In honor of its 200th anniversary, we look back at the origins and influence of Columbia’s first alumni organization.

Columbia College | Columbia University in the City of New York

In honor of its 200th anniversary, we look back at the origins and influence of Columbia’s first alumni organization.

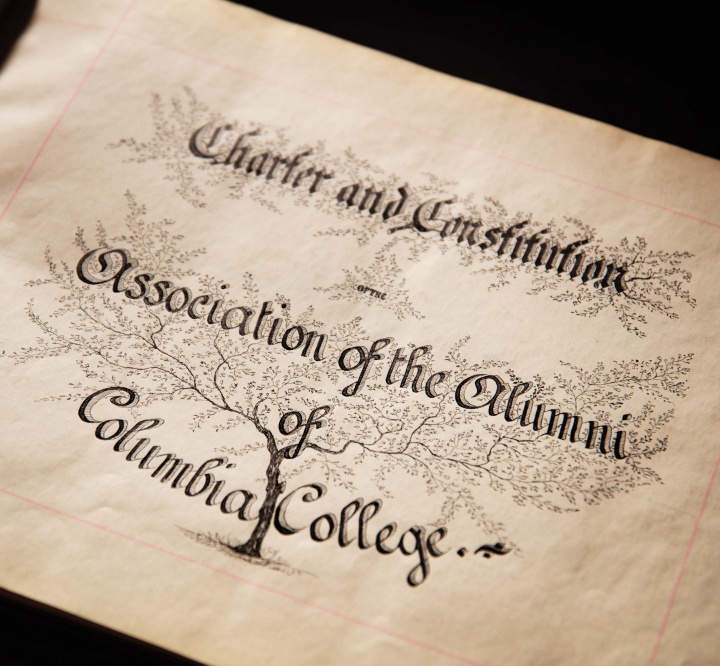

While the CCAA was founded in 1825, nearly 50 years passed before a charter and constitution were officially adopted, on May 21, 1874.

JÖRG MEYER

— Research assistance from Jill C. Shomer, Emily Driehaus and the Columbia University Libraries

Today, having an alumni association feels like a given, of clear benefit both to a school and its graduates. And yet Columbia’s earliest alumni didn’t organize themselves as a collective — at least not officially — until close to 70 years after the first Commencement was held, in 1758. (A class of five perhaps didn’t need such formalities to stay connected.) One early attempt to band together, ambiguously called the Literary Institution, fizzled out in the early 1800s after two years.

Then, on May 4, 1825, a group of College alumni — along with their families, school leaders and faculty — came together to celebrate the anniversary of Columbia’s first Commencement. The festivities included an address by writer and professor Clement Clarke Moore CC 1798. Though he had yet to claim authorship, just a few years prior Moore had penned the poem that eventually brought his greatest fame, “A Visit from St. Nicholas.” (Or as its opening memorably goes, “’Twas the night before Christmas ...”).

Moore’s qualifications to speak that day, however, rested on his College connections. His family played a prominent role in the school’s early history, including his father, Bishop Moore CC 1768, who twice served as its president. Clement was valedictorian of his class, and he became a member of the Board of Trustees in 1813 (a role he held until 1857).

Moore’s address, later published as a book, was given in the College chapel (campus was then located on a three-acre site at Park Place, overlooking the Hudson River). He focused on Columbia history, winding his way through “four distinct periods”: the royal charter in 1754; the Revolutionary War period that saw the suspension of classes; the years marked by oversight of the Regents; and finally, the ascension of the trustees.

The CCAA annual dinner on Feb. 3, 1890, was held at the Hotel Brunswick, then at 225 Fifth Ave.

UNIVERSITY MAGAZINE, COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

He later shifted to a wider perspective, envisioning the association’s usefulness to Columbia: “The reunion of her Alumni at stated periods must tend to produce an esprit du corps in her favour which seems to have been always wanting in this city,” he said. “The name of Alumnus of Columbia College will become a badge of honorable distinction. The welfare, interests, and progress of the institution will be watched over more attentively and by more eyes than heretofore. Its merits and usefulness will become more extensively known, and its deficiencies better understood; its reputation will spread wider, and its improvement be more rapid.”

Moore got a bit philosophical at the end, with a meditation on friendship and the effects of the passage of time. “Whatever tends to draw men together in the bonds of harmony and friendship, is most desirable in this world of jealousy, suspicion, resentment, pride, and coldness,” he said. “The asperities which may have existed among some of our number during our collegiate course, are now obliterated, or felt only as the reminiscences of boyhood; and by these reunions may be converted into friendships. The friendships, too, which existed among fellow-students, and which have since decayed, may here be revived.”

Notably, as The New York Evening Post reported, following Moore’s address “it was proposed and unanimously agreed, that in order to cherish an affectionate remembrance of college days, and to promote a spirit of brotherly good will and kind feelings among the graduates, a book be prepared to receive the signature of every alumnus desirous of joining, as an associate, in the future celebrations of the anniversary.”

And thus, the Columbia College Alumni Association was born.

Roar, Lion, Roar! No Columbia College Alumni Association anniversary celebration would be complete without hearing from the alumni leaders who have kept the community going, and growing, behind the scenes. We asked the most recent CCAA presidents what their priorities were and how they carried out the association’s mission during their term. Here’s how five of them — along with recently inaugurated president Raymond Yu ’89, SEAS’90 — responded:

The CCAA’s mission is to represent the best interests of the College’s various constituencies; during my term, the CCAA carried out its mandate by 1) promoting an atmosphere of partnership and cooperation between the College and Arts & Sciences; 2) increasing participation in the Columbia College Fund and in development more generally; 3) developing a strong working relationship between the CCAA and the nascent Columbia Alumni Association; and 4) supporting intercollegiate athletics (which was in the early years of a rebuilding and strengthening initiative that continues to the present).

— Brian Krisberg ’81, LAW’84; 2006–08

The first half of my term was a tumultuous time at the College. I was the first woman to head the CCAA, with Michele Moody-Adams the first female dean; she resigned during the first month of my term. My earliest official acts were working with Board of Visitors leadership and President Lee C. Bollinger and his staff to install and onboard interim dean James J. Valentini.

At the same time, there was tremendous turnover on the Alumni Affairs staff. Alongside Valentini, my focus was leading the alumni volunteers who were keeping engagement and development programs moving forward as well as increasing the visibility of the CCAA so that our alumni knew they had a voice and representation at Columbia. I also worked closely with Valentini on a strategy for engagement and staffing that was focused on the needs of alumni and students. This included a major reorganization of the CCAA governance structure.

As I reflect on that time and how far the CCAA has come during the last two decades, I am struck by the consistency, dedication and hard work of the board members and particularly the leadership. There is always some level of crisis but as CCAA president you have the support and knowledge of your predecessors and an endless stream of smart, creative and passionate volunteers to tackle the goal of ensuring the best Columbia College possible.

— Kyra Tirana Barry ’87, 2011–14

My primary goal was to improve alumni-student interactions, and to make good on Dean James J. Valentini’s mantra of 100 percent engagement for all alumni. I traveled across the United States and internationally to meet with other alums and encouraged alumni to join class Facebook groups, particularly from classes of neighboring years.

I was also focused on creating a collaborative environment through structured committees and giving the many CCAA volunteers a voice in driving success. During my term, the CCAA helped to launch the Columbia College Women Mentoring Program, which evolved into the Odyssey Mentoring Program in 2017. We continued the work of building alumni presence at Homecoming, and, most excitingly, supported the launch of Core to Commencement, the first fundraising and engagement campaign dedicated exclusively to the College.

— Douglas Wolf ’88, 2014–17

I

Program pages from the dinner commemorating the 150th anniversary of Alexander Hamilton CC 1778’s matriculation.

COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

The Homecoming and Reunions Committee recognized the importance of these two signature events in reconnecting alumni with classmates and with the College. It helped drive improved reunion attendance and programming and expanded Homecoming from a one-day event to multiple days of programming, including festivities on and around campus.

During the 2019–20 academic year, we celebrated the centennial of the Core Curriculum with a series of on-campus and virtual events and programming. We had a gala planned for Spring 2020, which was unfortunately canceled due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

It was an exceptionally productive time for the CCAA and I’m delighted that the initiatives we embarked upon are still flourishing to this day.

— Michael P. Behringer ’89, 2017–20

There was a lot of change both at the CCAA and at Columbia during my time as president. My main focus was reengaging alumni after the lingering challenges of Covid-19, adjusting to new leadership at the College and University, and navigating the campus tensions of 2024.

To support the CCAA’s mission, I worked on two key initiatives. First was a long-term effort to strengthen alumni engagement. One area of focus was to spotlight the remarkable intellectual life at the College. We formed an Intellectual Engagement Committee to bring alumni and faculty together, creating programs that showcase academic content from our incredible faculty.

Another area was tackling concerns from our broad base of alumni about the tensions roiling campus. Our approach started with listening — educating ourselves on the issues, hearing different perspectives and connecting with students. In response, we focused our existing programs like AlumniTALKs, alumni-hosted dinners with students and reunion panels on current University issues. We provided opportunities to learn more about the challenges students were facing and to stay connected with the community.

These efforts were all about keeping the alumni network vibrant, engaged and supportive. Columbia is at its best when we all come together, and I’m proud of the ways we worked to make that happen.

— Sherri Pancer Wolf ’90, 2023–2024

I plan to carry out the CCAA’s mission by enhancing and broadening engagement opportunities that support and strengthen our alumni community as well as the College. We also want to meet our alumni where they are by expanding our programming and events to more geographic locations. Creating more opportunities for alumni to connect with each other and students and keeping them informed about Columbia is vital to our mission.

In partnering with the College and University, we need to ensure we have active, clear and substantive communication with our alumni community. This year is a milestone for the CCAA. We look forward to celebrating our 200th anniversary throughout the year with College alumni from around the world, as we reflect on how Columbia helped to shape our lives and the impact alumni have had on society.

— Raymond Yu ’89, SEAS’90; 2025–

Columbia’s mascot, seen here in 1920, was originally named Leo Columbiae.

Among other things, Compton spoke to the assembled group about pride, and the responsibility held by the alumni association to stoke enthusiasm for the College. “We can never have too much,” he said. “We will put Columbia so far in advance and so high above all similar institutions that no one shall have the temerity to even question her supremacy.” He noted the importance of cherishing old traditions while establishing new ones: “We need more pegs on which to hang the garments of true College spirit.” And he conjured the rival representatives of other schools, already “immortalized in song and story” — Michigan’s wolverine, Princeton’s tiger, Yale’s bulldog.

Finally, with theatrical flourish, he came to his pitch: “In the Pleistocene age an animal, huge in size and without a worthy rival, roamed over England, the ‘King of Beasts.’ He has been called the most splendid combination in nature of majestic beauty with surpassing strength. His voice is peculiarly striking and impressive; loud, deep-toned, solemn.

“Do you not now hear roars from his lair on Morningside reverberating and reechoing among the Palisades, just beyond the ‘lordly Hudson’? What better symbol than this to express our lofty conceptions of the nobility and royalty of Columbia? What better tinder to fire our enthusiasm? Might he not again and again inspire lyric strains, enthusiastic and lofty? Might not such a mascot herald abroad Columbia’s fame in song, and in a thousand different ways? ...

“As ‘God save the King’ gave way to ‘Hail Columbia’ let the ‘Lion of England’ yield to the ‘Lion of Columbia.’ We have the king’s crown, let us have the lion.”

Compton’s motion passed, and he and CCAA president James Duane Livingston CC 1880 subsequently presented a banner bearing the leonine emblem to the Columbia Collection. He was dubbed Leo Columbiae.

Columbia’s students were not so quick to embrace the idea; the matter was debated for several weeks, spilling into the pages of Spectator and other publications. Some thought the lion was too closely tied to British imperialism. Others suggested an eagle, while another group lobbied for choosing Matilda the Harlem Goat. (Legend has it that Matilda, who resided with her owner at a small home on the corner of 120th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, was loaned to students for pranks.) Spectator soon threw up its hands, announcing in its April 22, 1910, issue that “no more space in its columns can be devoted to this subject.”

On May 4, 1910, the Student Board put an end to the controversy and voted to make the lion the official mascot. Compton later received a Columbia Alumni Medal for his seminal contribution. Meanwhile, the lion’s current incarnation, the affable Roar-ee, was introduced in 2005.

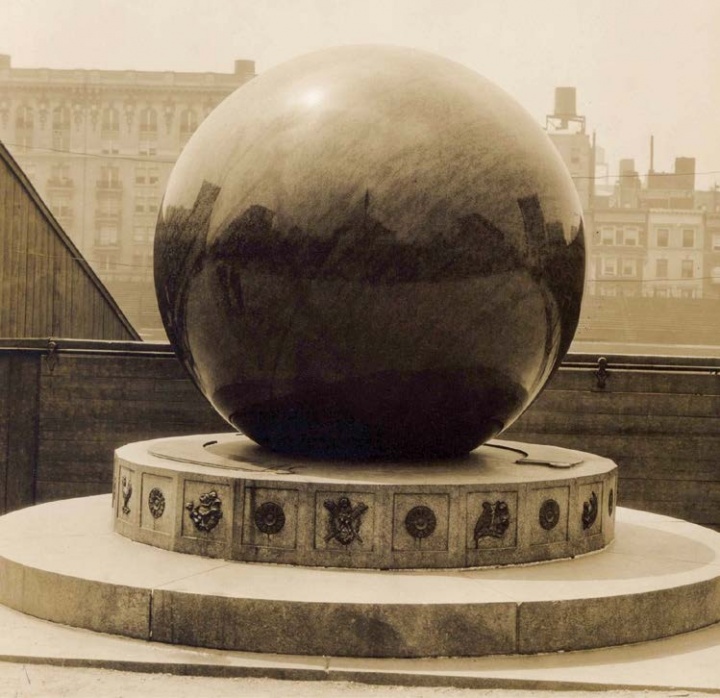

The Sundial was originally functional thanks to the 16-ton green granite sphere that sat atop the base.

So it was that the Class of 1885 decided it would mark the 25th anniversary of its graduation with a monumental contribution: a 16-ton spherical sundial.

Columbia master planners McKim, Mead & White designed the landmark — a nine-foot circular base atop which sat a massive granite “sunball,” nearly seven feet in diameter. But the class’ own Harold Jacoby CC 1885, the Rutherford Professor of Astronomy, played a crucial role in its conception. Jacoby made the calculations that allowed the sphere to act as a gnomon, the part of a sundial that casts a shadow to tell time. (Notably, he also helped map the stars and constellations in the design of Grand Central Terminal’s vaulted ceiling.)

Jacoby calibrated the gnomon to align with Eastern Standard Time. It cast its shadow onto two bronze plates indicating the month and day of the year, hitting its mark at noon each day. Jacoby believed the sundial would have “distinct educational value,” he told Columbia Alumni News in 1910, and he imagined students gathering routinely at midday and wondering at the precision of its workings. It was never off by more than a fraction of a minute.

Meanwhile, sculptor William Ordway Partridge was commissioned to create the brass plates that encircled the base. Partridge had attended Columbia and would have graduated with the Class of 1885 had he not withdrawn for health reasons. He was one of the University’s go-to artists of the time; he created the bronze statues of Alexander Hamilton CC 1778 outside Hamilton Hall and Thomas Jefferson outside the Journalism School, as well as the bust of John Howard Van Amringe CC 1860 that anchors the Van Am Quad.

Partridge dreamed up 12 icons representing the cycles of the day, with fanciful names such as “Torches of the Morning,” “Chanticleer” and “Love Tempers the Night Wind.” An inscription on the base reads “Horam Expecta Veniet” (“Await the hour; it will come).

The completed Sundial was installed in 1914, four years later than the class’ anniversary goal. Butler Library had not yet been built, and so in its early years the monument sat adjacent to what was then the football field.

In 1933 the sphere began to show fissures, and by 1944 a large crack had developed. Attempts were made to slow the damage, but the sphere was ultimately removed in 1946. Jacoby’s vision of the Sundial as a gathering place, however, has lived on.

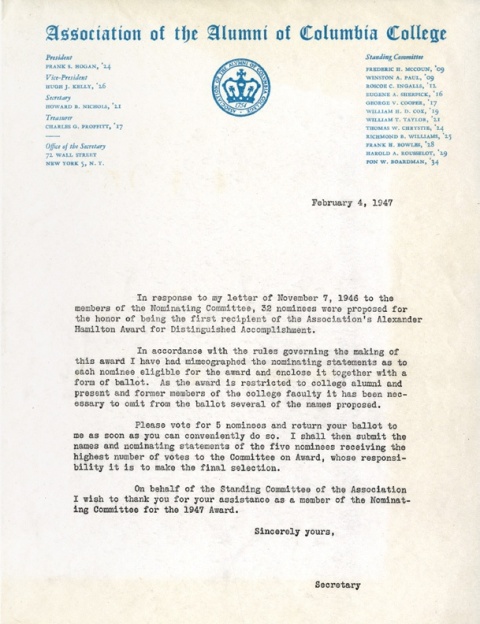

A letter, dated Feb. 4, 1947, outlining the voting process for the first Alexander Hamilton Award.

COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

In fact, the CCAA had already celebrated Hamilton in 1924, with a dinner marking the 150th anniversary of the Founding Father’s matriculation (vaudevillian Will Rogers supplied the entertainment). The honored guest was Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon, who was hailed as a second Hamilton but was not, however, a College alum. Two decades later, CCAA members wanted to enlist Hamilton’s name to pay tribute to their own.

A special committee carefully crafted the award guidelines, including that eligibility be extended to any living alumnus of the College or to present or former members of the faculty. The guidelines also specified the design of the medal itself — it was to be made of Tiffany bronze, with a bust of Hamilton on one side and a reproduction of Low Library on the other.

Thirty-two nominees were put forward for the first Hamilton honor, given in 1947. They hailed from wildly disparate fields, including lyricist Oscar Hammerstein II CC 1916; William Joseph Donovan CC 1905, LAW 1908, the head of the Office of Strategic Services (predecessor to the CIA); publisher Alfred Knopf CC 1912; Chinese politician and diplomat V.K. Wellington Koo CC 1909, GSAS 1912; New York Times titan Arthur Hays Sulzberger CC 1913; and biochemist John Howard Northrop GSAS 1915, who had recently won a Nobel Prize.

The overwhelming choice, however, was Nicholas Murray Butler CC 1882. As University president from 1902 to 1945 — the longest-serving president in Columbia history — Butler was widely recognized as having elevated Columbia to a position among the world’s leading institutions for higher education and research. Among his many accomplishments, he oversaw the creation of the Journalism School, the Business School and the School of Dentistry; doubled the size of campus; and significantly increased enrollment. The Core Curriculum was also established during his tenure.

Butler received the award in a ceremony at his home on June 9, 1947. Frank Hogan CC 1924, LAW 1928, the New York district attorney who was then president of the CCAA, called him a “master architect of American education who has made a lasting contribution to American ideals.”

Butler died later that year. His successor, acting president Frank D. Fackenthal CC 1906, became the second Hamilton medal recipient, and the first to be honored with a formal dinner, in January 1948.

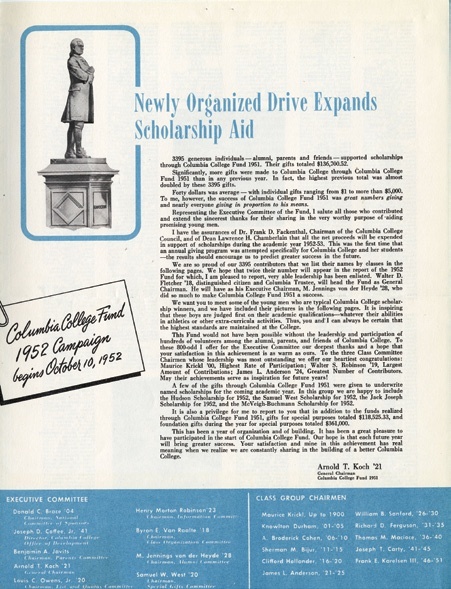

A Columbia College Fund pamphlet celebrated the results of 1951’s inaugural drive.

Thus was declared the objective for a new annual giving program, the Columbia College Fund, in a solicitation letter sent to alumni in 1951. It was the first time that such an effort had been attempted specifically for the College and its students.

Credit for initiating the fund goes largely to Joseph D. Coffee Jr. ’41, the College’s director of development — or “Mr. Alumni Affairs,” as he came to be known — working in conjunction with Dean Lawrence Chamberlain. (The Columbia College Council, an advisory board to the president and trustees, also had a role.) News of its launch, meanwhile, made The New York Times that September. Arnold T. Koch CC 1921, LAW 1923 was named general chairman, with a goal of raising $240,000 by the end of the calendar year; the number represented 400 tuition scholarships at $600 each.

“The scholarship program of Columbia College is a vital part of the College’s fundamental philosophy,” Koch said in the Times. “It enables the College to achieve a representative cross-section of young America in its student body and is a sizable contribution to the present nation-wide need of increased scholarship aid.”

The 1951 letter, arriving on elegant letterhead in Columbia’s traditional blue, opened with some “hard facts.” It noted that the percentage of College alumni who participated in giving was then 10 percent, compared with 63 percent participation at Dartmouth, 54 percent at Yale and 50 percent at Princeton. (“Quite a jolt, isn’t it, to see Columbia at the bottom of its league!”)

Alumni involvement was extensive, as nearly every class from 1895 to 1951 had its own chairman or co-chairmen to marshal classmate giving. In the end, the drive raised nearly $137,000, with 3,395 alumni, parents and friends making contributions, nearly double the number of donors who had given to the College in any previous year.

In a pamphlet sharing the results of the inaugural campaign, Koch wrote a salutatory letter highlighting its successes, in addition to naming the leaders who made it possible. He concluded: “This has been a year of organization and of building. It has been a great pleasure to have participated in the start of [the] Columbia College Fund. Our hope is that each future year will bring greater success. Your satisfaction and mine in this achievement has real meaning when we realize we are constantly sharing in the building of a better Columbia College.”

A view of the Gates from 1968; they had been installed the previous year.

MANNY WARMAN / COURTESY COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY ARCHIVES

In the 1960s, Dell Publishing founder George Delacorte CC 1913 donated $89,000 to construct ornamental gates at either end of College Walk. The pathway through the center of campus, once a trafficked city street, had been left open to Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue when it was added as part of a bicentennial makeover in 1954.

At that time, Delacorte was well on his way to establishing himself as a philanthropist who was more interested in beautification and cultural advancement than in sitting on the board of a museum or hospital. Central Park alone became home to three of his most notable contributions. The Alice in Wonderland statue immediately drew the attention of climbing children when it was unveiled in 1959. Three years later, The Delacorte Theater started hosting free Shakespeare performances. And the Delacorte Clock, encircled by its ensemble of animal musicians, began chiming outside the Central Park Zoo in 1965. (As The New York Times later observed, for Delacorte, adorning the city was a dream come true.)

The Broadway set of gates was completed in 1967; there had been delays due to an ironworkers’ strike, and the dedication ceremony wasn’t held until 1971. Notably, the design for the entryway incorporated an earlier set of alumni gifts: the graceful pylons representing Letters and Science. The former was a gift from the Class of 1890; the latter, from the Class of 1900.

As iconic as those gates — now the capital-G Gates — have become, they were not entirely well received. Spectator pulled no punches, describing them in a December 1967 editorial as ugly and offensive. “Their appearance is undeniably hostile,” the editors wrote. “The last thing Columbia needs is more walls, more fences, more barricades.”

Thankfully the mood changed, and the Gates are now considered synonymous with Columbia. As is Delacorte: Among other contributions to alma mater, he established the Delacorte Professorship in the Humanities and founded the George T. Delacorte Center for Magazine Journalism. For College students, his name might resonate for a different reason, inscribed as it is above the lion’s head fountain outside Hamilton Hall.

Published three times a year by Columbia College for alumni, students, faculty, parents and friends.

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 6th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7852

cct@columbia.edu

Columbia Alumni Center

622 W. 113th St., MC 4530, 4th Fl.

New York, NY 10025

212-851-7488

ccalumni@columbia.edu