bouncing rubber balls against the strings, producing the effect of a quickly retreating echo. The string sounds and the musicians themselves are there and not there. What do we do with this music? We can chase it, but a chase implies that we want to capture it, like a hunter chasing an animal, or want to know where it is going, like an officer chasing a suspect. I’m not sure that’s the best response. We can also run roughly alongside it, allowing for it to move in any direction. We can listen to the song, dance to the song, collect the song, study the song, live by or represent the song. There is also always the option of running the song.

I don’t mean letting the music guide you toward the fantasy that you are a particular musician, as if it were possible to borrow the self of Playboi Carti or Martha Argerich for an hour, though these may be nice fantasies. I am also not talking about accepting the music as encouragement for running at a certain tempo, or for adhering to an exercise program. Most of the small amount of writing I have found about running-and-listening is about kinesiology and optimal physical performance — about music chosen mostly to set a pace, to fulfill a precept about motivation. I mean engaging with the music’s forward patterns, its implications, its potential, its intention, and even its desire.

I see that if I go a little further east next time, I will reach another WPA circle, the Williamsbridge Oval, near Gun Hill Road. I can think of a lot more music with circles in it, too.

I’m aware that by doing what I’m doing, and in this particular case, I may be ignoring the “meaning” of the composer’s music, if Gubaidulina would say that its meaning is something to do with spirituality or the subconscious, though I don’t know exactly what she would say. And whatever I did with the music today was not exactly musicology. But I wonder if I’m getting close to it nevertheless.

Excerpted from Run the Song: Writing About Running About Listening by Ben Ratliff. Copyright © 2025 by Ben Ratliff. Reprinted by permission of Graywolf Press.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu